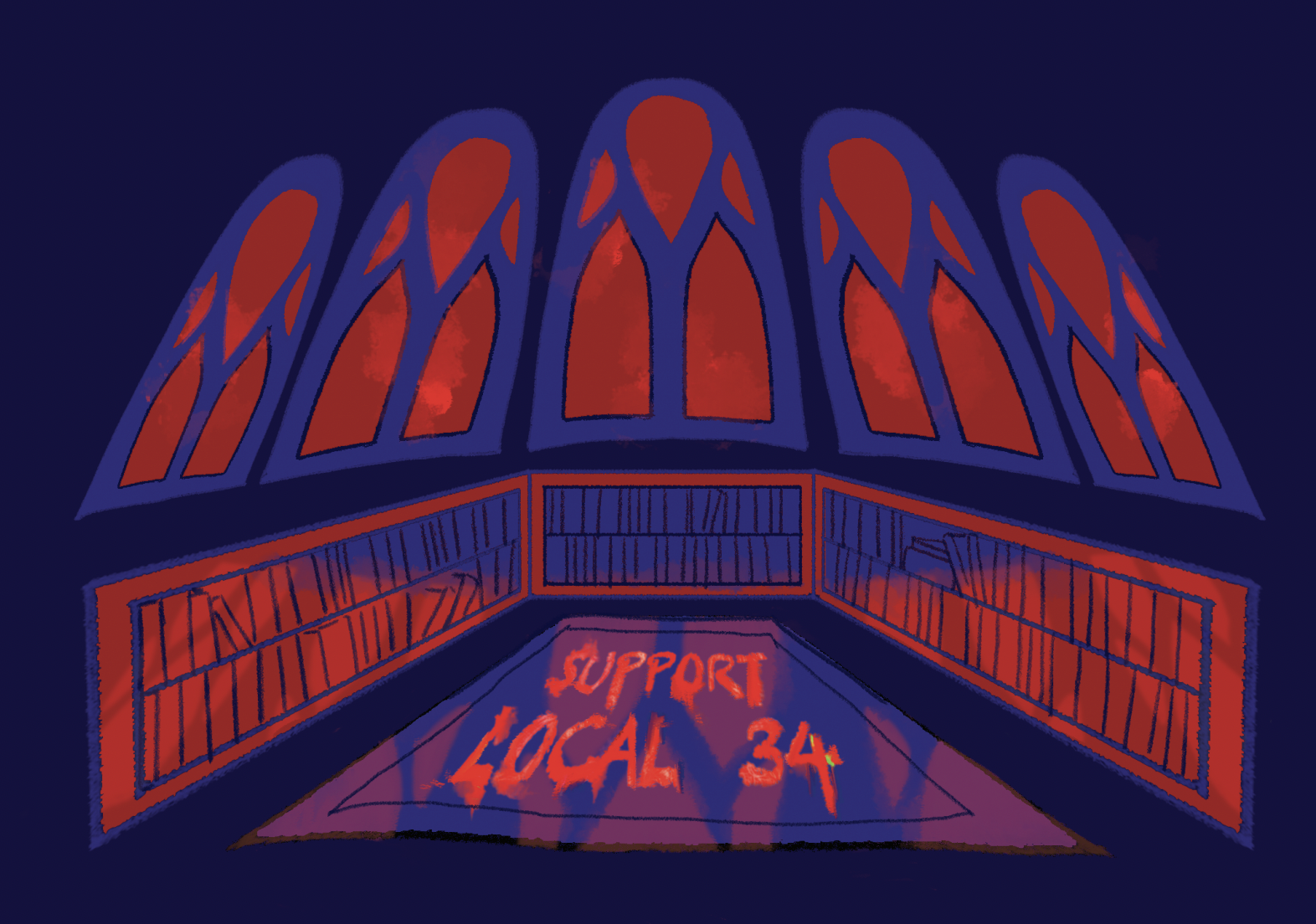

On October 4th, 1984, a group of Yale students carried cans full of paint into the Lillian Goldman Law Library. Some hands grabbed boxes of catalog cards. They dusted the floor with delicate slips, dropping hundreds of hours of work—in paper catalogs—onto the ground. They painted “Support Local 34” in massive letters in red across the center of the reading room carpet. More notes in support of Local 34 defaced sections of the floor. Smaller messages littered carrels throughout the building. “Shut it down,” the wooden walls decried. The protestors left one catalog card propped up in the center of the library. It implored Yale to accept the worker’s binding arbitration. They left the building before any workers entered, leaving the door locked behind them. The vandals were not caught.

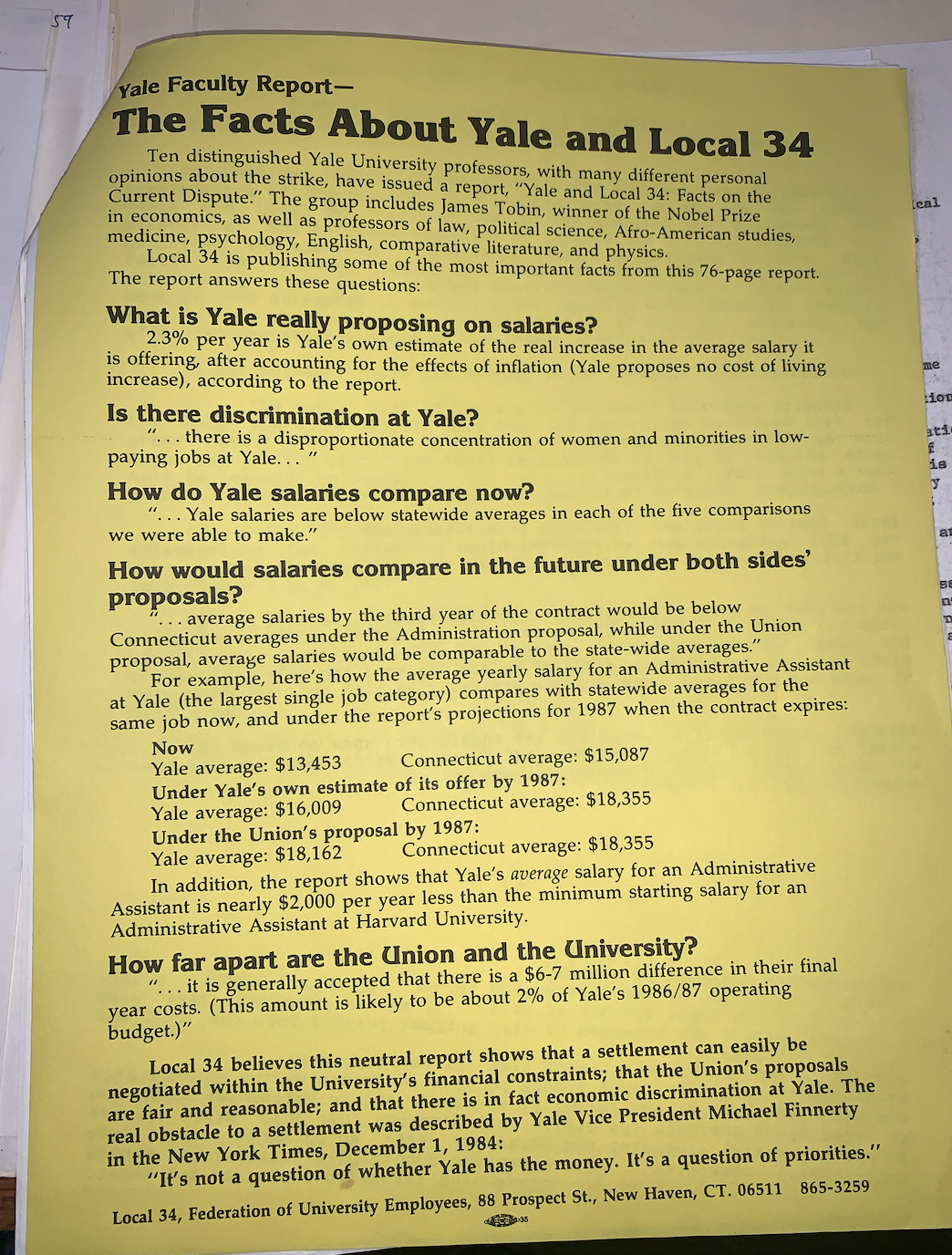

For months prior to the incident, tension had been mounting throughout Yale’s campus. In response to being significantly underpaid, a cohort of clerical and technical Yale employees, which were 82 percent female at the time, unionized and formed Local 34 with support from Local 35. Protests followed, culminating in more than five thousand people demanding that Yale meet the workers’ demands. Subsequent teach-ins, faculty reports, and worker testimonials shed light on the discrimination occurring. Despite these protests and the flood of information, Yale remained steadfast in meager compromises, insisting that they were paying staff fairly. They maintained vague policies regarding free speech. Police shut down nonviolent protests despite them conforming to policies, and some professors harassed students, with one writing to a protesting student that other faculty members were “out for his scalp.” Yale stood behind those who shut down transgressions. Workers went on strike throughout October and November of 1984. Picket lines blocked off buildings and classes moved into off-campus locations like the Grove Street Cemetery.

In the battle against student and administrative apathy, the vandals chose an emotive outburst as their weapon. They transgressed authority—in this instance, Yale—by harming its property. Maria Jose Hierro, a professor of political science at Yale, says that vandalism, when linked to protest, “relates to emotions, to anger, to frustration, to some form or feeling that is the outcome of a grievance…it calls the attention of the authority but it’s about the individual’s expression.” Perhaps the vandals felt their voices and faces were not enough. They needed a faceless, bright red, and massive expression, one that explicitly defies the authority, to demand their acknowledgment. They expressed themselves in a way that cannot be ignored.

And they weren’t alone. Yale’s history of vandalism adorns each social movement. With each major twentieth century protest—the Black Panthers, anti-Apartheid in South Africa, anti-Gulf War intervention—came a slew of shattered glass, graffitied walls, and broken doors.

This act of vandalism in 1984 contained an attempt at strategy. A member of the group anonymously called reporters of the Yale Daily News. She claimed that Yale was oblivious to students bearing the brunt of the strike, stating that she was tired of having classes in a graveyard and “wanted to bring it close to home to end student apathy.” She explicitly distanced the vandals’ actions as separate from the Union and the University.

The Union, writing to the News in response, claimed that such tactics only harmed their movement. Another student in the News wrote that such actions were cowardly because they hid themselves behind anonymity, not allowing for conversational responses. Allies—including the very Union itself—criticized the medium of the transgression, with little regard for its message, in response to vandalism. Attention heeded, but conversations shut down.

Vandalism often incurs controversy, allowing for others to criticize the movement due to its destruction rather than the message of the movement itself. For Hierro, the strategic calculus of vandalism seldom justifies it. “One wants to disrupt authority without thinking about the consequences of those actions and how those consequences distort your message,” she says. “You get a lot of pushback from potential allies or the authority.”

The consequences of these actions go further than disagreeability. In a News report, a Law Librarian, Morris Cohen, remarked that the main individuals affected by the actions were those that had to clean it up. Though property damage may appear to disrupt the authority that manages it, those who steward the property are often more affected than the superseding authority.

***

But what if vandalism’s transgression is creative instead of destructive? Here we encounter graffiti, where the defiance of authority becomes the basis of community.

Kevin Repp, the curator of the Beinecke’s current exhibit—“Art, Protest, and the Archives”—talks through several of these examples. “Art,” he says, “can sit on the edge of violence.” He tells me this as we sit between cases with Dadaist works that gesture to the horrors of World War I and photos of the Sioux art tent pipeline protests in South Dakota. In each instance, people were bound by the art they formed. He tells me that certain artistic communities, brought together through creation, retain their energy by implicit transgression. To him, art’s transgression either unfolds through straightforward messages or by directing the viewer’s emotions against reason using shock. In each instance, art challenges an authority’s narrative, either by questioning or offering a counternarrative. By maintaining this challenge, art edges on violence. And, centered around the edge where art subsists, people come together.

Graffiti can tie people together through transgressive narratives just as art does. Hierro recalls a summer she spent teaching in Barcelona where student organizations painted murals advocating for socialism, independence, and women’s rights. “To me, those were very artistic, and they were art—in the sense that they were trying to leave an imprint, in the walls of their university, of their ideals.”

In other instances, people call for empathy through art. She tells me about graffiti on walls in Mexico and in Palestine. “Why are they in English?” she asks. “Because they are seeking the solidarity of people in other places in the world.” Uniting around the defiance of a common authority, graffiti can combine art’s coalescing power with vandalism’s transgression to sustain a community.

***

The frustration with Yale as an authority, both in dictating permissible expression and in determining institutional action, remains. Yet Yale’s campus remains mostly pristine. In the last decade, the only publicized acts of property damage have been hate speech graffitied onto overlooked public spaces. Why are these the most visible afterlives of vandalism? What’s changed?

An initial explanation is that Yale focuses more on its community than ever before. Joey Adcock, an area manager for the campus, pulls out a graffiti-removal spray can from his desk drawer as he describes this shift. “I’ve wanted service staff to be seen, to show we take care of the place, that we care enough to be out in public and be a resource for those around us,” he says, “and as a result, custodial staff are more respected.” The consideration for those who are harmed by property damage seems to have landed with some students. Adriana Colón Adorno, an alumna who organized with the Environmental Justice Coalition during her years as a student, told me that “vandalism just wasn’t at the top of our minds because we thought there were other things we could do that were based more on building community.”

Another explanation is that incessant surveillance prevents property damage. Police presence at Yale has evolved beyond bodies. Property itself can see, too, with cameras watching students everywhere at all times. As Adcock explains it, there are more eyes watching, with cameras at every corner, and more mechanisms for faceless expression. The internet now platforms countless anonymous voices. He leans back in his chair, saying, “Anonymity is huge. It’s a lot easier for people to just open up a laptop, open up the phone, and, and put out what they want. It takes a lot more time, thought, and effort to put a message out in writing.” The internet’s anonymity grows even more attractive when one realizes that nearly every physical place is monitored, with skilled investigators prepared to track down culprits. Vandalism has lost its anonymity, while the internet makes anonymous expression far easier than ever before.

And even when students move to touch things without the intent to destroy, surveillance pounces on them. “Vandalism” has become a term Yale uses to antagonize disagreeable movements. The Native and Indigenous Student Association at Yale—Yale’s oldest and largest organization of Indigenous students—held a vigil for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women in 2022. Hands, stamped with easily-washable red Crayola paint, covered the walls of Cross Campus in memory of these missing women. The activists both communicated their actions to Yale Facilities and planned to clean after themselves. Administrators messaged the organizers to immediately remove all displays. They strove to, but risked frostbite. A few displays were left to be cleaned the next morning. Organizers found themselves subject to more hostility—cleaned walls and responsible names demanded by administrators.

Later in the year, a pterodactyl, taken from Indigenous land by Yale professor O.C. Marsh in the nineteenth century and immortalized in a glass display case, found its shelter covered in small red sticky notes which read “STOLEN.” These actions were easily removable forms of protest which did not significantly disrupt campus life. Sticky notes are sticky notes, easily removable and nondestructive, especially when on a glass display case. The Yale Police Department identified the Native student protesters by their shirts and IDs, calling them to declare their acts as vandalism. The accusation was, evidently, not about the method of protest, which was harmless. It was about its agreeability with the institution, an institution that could so easily frame certain actions as vandalism.

Today, the incidents of vandalism that leak into this campus appear to be done by outsiders. In the last decade, the only major reported instances of vandalism have been three acts of antisemitic hate speech. In each case, the Yale Police successfully identified the responsible culprits—the identified culprits were juveniles outside of the Yale community. They happened in less visible places than the other acts of vandalism—a bathroom stall, an entryway door, the Law School steps. But these acts were possible only to those outside of the Yale community, those unable to be tracked by shirts and IDs. They act without fear of an institution that they don’t have to answer to.

It remains an open question as to when vandalism will return to campus in the activist vein it once existed. Security camera screens, with their timestamps ticking away, may be the first to let us know.

-Tashroom Ahsan is a sophomore in Davenport College and a Design Editor of The New Journal.

Illustrations by Angela Huo.