On a cold February afternoon, ten people scatter among identical rows of chairs in the basement of the New Haven Free Public Library (NHFPL). Between the patterned surfaces, diffusely lit by the overhead fluorescents, the room hums with noise. It is an hour and a half before the opening day of the Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) site, which operates as a branch of the Internal Revenue Service’s national VITA program. Here, at Connecticut’s largest VITA site, Yale students run the operation.

Thirty minutes before the site officially opens, Yale student volunteers wander in. With widened eyes, they scan the waiting area for their fellow students, now full of clients. Last year, the site brought more than two million dollars back to New Haven and helped more than a thousand people file for free.

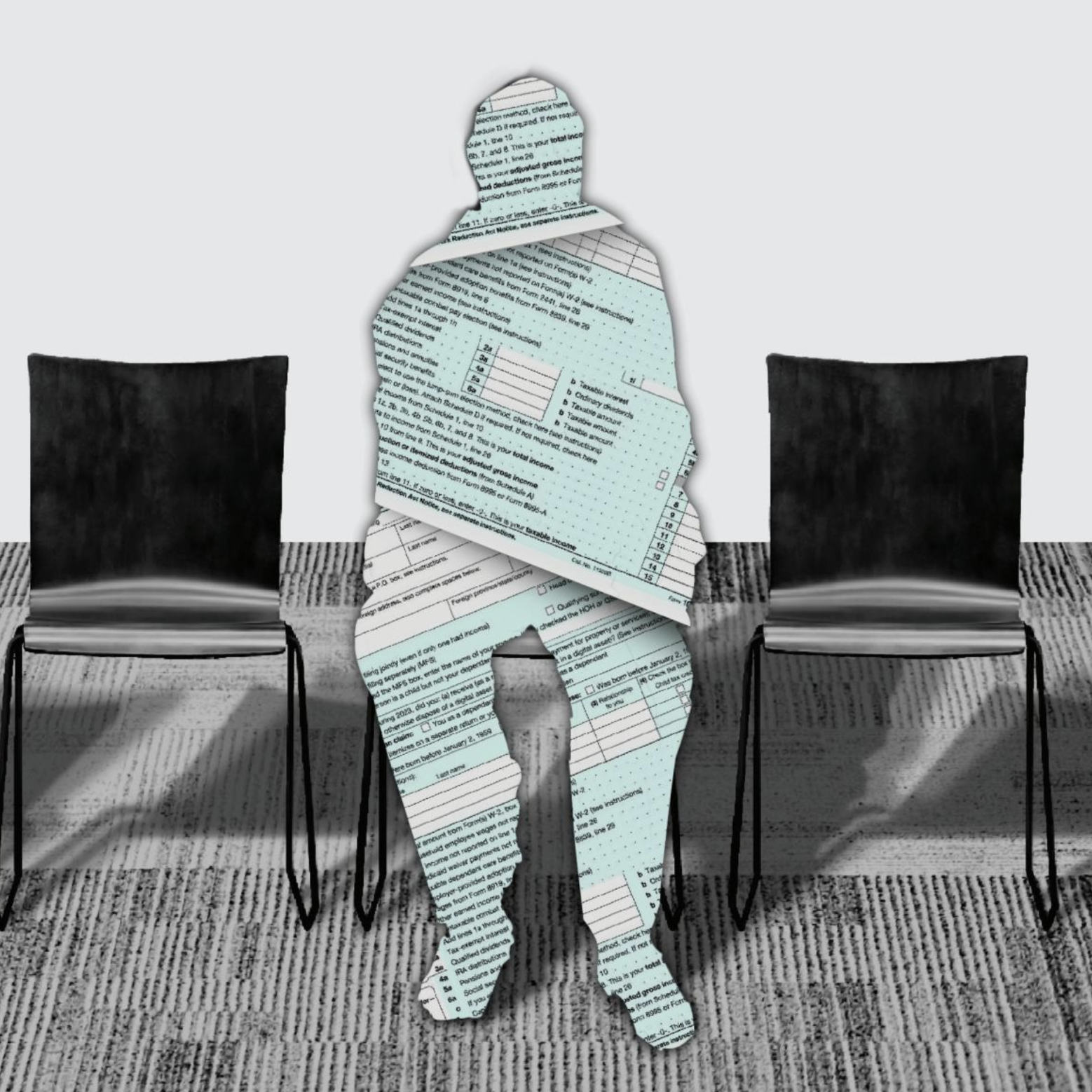

While helping taxpayers avoid costly tax preparation fees, VITA sites also aim to increase access to tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Child Tax Credit (CTC). These credits are part of the complicated web of programs that define the United States’ social welfare system. However, claiming them is difficult for those without a professional accountant or online tax preparation services. Out of the one hundred and forty eight million individual tax returns filed in 2020, only a little more than four million were filed for free. Without the time or energy to parse through the code by hand, the most economically disadvantaged people—including those who do not speak English—bear this bureaucratic and administrative burden the most. As a result, these social benefits often do not reach those who need it. Many New Haveners stand to benefit tremendously from the money these credits put back in their pockets. According to Census data, 21 percent of New Haven residents live under the federal poverty line.

Every year, around 20 to 25 percent of Connecticut residents eligible for the EITC do not claim it, according to IRS estimates. Additionally, an estimated two-thirds of those who miss out on significant EITC returns nationwide are those who choose not to file because they are below the income threshold that requires them to submit a tax return. In Connecticut, the average EITC return was $2,294 for the 2022 tax year, a significant boost for taxpayers. Reporting by Annie Lowrey in The Atlantic argues that these tax credits mirror a larger trend in social welfare: benefits are shrouded in a sprawling, dysfunctional, and complex web of programs that obscures access for those who need them the most. People who do attempt to claim these benefits face time-consuming bureaucracies, invasions of privacy, and the stigma that surrounds social welfare.

VITA serves as a strange band-aid to these gaps, tasking volunteers with the intimate business of interacting with clients one-on-one and handling their Social Security cards, government IDs, and financial documents. On Yale’s site, the impersonal bureaucratic system becomes personal, at once highlighting the people behind the tax code and the barriers to access of the current system.

An Inequitable System

When I spoke to John DeStefano Jr., Mayor of New Haven from 1994 to 2014, he framed the VITA program as a matter of civic duty, for both the volunteer and the taxpayer. Volunteers give back to their neighbors “in a very traditional social contract sort of way,” while taxpayers contribute through their tax dollars. DeStefano emphasized that this definition of citizenship includes undocumented people, who can pay taxes through the acquisition of a Tax ID number and utilize VITA sites to help them file.

When I asked DeStefano about the barriers people face to filing taxes, he remarked, “I think that some things are complicated,” acknowledging that language differences can exacerbate these challenges. However, he equated filing taxes to getting your driver’s license or passing a driver’s test. “I really don’t think that’s too big of a burden to expect of people,” DeStefano said.

VITA leadership repeatedly told me that a significant challenge they face in providing effective service is language barriers. According to Census data, 20 percent of people speak Spanish in New Haven, including those who may be bilingual. Co-President Wendy Zhang ’25 acknowledged difficulties in recruiting enough Spanish-speaking preparers, challenging VITA’s ability to provide the accessible services they aspire to. The Yale student volunteers and clients were separated by another dynamic: race. Census data estimates that 30 percent of New Haven residents identify as Black or African American, compared to 7 percent of non-international students at Yale.

Historically, government social safety net programs have excluded Black Americans, through both explicit and implicit means. This form of structural racism has hindered Black people from building generational wealth. Despite this historical context, Black Americans are pigeonholed into harmful stereotypes like the “Welfare Queen,” popularized by Reagan in the nineteen-seventies, that depict them as the primary beneficiaries of social welfare, leeching off of hard-working taxpayers. These racist characterizations rest on the American ideal of “pulling yourself up by your bootstraps,” shaming those who access social benefits like tax credits.

Outside of the U.S., an estimated thirty-six countries—including Singapore, the U.K., Germany, and Japan—utilize an alternative return-free filing system. The government pre-fills information about an individual’s income into an online portal, prompting the user to confirm or amend the information. On the taxpayer’s end, this takes minutes, compared to the nine hours the average American taxpayer spends filing their taxes every year—according to IRS estimates. Since the U.S. government already receives information about an individual’s income through their employers, it could follow those countries’ leads in instituting an easy filing system, which would reach an estimated 41 percent of the population. This would also eliminate the need for many to visit VITA sites or pay for private tax preparation services.

Since Ronald Reagan, president after president has repeatedly pushed for similar reforms. But the tax preparation industry, which stands to profit tremendously from a complicated and inaccessible tax system, has intensely lobbied against such reforms. In 2003, a coalition of tax prep companies, including the leading company Intuit, entered an agreement with the IRS in which the government agency agreed to stop providing its own online free file system. In exchange, tax preparation companies themselves operated IRS Free File services in partnership with the IRS. These programs make online tax preparation available to income-qualified taxpayers, about 60 percent of the population at the time. But in practice, these private companies deliberately obscured access to Free File portals and deceivingly labeled paid services as “free.” In 2021, Intuit pulled out of IRS Free File and in 2022, only 2 percent of people eligible for Free File took advantage of the program. This year, the IRS is piloting its own online tax preparation software through the Direct File program in twelve states, excluding Connecticut.

Currently, Yale’s VITA program is not pushing political advocacy for tax reforms. When I brought up the idea to VITA Co-President Joanna Wypasek ’24, she speculated that they might be able to implement advocacy in the next fall semester.

“[B]eing from Yale is not a badge of honor in that situation,” Rena Liu ’26, a second-year advanced preparer said, acknowledging the trust required between tax filer and student. Joining out of an interest in contributing to New Haven, Liu shared that her extracurriculars at Yale felt mostly self-serving before the spring semester of her first year when she joined VITA. Many in the city, including organizations like New Haven Rising, argue that Yale does not pay its fair share in New Haven due to its exemption from property taxes because of its non-profit status. Although Yale has pledged to voluntarily contribute $135 million over the next six years and contributes through other initiatives like New Haven Promise, the city still misses out on $100 million a year. “I feel like almost being at VITA was kind of like a small way in which I could be like, ‘I’m really sorry that I am benefitting massively from a system that hurt you,’” Liu shared.

The Inner Workings

I sat down with Tom Costa, a librarian at the NHFPL who has worked with Yale students on VITA for roughly twenty years. Earlier, I had wandered around the library, observing the extensive resources housed in the building: shared computers, a café, a teen center, and a “Tinker Lab.” Speaking in a slow, measured cadence, Costa explained that the library’s wide array of offerings are in service of the library’s mission “to be an actual community center.” Among these programs is VITA, hosted in the basement next to a popular teen center and a social work office.

“The city sees this as a very important program,” Costa said, emphasizing the continual support of the New Haven Mayor’s office through events like an annual kickoff. “[B]ecause these funds are coming back in sizable refund amounts to the individuals, to the families, and they spend it in the community, thereby boosting small businesses.”

Although around fifteen VITA sites operate in New Haven, Costa said the downtown NHFPL VITA location is the largest in the state of Connecticut, regularly completing the most returns per year.

The downtown NHFPL site disaffiliated from Yale over the pandemic due to university restrictions on in-person operations. However, all of NHFPL’s VITA’s volunteers are Yale students, both undergraduate and graduate. The job demands a high level of responsibility and professionalism from its leadership—other VITA sites often run out of established non-profits, like United Way. Student leaders draw from a deep well of institutional knowledge, working with an extensive list of partnering organizations to make the site function: the NHFPL, Connecticut Association for Human Services (CAHS), Yale Hunger & Homelessness Action Project (YHHAP), and the IRS.

Costa outlined the evolution of the program from its inception in New Haven in the early two-thousands to the present. The site grew steadily in publicity and capacity throughout cycles of Yale student leaders. The COVID-19 pandemic challenged the program, but it has since rebounded, with ninety-eight currently active volunteers. The volunteers I spoke to were motivated to give back to their communities, choosing VITA because of its ability to make a tangible difference in other’s lives.

“The money that people are getting back makes a huge impact,” Co-President Zhang shared.

VITA sends emails to its volunteers every day the site operates, Monday through Saturday, for about nine weeks until Tax Day on April 15. Each email includes a red number—the amount of money that taxpayers owed that day—and a green number, which is always significantly larger and denotes the amount of money that was returned to clients.

VITA volunteers strive to express sensitivity, respect, and understanding, especially when a client finds out they owe money or that their return is not as sizable as they had expected. Zhang recalled instances when she had to explain to people why their returns were smaller than they expected, especially after pandemic-era expansions of the Child Tax Credit expired. This thoughtfulness seemed attuned to navigating the vulnerability required of clients and the responsibility given to volunteers on the VITA site.

Every VITA program abides by the IRS prescribed structure. Clients fill out an intake sheet, bringing their Social Security card, an official form of identification, and all relevant tax documents to the site. The VITA volunteer reviews these materials, inputting data into the online tax preparation system “TaxSlayer,” which automatically calculates the return. Before submission, each return is double-checked by a different volunteer. Filing is often simple, as volunteers are limited in scope and unauthorized to prepare for taxpayers with specific, complicated situations. But volunteers still need to know the right questions to ask. For example, if a volunteer misidentifies the filing status of an individual as “single,” instead of “head of household,” the taxpayer may miss out on certain benefits. Volunteers must understand the basics of tax law and be prepared to explain returns to clients.

The Volunteer Standards of Conduct Agreement, signed by all VITA volunteers, reminds volunteers that “fraudulent returns that report incorrect income, credits, or deductions can result in many years of interaction with the IRS as the taxpayer tries to pay the additional tax plus interest and penalties. This can result in an extreme burden for the taxpayer.”

Training Volunteers

Over the previous fall semester, I watched the five training video modules ranging from twenty minutes to an hour that Yale student VITA leaders created, touching on the fundamentals of tax law.

In January, I walked into a lecture hall for VITA’s “Certification Party,” a gathering to pass the IRS’s official certification exams. Although the exam is taken individually online, organizers talked through exam questions in groups, eventually giving each volunteer the correct answers and officially qualifying all participants to volunteer on an IRS VITA site. The exam guidelines instruct volunteers to take the test individually, noting that “taking the test in groups or with outside assistance is a disservice to the customers you volunteered to help.” However, three out of four of the VITA sites I have interacted with approach the test similarly, in groups with correct answers eventually provided to all volunteers.

Computers out, we gathered in groups according to certification levels, which ranged from “Intake Coordinator” to “Basic Preparer” to “Advanced Preparer.” A veteran VITA volunteer, one of the site coordinators, prompted individuals from my group to read the exam questions aloud while soliciting answers from the group. I strained to hear amongst the echo of the tall, domed ceiling, hushed voices, and the hum of other groups’ discussions. We breezed through the exam. When tougher questions made the group pause, some students opted to switch tabs on their computers to Publication 4012, the official Volunteer Resource Guide. While they searched for official guidance as a volunteer would be expected to do on a VITA site, others sat quietly and waited to be told the correct answer.

When I asked Theo Schiminovich ’25, a new volunteer with VITA, about his level of confidence going into his first session, he paused, choosing his words carefully. “I feel like I’m gonna need to work up to it,” he said. “I’m in the stage right now where I don’t really know what it’s going to look like, so I have this void in my mind.”

Before preparing returns independently, new volunteers shadow experienced ones. Co-President Wypasek described the steps after shadowing as “a gentle push towards doing it on your own.” She added, “we try to also give them the tools so that if they’re stuck, they know what to do next.” Volunteers can search the IRS website or the official Volunteer Resource Guide, ask fellow volunteers questions, and check in with their IRS point-of-contact. In daily emails, leaders share lessons learned and keep a running document of common questions. As new volunteers build their confidence on the job, capacity is limited early on in the tax season. Wypasek alluded to this bottleneck, warning, “the first week might be very very hectic.”

Waiting On Site

On the first day of VITA’s operation, I stood next to Andrea Santiago-Tito SOM ’24. We met in the waiting room; she has used VITA for six years.

“I come here every year because I don’t trust going to other companies and other environments,” Santiago-Tito said. “I feel the Yale students, we have this trust where, they know what they’re doing.”

On the NHFPL flier, the downtown branch is listed plainly among other NHFPL VITA locations and does not advertise its affiliation with Yale students. Sitting among the clients, I noticed how the students seemed like the youngest people on site, with their stickered laptops and backpacks.

Santiago-Tito and I watched the waiting area fill up the middle of the library basement. Earlier, I had witnessed a public argument between a pair of clients who were worried about what order they would be seen in. The library staff and security guards, milling around in reflective layers, diffused the conflict.

“I’m not in a rush to just be first, as long as I get it done,” Santiago-Tito said. I turned my head to the rustling of coats in the waiting area as people stood. Santiago-Tito bolted, securing a space in the rapidly forming line.

Santiago-Tito was number nineteen among twenty-two taxpayers who were taken that day. VITA volunteers are not allowed to stay after the library closes, so they preemptively limit the number of clients they will see in a day. When I asked Costa, the librarian, about the walk-in format of the site, he explained that a format blended between appointments and walk-ins functioned less efficiently, as appointments were often missed, leaving volunteers with nothing to do. Costa told me that volunteers averaged twenty-eight to thirty-three people every three-and-a-half-hour session.

On the last day of the site’s first week, I returned to the waiting area and sat down next to Clevetta, an older woman bundled in her winter coat, hat, and gloves. She told me that she had attempted to come the day before but had been turned away. This time, one of the library security guards was tasked with handing out numbered index cards to denote those who would make the cut for a session.

“It’s comparable to H&R Block, in my book.” Clevetta remarked. “They’re always thorough, always helpful, always introducing themselves, and very knowledgeable.”

I asked her whether she had faced long wait times before. As we spoke, others who were waiting began to notice that the index cards had been given out of order, confusing who was to be seen first. Clevetta responded, “No, I’ve been lucky I suppose, or blessed that when I come it’s…” she paused. “This is the first time I’ve seen this many people.” I chalked the chaos up to first week growing pains. Another woman sat down next to us, joining the conversation. In hushed voices, they exchanged stories of the ways companies like H&R Block and Jackson Hewitt had taken their money, tax season after tax season.

Four hours later, I returned from class to the library and was surprised to see familiar faces, including Clevetta, rearranged into different configurations around the room. The Yale students, meanwhile, were transitioning to their third personnel shift of the day. I sat down next to a pair of women talking, playfully analyzing the volunteers’ actions. I asked them about how long they had been waiting. One responded, “they take their time, that’s why it takes so long and that’s why people get frustrated and get aggravated, but they gonna make sure they do it right.” Between those who were waiting, a friendly camaraderie formed. Small conversation and laughter emerged often, disrupting the long stretches of waiting that characterized the site.

I stood to leave again, wishing them good luck. One man tried to get me to stay and wait for my taxes to be complete. “They’ll get them done for you,” he insisted. I smiled, explaining that I was a student, writing a story about the site. “I knew you had that student look about you” he quipped. I chuckled, waving goodbye.

When I returned to the VITA site for a third time during its second week of operation, the waiting chairs were already filled. All twenty-one numbered index cards had been passed out according to arrival time. The site would not be accepting anyone new that day. As the clients stood, I watched them arrange themselves into a neat line between the stanchions. I wondered if it was like this all tax season: demand high, the atmosphere thick with waiting, and the site at full capacity.

— Ai-Li Hollander is a first-year in Morse College.

Photography by Nithya Guthikonda and Illustration by Cate Roser.