One plot of land in Westville has seen two failed affordable housing projects in the past fifty years, revealing the pitfalls of public housing development in the city.

“It was once a beautiful place to live,” Elizabeth Yarbrough told me when I asked about Westville Manor, her old home. She moved to the affordable housing complex in 1993 to raise her sons, who thrived in the nearby woods and “family-oriented” community. “My house was always open to the kids,” she told me, smiling.

Today, toppled grills and boarded windows line the dead-end streets of the Manor. The concrete units in a remote northwest fringe of New Haven seem more like barracks than the cute townhouses Yarbrough recalled.

Six years ago, the city approved a plan for redevelopment. In preparation for the first phase of demolition in spring of 2020, the housing authority forced residents on the north side of the Manor, including Yarbrough, to relocate. Now, the promise of renewal seems empty—units which were cleared out have new tenants, and the Manor remains untouched, isolated, and in physical decay.

Politicians and developers frequently pledge to build affordable housing. But the path to completed and thriving homes is slow, and subject to greed, bad planning, and discrimination. Westville Manor, and the fifteen acres on which it stands, knows these struggles too well. The land has hosted two failed affordable housing complexes over the course of fifty five years: first, a public housing project by a celebrity architect that promised radical change; next, its disconnected and poorly maintained replacement, Westville Manor. The story of this land illustrates how stigma, mismanagement, and corruption have plagued affordable housing developments in New Haven, upending the lives of residents.

***

Paul Rudolph moved to New Haven in 1958, appointed by Yale to chair the Department of Architecture. During his time at the university, Rudolph developed a keen interest in designing buildings using prefabricated mobile home units. With their low cost and efficient construction, Rudolph believed prefab would be the solution to America’s housing crisis.

When Rudolph arrived in New Haven, Mayor Richard Lee’s urban renewal mega-project was just underway. The two men collaborated on a number of structures during Lee’s tenure, including Temple Street Parking Garage in 1961 and Crawford Manor in 1966, a housing complex for the elderly. In 1968, they began their final project together: Oriental Masonic Gardens, a federally funded housing complex for low-income families constructed of prefabricated units and located on the site of present day Westville Manor. The proposal came on the heels of the race riots in the summer of 1967. For Lee, the development was a chance to improve his relationship with New Haven’s Black community. When it opened, approximately 75 percent of the families living in the Gardens were Black, racially integrating West Rock, a predominantly white neighborhood. Additionally, the experimental use of prefab was a chance for New Haven to again receive national recognition, attention Lee had basked in during urban renewal in the 1950s. The mayor unveiled Rudolph’s sketches in the presence of George Romney, Nixon’s Secretary of Housing and Urban Development, in 1969; much to Lee’s delight, the press closely followed along.

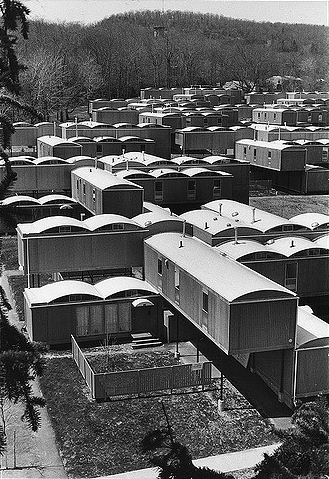

The vast majority of affordable housing complexes at the time were highrises in dense urban areas. The Gardens were much the opposite, consisting of one hundred and forty-eight homes spread across wooded terrain. Each home consisted of two or three modular units made of plywood stacked on top of each other. Unlike most public housing projects, Oriental Masonic Gardens was managed as a non-profit cooperative. Residents could own their units, as opposed to renting them. Rita Reif of The New York Times wrote an overwhelmingly optimistic article, “Thanks to Prefabs, Out of the Slums and Into Their Own Co-Ops,” in February of 1972, six months after the Gardens opened. Reif portrayed happy families and described the complex as “meticulously maintained,” suggesting that the “pride of ownership and sense of community involvement was evident.” Seven years later, the development was slated for demolition.

Oriental Masonic Gardens faced nearly every challenge imaginable. The development was originally budgeted for 3.4 million dollars, but the prefab units were more expensive than anticipated; there was little precedent from which to estimate cost. All told, the Gardens went 450,000 thousand dollars over budget, even as developers cut corners to save money: units sat on concrete posts instead of full foundations; unprotected pipes froze in the winter; one resident described having to hold an umbrella while cooking—roofs didn’t fit units and often leaked. The co-op defaulted on payments in 1978, leaving the project in the hands of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the New Haven Housing Authority.

Despite the negligence in construction, much of the blame for the decay at the Gardens was directed towards the co-op owners, architectural historian Sean Khorsandi explained to me. Articles from the time cast residents derisively as “people who couldn’t take care of things, who were used to living in apartments and weren’t used to maintaining a yard,” Khorsandi said.

Affordable housing was stigmatized even when it was owned and managed by a government agency. In the early 1950s, to appease white Hamden residents, the New Haven Housing Authority helped fund the construction of a fence separating Hamden from West Rock’s housing projects. The oppressive barrier stood in the near vicinity of the Gardens and Manor, a symbol of racial and class animosity that stood until 2014. When Yarbrough lived in the Manor, she described two minute drives to Hamden taking thirty, thanks to the fence. As New Haven Mayor Toni Harp worked to take the wall down, Hamdenites pushed back; one told The New York Times, “We don’t want the thugs on the corner, the cars racing through here.”

By the time demolition of the Gardens was announced in November of 1979, half of the decomposing units had been abandoned; everyone who was able to leave had done so. The remaining sixty families were relocated by the state. Lee and Rudolph had moved on, but the Gardens loomed large in the minds of those who designed its successor.

In December of 1980, the New Haven Housing Authority invited proposals from developers for what would become Westville Manor. They were planning a complex structure nearly identical to the Gardens: 158 units, ranging from two to five bedrooms, spread across the hilly site. The final design called for units built on-site out of concrete blocks, a reaction to Rudolph’s factory-made, plywood failure. Things would be different this time, the developers promised. Ownership of the project was transferred to the New Haven Turnkey Construction Co in November 1984, which hired Kantrow Construction, owned by brothers Michael and Richard Kantrow, to serve as the property’s general contractor.

One month into the project, the Kantrow brothers requested an additional one million dollars from HUD to cover “costs incurred as a result of unknown subsurface soil conditions.” HUD’s Hartford and Boston offices denied the request. The Kantrows, working under a tight budget, kept pushing, and HUD’s national office provided them an extra eight hundred thousand dollars. Westville Manor opened to residents in 1986, but became ensnared in controversy regarding the Kantrows’ request for additional funds. After years of investigation, the brothers were indicted for conspiracy to defraud the federal government. Michael pleaded guilty in 1994. In the words of one HUD employee, the Kantrow case was just the “latest chapter” in Westville Manor’s “long and tortured history.”

***

Despite the corruption, the Kantrow-constructed units were in good condition when Yarbrough arrived in 1993. Fortunes began to change in the Manor in 2006, when the housing authority started redeveloping Brookside Estates and Rockview Apartments, temporarily relocating a number of residents into the Manor and fracturing the tenant community. Four years later, the state shut down West Rock Nursing Home across the street, leading to incessant break-ins, graffiti, and overgrowth on the property. Without the nursing home’s patients and ninety employees coming to work each day, the Manor felt more remote than before, Yarbrough remembers. The Manor homes also started to physically deteriorate. Two children were hospitalized after part of a unit’s ceiling collapsed in 2013, a structural issue that afflicted many of the homes. With physical decay and the presence of temporary residents, “things just went downhill,” Yarbrough explained. In May of 2014, there were four shootings in the Manor in the span of a single week.

By 2018, the project was in a state of “obsolescence,” Shenae Draughn, president of the New Haven Housing Authority, told me. In collaboration with residents and the housing authority, Kenneth Boroson Architects completed a master plan for the redevelopment of Westville Manor in 2019. It is the same local firm who designed Brookside and Rockview, complexes which are seen as incredibly successful. The proposal features two large recreational green spaces, ample but less visible parking, and the creation of three new streets, one of which curves through the entire complex. The design seems promising, cognizant of the site’s former challenges and thoughtful in how it addresses them. While it doesn’t include the screen doors and walled-off gardens that she and her fellow residents lobbied for, Yarbrough agreed it was an improvement.

When Yarbrough and I spoke, we sat in the living room of her new home in Rockview where photos of her sons and grandsons line the walls and her favorite color, bright red, fills the space. Yarbrough immediately made me feel welcome, ushering me inside from the cold even though my shoes were covered with snow. She was one of the residents on the North side of the Manor who the housing authority relocated in preparation for phase one of demolition and construction in 2019. Six years later, there is still no progress on the development.

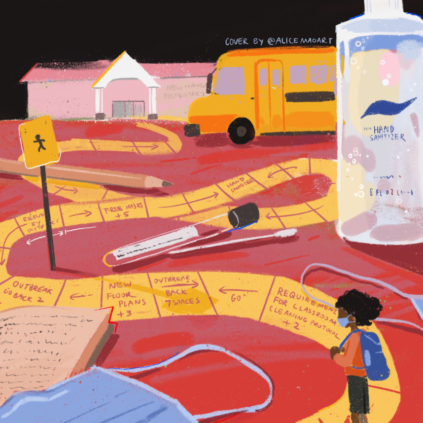

The pandemic arrived before phase one broke ground, beginning a period of inaction that continues today. Getting federal subsidies for constructing and renovating affordable housing is extremely competitive, and the housing authority’s bids have thus far been unsuccessful. Draughn seems optimistic that they will secure the money soon, but it only covers phase one of the project. Relief for residents is many years away.

***

I approached a woman, who requested to use the pseudonym Maria to protect her identity, one frigid January afternoon as she scrubbed the exterior of her white SUV. She told me she had been relocated by the housing authority to the Manor only a couple of months ago. The public housing project which she had long called home, West Hills, is currently undergoing its delayed redevelopment. She had no sense of when demolition at the Manor would begin, when she would again be forced to pack up and move. I asked how she liked living in Westville Manor, and she told me “it’s no different from any other neighborhood, it has its problems, it has its shootings, it needs work done.”

In our conversation, Draughn talked extensively about the stigma surrounding public housing. The fact that the Hamden fence came down only about ten years ago “speaks to this shared bias that continues around what we think about the families who live in affordable housing.” At the same time, a two bedroom unit in New Haven costs close to two thousand and four hundred dollars per month, 35 percent higher than the national average. “Entry level teachers, entry level police officers, they can’t afford to pay that,” Draughn explained.

When a project undergoes redevelopment, the housing authority gives the displaced residents the choice between a unit in another one of their properties or a voucher to buy a home. Each resident also has the option to move back once construction is complete. While she has some fond memories of Westville Manor, Yarbrough is settled and content in Rockview. “I wouldn’t go back,” she told me.

-Elias Theodore is a sophomore in Jonathan Edwards College.

Graphics courtesy of Elias Theodore.