I started taking my clothes off for money when I was eighteen. In my first year of college at Cambridge, I was trying on some personality traits, throwing off others, always to make an impression. I’d march off to sessions with borrowed bathrobes, cheerfully passing friends and letting them know where I was going. I was proud of this new hobby and all that it entailed: my body, my confidence, my difference. From the earliest days to what is now my fifth year of modeling, my frequent nudity hasn’t ceased to be a talking point for others.

In England, where I’m from, people call it ‘life modelling,’ but as a graduate student here at Yale, I’ve discovered that in the US, this term doesn’t carry. Instead, I’ve learned either to grapple with the ambiguous ‘art’ or ‘figure’ model used here, or embrace more loaded terminology. It was a real surprise when a fellow Yale student, not getting my drift, exclaimed, “Oh! You do nude modeling.” To me, nude modeling meant pornography. Yet I reminded myself of the words of the brilliant twentieth-century art historian, writer and broadcaster Kenneth Clark, whose book, The Nude: A Study in Ideal Form, I read in my first term at Cambridge. His bold opening makes this claim: “The word ‘nude’ … carries, in educated usage, no uncomfortable overtone. The vague image it projects into the mind is not of a huddled and defenceless body, but of a balanced, prosperous and confident body.” Clark, however, was concerned with the artistic depiction of human nudity, the alabaster statues and the Raphaels. But when I’m on that pedestal, I may be “nude” to everyone drawing me, but I’m “naked” to myself.

The first time I modeled was a nightmare scenario right out of a Freud reader. As a musician, I had brought along my violin (which I can play) and a borrowed cello (which I cannot). The art class met in Cambridge University’s engineering department, which, as an English student, I’d had no cause to visit before. The vast lecture hall was dark except for two ferocious spotlights. What was a lecturer’s desk by day had been turned for this evening class into my platform. It was far higher than I had been expecting, raised for the display of scientific utensils. But, mustering my courage, I unpacked my instruments, and slipped off to a restroom to undress. I returned in a long scarf wrapped around me—an arrangement that unfortunately did not allow me the casual dropping of a robe from my shoulders. I clambered onto the high platform and paused, feeling my knees lock and my pelvis tighten. The lights were bright and the auditorium cavernous and dark. I could see no one. I felt suddenly, shockingly, undressed, hyper-aware of my nipples, my underarms, my vagina. I could hear the artists’ preparations—paper reams unrolled, leads sharpened—even if I could only catch the luminescent outline of their backlit heads. The soles of my feet were alert to the surface of the bench as I picked up the violin at my feet and began to play.

The music helped. It gave me something to focus on and allowed me to lose track of time. Even so, I never forget that I’m naked and, unsurprisingly, it is those most secret parts of my body that I think about most.

In my experience, the artist’s model is protected by her naked state and the depersonalization of the drawing process. My modeling does have a sexual charge, but it’s mostly inside my own head. The class members will not often know your first name and will never know your last. That kind of identity is superfluous to them. It is rare for a model to be addressed by a member of the class; you can converse afterward, if you like, but invariably you begin the dialogue. At times I have asked for a break just to speak, to have my voice breach the silence of the studio. I have witnessed the class’ attendant shock. When I am naked in this way, no one expects me to have a voice or a personhood; stripped of those qualities, I feel my sex appeal is radically diminished.

Usually I don’t talk. Usually, I stay still. It’s harder work than it looks. Staying still is, paradoxically, a physical activity that involves sweating, muscle fatigue, and a raised heartbeat for the majority of the session. We begin with standing poses, maybe three or four, sometimes with a longer one at the end. Don’t point your toes, don’t lift your hands above your heart for two sequential poses, remember to change the weight from one side of the body to the other between poses. Then we switch to a seated pose, and it’s a relief to get onto the floor. I try to remember the poses I’ve seen other models do, or run through paintings of nudes in my head. Often I spend much of each pose working out the next one. Which limbs do I want to preserve or rest, and which can take the strain? And you know if you’ve made a wrong choice immediately, but it’s usually just a touch too late to change. So your muscles twitch involuntarily. Your inner joints feel physically large, made of flesh and metal, capable of piercing pain. You spend time sucking the pain out of one limb and into another, mentally, imagining the tendons relaxing though they don’t move. You try to ground yourself in your buttocks when your wrist is giving out. You try to stop your trembling thigh by imagining a pole thrust into the floor from your heel downward, for stability.

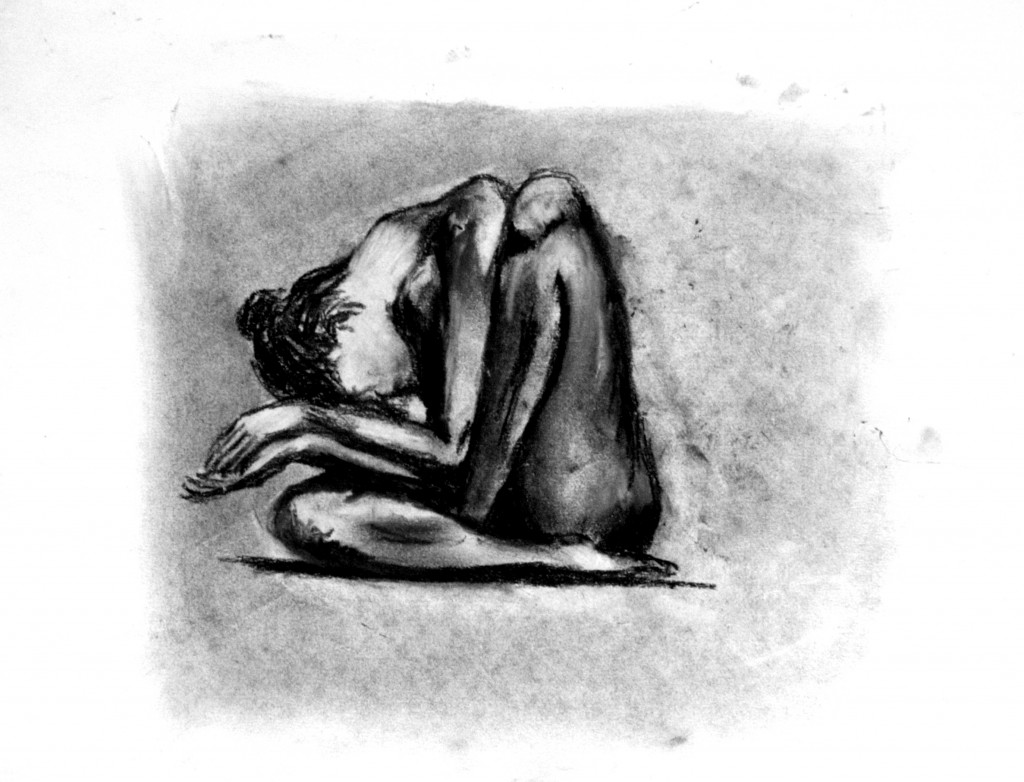

Life modeling forces me to see my nakedness in a new way. Countless times I have stood or sat, conscious of my own heaviness, my physical mass, and how it seems to root itself to the platform, only to be surprised by the ephemerality of the images scattered across the floor of the studio afterwards. In these images I am small, airy, smudged. I am barely there. Other experiences are more intimate. During one session with a group of high school students, I arranged myself on my side with my knees drawn up to my chest, one slightly higher than the other. I slowly became aware that a girl had positioned herself directly facing my pudendum, now revealed at an angle that I had certainly never seen with my own eyes. Ferociously aware of the underside of my vagina, I was initially embarrassed, then curious to see what kind of drawing she would produce, and then not a little impressed by her audacity. And though the point of view was lewd—at best Egon Schiele, at worst hard-core porn—the image she drew, whilst remaining vulva-like, was powerful, abstract, unusual. In drawing what was, to me, the most private, vulnerable part of myself, she carried it outside of that realm and gave it an aesthetic. The power of transformation belongs to her.

As the model, you willingly submit to the most intense gaze in human society: the artist’s. It is easy—too easy, really—to imagine the paintbrush, charcoal, inkbrush, or pencil tracing your outlines as a hand upon those curves. I like to watch my artists (at least, those I can see) and watch what they do when they come to my erogenous zones. Some are stoics, others flinchers. I find it amazingly erotic to be the subject of so much attention—worship, even. As the drawers mill around searching for new materials, sometimes they set things down by my feet, and I am met with a string of people rummaging for charcoal, leaving their dirty deposits on the bench as offerings.

But for the most part, they see right through me—it is apparent in their concentration. For them, I fluctuate between existing as a naked person and a series of shapes, contours, and shadows. It depends on what they are looking for that day and on how I am lit or presented. When the break comes, the atmosphere snaps, and I am no longer the center of attention. Tired of looking at me, their object, the artists step back to look at their easels, and examine their own hands.