Last year, I embarked on a mission at the behest of the great American inventor Greg Steiner, whose legend preceded him, as legends often do in the era of the World Wide Web. I discovered him while searching for what remained of the workbench tinkerer. Lacking fluency in the arcane languages of the high-tech tools that had come to govern my life, and armed with a degree in history, of all things, I feared being cut off by the 21st century’s blade of progress. I wanted some assurance that the tinkerer lived on.

Steiner is, after all, the creator of the famous Squeeze Breeze, a hand-held spray bottle with an attached fan that allows users to cool off by misting themselves during, say, a Little League practice. The Squeeze Breeze is the epitome of what he calls “junk inventions,” items that can be made in five hours or less. Having sold 80 million units, Steiner is king of the junk inventors. And here he was, offering his Midas touch to wannabes like myself. On Steiner’s website, an Einstein-esque caricature named Professor Thinksalot declares his noble intentions: “Sincerely Helping the First Time Inventor.”

I had read that the wellspring of Yankee ingenuity had slowed to a trickle. After Eli Whitney ’92 (that’s 1792) invented the cotton gin, Yalies all but ditched the business of simpler machines. The inventors of yore—Ben Franklin and the like, whose Eureka moments became the stuff of American folktales—were consolidated in corporate R&D departments, which discouraged the more radical, harebrained, and heroic breakthroughs of decentralized innovation. Individuals in the U.S. are granted fewer patents today than they were in the seventies, both on a per capita basis and as a percentage of overall patents issued.

I wondered what had become of the tinkerers who comprised that shrinking sliver, and how, in this day and age, they could ride their ideas to the top. So I decided to try it myself.

Like any good junk inventor, I had an eye on life’s smallest, peskiest, and least-addressed problems. Loofahs grow moldy, dryers turn socks inside out, car seats overheat when you park in the sun. Solving these issues is hardly a priority for the human race, but if everyone aimed for the Nobel Prize, the shoelace would never have been invented.

Professor Thinksalot offered a list of “the most important inventions” to help me on my way: Telephone, Light Bulb, Microwave, Airplane, Printing Press, Computer, Skateboard, Pacemaker, Can Opener. I clicked on “Inventors Club,” and entered my name and email address while membership was still free. When the site failed to process my request, I called the number for the company’s office in Downers Grove, Illinois, and was greeted by the shrill buzz of corporate extinction.

But in the days that followed, the idea came to me. ‘Eureka!’ as they say.

***

I encountered many naysayers on my journey from idea to product, but rejection only hardened my resolve to forge ahead. I entered in the Yale Entrepreneurial Society’s “Elevator Pitch Competition” with a shot at winning $300, but I never even got to present my idea to the judges. I also entered in the “What’s your thousand dollar idea?” competition sponsored by a student hacking group called Y-Hack, and I finished in ninth place, behind seven proposals for software applications and one for a t-shirt brand.

Forsaken by Steiner, Thinksalot, and my classmates, I sought a local support group in the Inventors’ Association of Connecticut, hoping to pick up some pearls of wisdom from industry veterans and meet other innovatively inclined Average Joes. At the IACT monthly meeting, a few dozen people a few dozen years older than me gathered to discuss their hopes, their fears, and—with shifty eyes and cautious words—their ideas. When their leader, Dr. Douglas Lyon, a short, sinewy man with a stringy ponytail and a Ph.D. in Computer and Systems Engineering, asked me to introduce myself to the group, I told them I was an aspiring first-time inventor in my senior year at Yale, majoring in history.

“Oh, so you invented history?” quipped an elderly man in the group. The room erupted in laughter.

“I’m reminded of an old joke,” Dr. Lyon chimed in. “You can tell a man’s profession by the way he responds to a new invention. The engineer asks, ‘How does it work?’ The accountant asks, ‘How much does it cost?’ The history major asks, ‘You want fries with that?’”

Again, the crowd went wild.

Tail between my legs, I returned to the Internet to seek other help. A cursory Google search returned a handful of companies advertising their ability to turn inventors’ ideas into high-grossing products—dream factories, I thought. I completed the forms provided and submitted my idea. Before long, my phone was ringing off the hook with calls from representatives all over the country, eager to lend me their wisdom. Needless to say, I was flattered.

***

When I walked into his office in Braintree, Massachusetts, Carl Cook, a New Product Recruiter for Invents Company, LLC, asked me to sign a form acknowledging that the odds were not in my favor.

“Ninety-one thousand people have sat in your shoes,” Cook said, and that was just last year. Of those hopeful inventors, a mere 381 made it to the next stage, in which the company’s researchers, engineers, and marketers get involved. From that point, just eleven inventions made a profit for their inventors.

We met in a three-room suite across the hall from American Laser Skincare (whose door promises “Beauty Through Technology”) in Braintree Executive Park. The reception area bookshelf was decorated with “As Seen On TV” inventions: the Booty Slide, the Lint Lizard, Silly Slippeez, the Sift & Toss. Cook’s sole colleague at Invents Company’s so-called Boston office was Bruce, a portly, avuncular man roughly one decade Cook’s elder. Both employees wore black-gray paisley-patterned ties and had ruddy complexions.

Cook explained the company’s services: a patent search and feasibility report ($800 to $1,100) and then, should the projections look promising, representation (another $8,000 to $11,000). It wasn’t cheap, but I was beginning to believe in my idea. Besides, only a coward folds a royal flush. Moreover, I didn’t have to put down any money just yet. I charged ahead with my pitch and slid the preliminary sketches across the table.

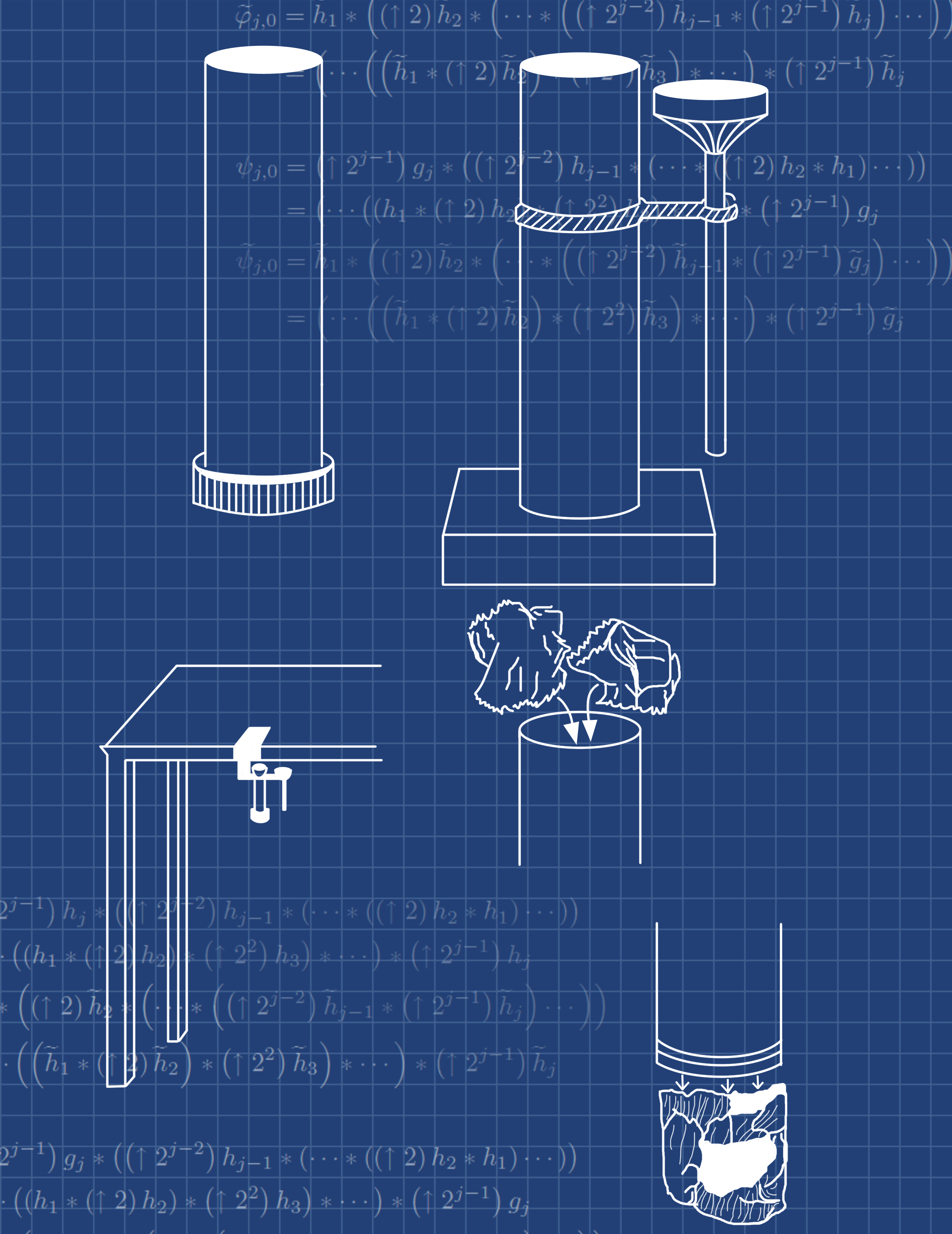

I call it the Wrapper-Compactor: a little tube for disposing wrappers and other small pieces of trash, complete with a little plunger to cram them into the bottom. Never again would Cook have to worry about the detritus generated by the dish of Jolly Ranchers on his desk. I could tell he was impressed. He submitted my idea to Tom D’Francesco, at the New York office, for review.

“If anybody,” D’Francesco told me over the phone, “—myself, Carl, anybody—tells you, ‘Yeah you have a great idea,’ they’re blowing smoke up your butt.” I tried not to let his gruff manner discourage me. “If we went on every inventor’s gut feelings, I don’t even wanna tell you where we’d be.”

I asked for more information on Invents Company’s top products, but he dodged the question. His advice was simple: “Don’t compare yourself. Don’t get caught up on the products that made it. Focus on all the products that didn’t make it. Find out why they didn’t make it.” Defiantly eager to behold success, I called up one of the inventors touted on the Invents Company website.

***

Anthony Capozzo lives on a quiet street in Milford, Connecticut, with his wife and two children, in a house with central heating, bathrooms, and a backyard deck fashioned with his own two hands. He makes a living repairing washing machines, dryers, microwaves, and refrigerators, and has mounds of spare parts stockpiled in his own personal man cave. He also sawed a hole in the ceiling so that he has space to practice his golf swing.

The ultimate do-it-yourselfer, Capozzo invented the Sure Tarp, a tarp with weighted edges, so that when a storm blows in, you can cover your gear quickly (no need for bungee cords) and head indoors. He took his idea on the train into Manhattan, entered a 7th Avenue skyscraper and rode the elevator up to the 11th floor, where a representative named Phil laid out the total cost of his venture with Invents Company: $12,000. This was out of Capozzo’s price range, but when he pitched the investment to his siblings, they got on board. The Capozzos love to gamble, he says, and the Sure Tarp was an once-in-a-lifetime opportunity.

After completing the initial research, Invents Company developed a thirty-second television commercial to gauge consumer interest in the Sure Tarp. Despite D’Francesco’s claim that the company runs ads in carefully calculated locations to get an accurate understanding of the product’s potential, the ad ran a total of four times exclusively in San Diego, where the average annual precipitation is less than twelve inches. By comparison, Capozzo’s hometown of Milford gets 50 inches per year. Though consumer response was positive, Capozzo was told, none of the 30,000 manufacturers in the Invents Company network were interested in producing the invention.

When I visited Capozzo at home, I saw that the firewood in his backyard is covered by an old-fashioned tarp. It had been there ever since his prototype broke. He has vented about the debacle to his next-door neighbor, Bob. We meandered over to Bob’s stoop, and Bob launched into a rant about those insufferably out-of-touch New Yorkers who let the Sure Tarp die. It’s a conversation the two friends have rehashed time and time again.

“We all hope Tony gets rich!” Bob said.

“No, I don’t wanna get rich, Bob,” Capozzo replied. “I just wanna pay my mortgage off.”

***

When Cook informed me that Invents Company had decided to pass on the Wrapper-Compactor, I chalked it up to bureaucratic myopia and turned my attention to the other suitors who had been flooding my voicemail with eager entreaties.

There was Bob White, of Patently Brilliant, who told me, “Yours is a long term product—it’ll be around for a long, long time,” and informed me of the $800 pay-to-play fee.

There was Didier from Miami who, before even mentioning the price tag for his company’s services, asked, “Are you doing this alone or do you have support from your family?”

But there was one man who seemed different than the rest. His name is Stephen P. Gnass, and inventors of all stripes sing his praises on the testimonials page of his website.

“I have come to depend on him to protect me from my own excitement to keep me from making a poor decision,” confess the inventors of the Swivel Car Seat.

“Stephen has a seemingly bottomless wellspring of knowledge,” writes the creator of Bliss Trips: Guided Journey CDs.

“You zeroed in on what we needed to do and showed us exactly how to move towards bringing our dreams to fruition,” attest the inventors of the Metra Stress Reducer.

Gnass’ website describes him as a TV-famous “inventors’ advocate.” Though he holds no patents himself, he has made a career of advising inventors. He offers prospective clients a thirty-minute “free complimentary brainstorm,” just the sort of no-strings wisdom I’d been looking for. Before our call, I consulted his “Successtimonials” page, where I read of Gaile Spalione, inventor of Mop Flops. I decided to track her down.

***

When I reached Spalione at her home in Reseda, California, she was babysitting her grandchildren. She conceived of dual-purpose footwear around seventeen years ago, as she bustled about the house caring for her children and dreamed of a way to collapse two domestic duties into one. She took her idea to a variety of companies, and ended up losing $25,000 to crooked people who promised much and delivered nothing. She attempted to file suit against one such racketeer, Davison & Associates, but was ultimately unable to recoup any losses.

In 2000, Spalione filed for and received a patent, paid to manufacture a first round of booties, and produced a commercial for a local television station. The cost was exorbitant, but her mother generously mortgaged her house to help fund the venture.

Still looking for ways to promote her product, she found a convention geared for inventors looking to market their wares. She paid the entrance fee and set up a booth to promote her product. At the convention she met the organizer, Stephen P. Gnass. He offered her a free consultation, and the two quickly developed a rapport.

“Dear Stephen,” Spalione’s Successtimonial reads, “I must take this opportunity to express my sincerest gratitude for having your sound advice and wisdom guiding me through this tangled invention process. You are my rock!”

The piles of unsold Mop Flops in Ms. Spalione’s garage—roughly 2,000 pairs—offer a markedly less reassuring testament to the difficulty of making it as an inventor. She had contacted a Chinese manufacturer in hopes of lowering production costs, but when the shipment arrived, she discovered the measurements had been lost in translation, leaving her with a lifetime supply of Mop Flops too miniature to wear.

Though Spalione doesn’t regret the venture and remains a devotee of Gnass, she admits disappointment at the outcome.

“I was hoping my idea would take off and I would become a millionaire overnight,” she recalled wistfully. “I’m still waiting.”

***

For Spalione and countless other would-be inventors facing similar marketing and supply-chain complications, the prospect of a one-stop-shop that shepherds you from idea to product is a tempting one. But as I learned from Gnass during our complimentary conversation, it’s never that easy.

“You would think that there would be a company that does it all for you,” Gnass told me. “Just hire them and they’ll do the drawing, make the prototype, give you the book, do the research, and take the invention to trade shows.” That was exactly the impression I’d been under.

My associates at Invents and elsewhere had led me to believe they could magically bring my idea into reality. But having gone toe-to-toe with these companies for decades, Gnass wanted to set the record straight: “They don’t make their money from the invention, they make their money from the inventor. They’re not stealing inventions or anything like that because that’s not where they make their money.”

In other words, they operate by selling inventors’ ideas back to the inventors themselves. The multi-phase, official-sounding process does little to advance the product to market. Instead, it exists to enamor inventors of their own ideas. These companies charge a small fortune and deliver their clients an overestimate of market demand and an exaggerated feasibility report.

The world of analog innovation these days requires more than ingenuity and elbow grease; at some point, you have to call in the professionals. The creation of an inventing industry within corporate R&D departments leaves outside inventors to navigate an obstacle course that almost always costs them thousands of dollars before they give up and leave their idea by the wayside. Whereas software developers or app inventors—the tinkerers of my generation—can go from concept to market without lifting a finger from Home Row, junk inventors depend on entities much larger than themselves. Even a genius can no longer act alone—and that leaves him vulnerable. That’s why companies like Invents Company exist, and why they will continue to exist as long as average Americans like myself dream, even of junk, beyond our means.

John Stillman is a 2014 graduate of Yale College.