Hudson Street, just off of Whalley Avenue, looks like any other street after a hard winter. The asphalt is pocked with fresh potholes, the sidewalks cracked from months of ice. Debris litters the edges of the road—stray tires, plastic bottles, scraps of clothing, a discarded pair of shoes. The shoes look like black-and-white low-top Converse, but their rubber soles are thinner and flimsier, and the ripped canvas bears no insignia. They are state-issued prison sneakers, given to inmates by the Department of Correction

On one side of the street is a row of houses with small front yards; on the other is a row of cellblocks behind barbed wire. This is the New Haven Community Correctional Center, commonly known as Whalley Jail.

Roughly eighty male prisoners are released each month at the jail’s back gate on Hudson Street. On average, twenty-five of these men are released directly from the county jail. The rest are dropped there from prisons all over Connecticut. They walk out in the early morning hours, quietly and inconspicuously.

At around 6:30 a.m., a white minibus with gold and blue trim pulls into the gate’s entryway. A correctional officer sits in the driver’s seat holding a clipboard. The passenger windows are tinted and reinforced with metal mesh. The gate slides open, and the bus drives through. After a moment, the gate closes.

The officer walks into the building and returns a few minutes later. He opens the door of the bus, and three men file out. They wear DOC-issued clothing—long-sleeved white shirts and loose white or tan pants. Each man’s wrists are bound by metal cuffs that connect to a chain around his waist. They rattle as they walk through the sally port, the controlled release area at the back of Whalley Jail.

***

At 7:00 a.m., the three men reemerge. The cuffs are gone. In place of prison tans, one man now wears a pair of blue jeans. Another wears a checkered flannel shirt. Each man holds a brown paper bag full of his possessions.

They stand behind the gate, waiting for it to open. The man in the middle bounces up and down.

“I fuckin’ hate this place,” he says, as much to himself as to the two men beside him, who nod in agreement.

The gate begins to open. As soon as it slides wide enough to fit through, the three men rush out onto the sidewalk, smiling. Two of them take a left out of the gate and begin walking toward Whalley Avenue.

“You got any smokes?” one man asks me as he passes by.

“Nah man, sorry.”

The third man, still in full prison clothes, turns right out of the gate. He is practically running, but he stops when he sees the pair of shoes on the sidewalk.

“Somebody left they skippies,” he says, laughing. He pauses, then continues down the street. He rounds the corner. Only moments have passed since the gate opened, and already all three men have disappeared from view. But where are they going?

An inmate in the Connecticut DOC can arrange to be picked up at the end of his sentence from the facility where he has served his time. He also has the option of requesting DOC transport to one of four drop-off sites: Middletown Courthouse, Hartford Courthouse, Bridgeport Correctional Center, or New Haven Correctional Center. If there is no one to pick him up from the drop-off site he chooses, the DOC provides a 90-minute bus pass upon release. Men who choose to be dropped off at Whalley Jail typically return to New Haven or to a nearby town. The same is true for women, who are let out near the police department headquarters on Union Avenue.

I went to Whalley Jail each morning for two weeks to meet men as they were released. Even those who had been incarcerated for a short time—less than a year—spoke of the anxiety of reintegration and the uncertainty of what lay ahead. After a long period of living under prison conditions, the first steps back into society can be overwhelming. The world they return to is neither fully prepared nor totally willing to support men coming out of prison. Employment is hard to come by, especially while many ex-offenders grapple with housing instability or chronic health problems. Returning to high-risk areas can trigger relapse, into substance abuse or crime.

A 2008 study by the Connecticut Department of Corrections found that forty-seven percent of ex-offenders return to prison within two years of release, twenty-one percent within the first six months. Yet many New Haven residents regard ex-offenders as a threat, rather than a population in need. Several years ago, the local community protested the release of the men directly onto the busy thoroughfare of Whalley Avenue. For that reason, they now walk onto sleepy Hudson Street, out of sight and out of mind.

***

I follow the two men who turned left out of the gate. I find them sitting in a booth at the McDonald’s across Whalley Avenue.

“How you guys doing?” I ask

“Doin’ good man.”

“Better than yesterday.”

The man in blue jeans who asked me for cigarettes outside the jail gate tells me his name is Steven. The correctional officer at the sally port gave him the jeans, left behind by another inmate. He wears them in place of the tans he arrived in. His off-white, long-sleeved T-shirt and white sneakers are his from before his stint inside.

His salt-and-pepper hair is buzz cut, and his clean-shaven cheeks are nicked with small scars. He has a wheezy laugh and a wry smile that curls up on one side of his mouth. He is 49 years old.

Paul, the other man, is muscular, with a handsome, chiseled face and short brown hair. He takes off his checkered flannel shirt (also given to him at the sally port) to reveal a blue Catholic cross tattooed along the side of his right bicep. He is 34. He wears black-and-white canvas “skippies,” like the ones left on the sidewalk, and he tells me his feet are still freezing from the cold walk.

Paul picks up the flannel shirt and walks over to a table where an old man in a raggedy winter jacket sits watching television. He drapes the shirt over the back of the man’s chair and comes back to our booth.

“He needs it more than I do,” Paul says, gesturing with his thumb to the man, who has put the shirt on his lap.

“Damn straight,” Steven replies.

Paul pulls on a gray sweatshirt with “NHCC” written under the collar in black block letters. He hunches over, his elbows on the table. He drums his fingers and taps his feet, before opening up his crinkled brown bag. Paul spreads some of the letters, notebooks, paperwork, and pamphlets he collected while in prison out on the table. He fiddles with a folder labeled “Reentry and Transitions.” Steven sets his bag on the table but leaves it rolled up.

Steven has just done eight months in the Corrigan-Radgowski Correctional Center, a combined level three and four high-security prison in Uncasville, where he served time for a domestic violence charge after he threatened his wife—in his case, a Class A misdemeanor. He was originally sentenced to nine months, but he was released one month early for good behavior. He now has two years of probation.

Paul was charged with domestic violence for threatening his ex-girlfriend. He spent three months of his six-month sentence in Radgowski before transferring to a lower-security section of Niantic Annex, where he completed his time. He, too, will be on probation for two years.

Neither of the men is from New Haven, but they chose to be dropped off at Whalley Jail because it is the facility closest to their homes. Steven is from Meriden, Paul from Northford. Steven’s sister should arrive at 8:30 a.m., so he has an hour-and-a-half to kill. Paul uses my phone to call his girlfriend, due to arrive any minute.

“It always feels weird to be coming outta there into society,” Steven says. “We don’t even got normal clothes to wear, so people can spot us easy and tell where we come from. Feels like people are looking at us like we’re crazy. But really they don’t know.”

He smiles and looks at me as though I and everyone else in the McDonald’s are missing an inside joke. Steven has spent fifteen years of his life behind bars for various charges. He was out for four years before his most recent bid. When I ask him how it feels to be out this time, he shrugs.

“When you’re outta society for so long it just seems like a different world. I mean, I’m just dying to see a twenty-dollar bill. Just the simplest things in life are big right now,” he says.

The men speak with bitterness about the prison conditions they just left, focusing on the difficulty of living without privacy.

“Niantic Annex is a fuckin’ nightmare. It’s level two security, so you think it’s supposed to be better, but it’s fuckin’ terrible,” Paul says.

He tells me that sixty men slept in the bunks on either side of him.

“They’d roll over in their sleep and knock me in the head,” he continues. “There’s nowhere to go. You’re trapped in this little room with no air. You either sit on your bunk or you sit next to your bunk. For months. There’s no movement. You’re depressed ’cause you can’t even walk.”

The men focus on the small details of daily life: the uncomfortable sleep, the cold food, the placement of the toilets.

“I was in a room with fourteen people,” Steven says of the Corrigan-Radgowski Correctional Center. “Living shoulder to shoulder. All of us using one bathroom. They don’t give you no supplies neither. When you get in they give you a little piece of soap”—he measures a two-inch bar of soap with his fingers—“and the state deodorant, which is like water. When you go to the counselor to ask for something, they say they don’t have nothing. Tell you to bum it off of one of the other inmates.”

Steven tells me there is no hot water allowed in the cells, as hot water can be used as a weapon. To heat food from the commissary, inmates improvise by making a “stinger.” You take an extension cord and cut it open with a pair of nail-clippers, he explains. You pull out the exposed wires, the neutral and the hot, and put a plastic spoon between them. The wires can’t touch. You wrap a scrap of metal around the spoon and wires, stick the end in a tub of water, and plug in the cord. It’s essentially a dead short circuit. Then you wrap your food in a garbage bag and put it in to warm.

Steven and Paul agree, though, that in many ways reentry is much more intimidating than prison.

“When we come out, it’s not over,” Steven says. “This is the bad part. Jail’s easy. Inside you got no responsibility. You get up, you eat, you shit, you take a shower, you go back to sleep. They tell you when to do everything. This is the real life out here. You gotta figure out which way to turn.”

Paul nods in agreement. The six-month sentence that ended today has been his only time served since a five-year stint after he left the Navy in 2002. He shifts in his seat and fidgets with his belongings. Whenever a car pulls into the parking lot, he hoists himself up to peer through the window, asking, “Is that my girl?”

***

Joseph Roach, who works as a counselor at Whalley Jail, says that the DOC cannot control the circumstances before or after an inmate’s sentence. A soft-spoken, middle-aged man with round-framed glasses, Roach tells me they can only help an inmate while he is incarcerated.

“If you don’t take the time to take advantage of [what’s offered] until the last minute desperation, you’re gonna struggle. And then you’ll say it was the system that messed you up,” he says.

But there is sometimes a disconnect between the perceptions of prison staff and inmates who believe the system is set up solely to punish them. Both Steve and Paul enrolled in reentry classes to improve their chances of getting out on parole, but both were denied. Steven is convinced that the DOC offers the classes only to receive funding from the state and federal governments. He says his instructor did not care whether the inmates participated, only that they showed up. Paul relates a similar experience.

“The classes they offer are ridiculous,” Paul says, shaking his head. “It’s a scam. The whole thing in there is money.”

Paul says he wrote to the counselor supervisor and the reentry counselor at Radgowski asking for help finding reentry programs and employment options after release. In the McDonald’s, he flattens two formal request sheets, one for each counselor, out on the table and points to their responses under his notes. One told him to consult with his probation officer after getting out, and the other said that what Paul asked for was not under the counselor’s authority.

It is difficult to ascribe blame in a situation like Paul’s without full knowledge of the facts. Just as there are prisoners who do not make the effort to engage with resources, there are counselors who do not care and simply go through the motions of their job. The real issue emerges when jaded prisoners stop seeking out resources and stumble along without support.

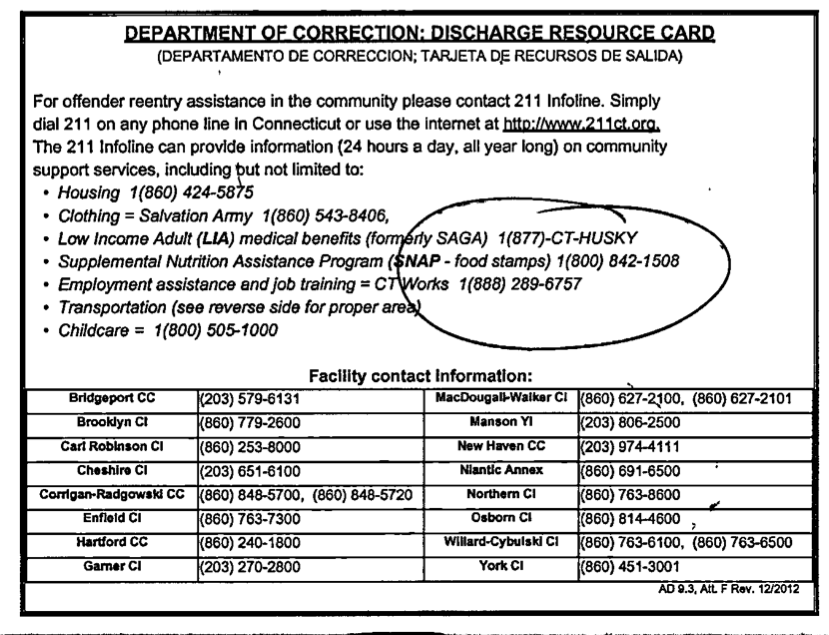

Paul reaches into his paper bag and pulls out a laminated rectangular card, which reads DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS: DISCHARGE RESOURCE CARD.

“They give you this and basically tell you to kick rocks,” he says dismissively. “A list of shelters. I’m not going to a shelter.”

I look at the card. It isn’t a list of shelters. It’s a list of phone numbers that access a general reentry assistance line, housing authority, The Salvation Army, low-income adult medical benefits, food stamps, the employment-assistance organization, and childcare services.

New Haven’s city government works to keep the formerly incarcerated informed about all available resources. Project Fresh Start, a reentry service the mayor’s office launched in January, assists anyone with a criminal record. The program serves as a bridge between ex-offenders and specialized resources: sober houses, job training, mental health care providers, adult education centers, health clinics, the housing authority, and more. Chance Jackson, one of the program’s coordinators, tells me Project Fresh Start should be a “mecca” for ex-offenders, with ties to every reentry resource in New Haven.

Around 260 people walk into Project Fresh Start’s office at City Hall each month, but lack of awareness persists in the larger ex-offender community. Every reentry service I spoke to, from Project Fresh Start to CT Works to Project MORE (an ex-offender reintegration organization) to Transitions Clinic—a free health clinic for ex-offenders with chronic ailments—told me there needs to be more outreach before release, so that men in prison have a sense of what options await them when they get out and can prepare accordingly.

While some programs send representatives to speak with inmates and initiate personalized plans with clients before release, most rely on word of mouth to draw ex-offenders to their offices. Jackson explained that he often meets people who have been out of prison for months and have struggled on the streets before finally connecting with Project Fresh Start.

Jerry Smart, a community health worker at Transitions Clinic, which aims to serve the roughly eighty percent of ex-offenders who come out of prison dealing with chronic illness, put it plainly:

“I’d like to see us connect with prisoners at least three to six months prior to their coming home, to build a rapport with them and come up with an action plan,” Smart says. “If you’ve got this dream of getting a job and house, and you don’t have no skills and no résumé and basically no contacts, how you gonna make that work without a support system?”

Ryan, another ex-offender, had just completed a nine-month sentence when we met on the morning of his release. He was in an intensive drug rehabilitation program at Carl Robinson Correctional Institution in Enfield, where he says he spent his days filling notebooks with plans for the future. He had been incarcerated twice for violating his probation through drug use, but was determined to stay clean through Alcoholics Anonymous and Narcotics Anonymous meetings. His past incarcerations caused two “false starts” with community college, but he planned to enroll in Middlesex Community College in Middletown as soon as possible.

“People who get out of jail and say, ‘I don’t know what to do or where to go,’ they just didn’t try,” Ryan tells me. “Some people do fall through the cracks, and sometimes it’s on the DOC, but if you put in a little bit of work, they’re gonna help you out.”

***

Paul’s and Steven’s greatest advantage, even if they deny the help of nonprofits, is that they have families waiting for them. The support of relatives can ease the transition back to the rhythms of daily life.

Steven’s sister helped him develop a clear plan for the coming days. She is going to pick him up, and she has an apartment ready for him back in Meriden, as long as he can get a job and pay rent. He’s planning to go back to tree removal, his old line of work.

“Without her, I’d have to go to a shelter,” he says. “I wouldn’t even be here right now. I’d be walking down Whalley Avenue blind, not knowing where I’m gonna pick up a dollar bill.”

But negotiating family relationships can also be fraught with difficulty. Steven tells me his biggest concern is reconnecting with his wife of fifteen years, with whom he has two sons. She has a protective order against him and did not write him during his sentence.

Easter weekend is coming up, and Steven believes that his wife will contact him when he returns to Meriden. “I want to be with my wife and kids for the holiday, eating ham,” he says. “But I’m on thin ice.”

Because of the protective order, any reports of abusive or threatening behavior on his part will likely be a violation of Steven’s probation, which could send him back to prison for up to three-and-a-half years. This is a common problem for ex-offenders with histories of abuse. William “June Boy” Outlaw, a community advocate at Easter Seals Goodwill Reentry, a New Haven program that serves high- to moderate-risk ex-offenders in New Haven, explains to me that a record of domestic violence raises an immediate red flag.

“If I see domestic violence on a client’s record I wanna get into that,” Outlaw tells me. “I wanna know do he intend to reconcile the dispute. Because those never reconcile. The woman he was with knows the button to put him back in jail. She can call the police and say your name”—he snaps his fingers—“and that’s it. If you don’t go back, you take yourself out of that high-risk situation, which is usually better for everybody.”

Paul tells Steven he should cut ties altogether.

That is what Paul has decided to do with his ex-girlfriend, with whom he has three-year-old twins. His only tie to her now is the child support he owes.

“You’re not free when you get outta jail,” Paul says. “I owe four grand and counting in child support. I gotta go to probation meetings and domestic violence classes. I gotta get a job.”

Paul clenches his hands together and grits his teeth. He has none of Steven’s coolness, perhaps because he has been in and out of prison less often than the older man.

“I got anxiety bad,” he says. “I been planning this shit for two months and I don’t know what the fuck to do with myself. My heart’s racing, man.”

Steven laughs. Paul doesn’t.

Paul’s biggest concern is that he won’t be able to land a job. He is required to attend a domestic violence class once a week and meet with his probation officer three times a month, which he believes could make him miss work seven times a month. He does not know how he will afford child support.

Paul stands up from the McDonald’s booth and looks out the window. The woman who is picking him up has pulled into the parking lot. He sits back down and repacks his bag.

“I’m shittin’ my pants, man,” Paul says to Steven and me. “I’m thinking of leaving the state. I wanna go to New Mexico. I been there once. It’s beautiful.”

Going to New Mexico without permission would be a violation of Paul’s probation, which could lead to a five-year prison sentence.

Steven chuckles as Paul walks to the door to meet a young woman, whom he greets with a “My girl!” They embrace, and Paul follows the woman to her car.

A man walks over to where Steven and I are sitting and offers him a cigarette. Steven takes it. He borrows the man’s lighter to walk outside and smoke.

Steven hasn’t had a cigarette in eight months. He takes a slow drag and blows smoke toward Whalley Jail across the avenue.

He remains calm as he speaks of reentry, though he cannot know exactly where he’s headed. “It’s scary when you come out,” he says. “You feel like you lost everything. There’s obstacles, but I think positive. You can’t let things overwhelm you. That kid, he was getting overwhelmed. You just gotta wait it out. Like my mother always said, ‘You don’t get things overnight, and when you do you don’t appreciate them.’ When I get something I wanna appreciate it.”

I thank Steven for speaking with me. He nods. I leave him standing outside the McDonald’s. The morning is still cold and raw. He cups the cigarette in the palm of his hand, out of the wind.