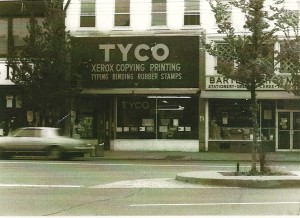

The printer on the second floor of Tyco beats like the heartbeat of a marathoner gone aerobic. Founded by Michael Iannuzzi in 1971, the copying and printing company is one of the few small business that have seen the transformation of Broadway.

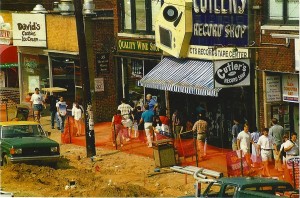

Educated Burgher is another. There, a 1984 map of New Haven’s businesses still hangs on the wall, faded and irrelevant. Fewer than half of the businesses depicted still exist. There was once a movie theater, a wine shop, a record store, a bar, two more Cutler’s outposts, and a florist—but they’ve all gone under, most of their properties bought up by Yale. Today, Campus Customs, Educated Burgher, Blue Jay Cleaners, Toad’s Place, Yorkside, and J. Press are all that remain from the old guard.

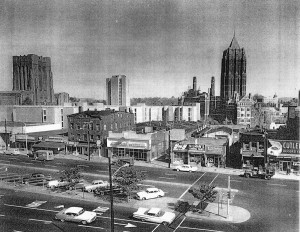

The revolution began with the sidewalks. In the mid-1990s, Yale and New Haven partnered to make infrastructure improvements—changing traffic patterns and storefront signs, renovating buildings, burying utility lines, and planting elm trees—to combat what Iannuzzi classified as the sentiment that, as an urban area, “we were decaying, but not from the standpoint of the business.” The New York Times put it more bluntly in 1994, stating that the area was “plagued by traffic congestion and rampant shabbiness.” Yale’s goal was to make it more welcoming—to students, businesses, and those in the community.

According to Bruce Alexander ’65, the Vice President for Yale’s office of New Haven and State Affairs (NHSA), the transformation he initially imagined ten years ago is almost complete—only the installation of a handful of fine dining spots remain. The change has been made possible by Yale’s careful management of inter-store competition. Yale, which owns most of the properties, leases to stable corporate businesses such as J.Crew, Origins, and Au Bon Pain.

The University began buying up properties from local New Haven families who wanted to sell, a process accelerated when university president Richard Levin hired Alexander in 1998. Alexander aggressively recruited new merchants such as Laila Rowe, Urban Outfitters, and Thom Browne, and brought in Ivy Noodle to serve late-night dining needs. In a 2001 press release, then-University Properties financial analyst Andrea Pizziconi ’01 said that to identify an appropriate 24-hour convenience store “we literally walked the streets of New York for days,” before deciding on Gourmet Heaven. “I don’t think the Yale community realizes it,” she said. “But Yale is doing some of the most innovative and aggressive development projects among universities throughout the country.”

One of the biggest changes was to introduce national corporations to Broadway—the first of which was Barnes and Noble. Independent businesses owners often fear that corporations will be aloof and dissociated. In the merchant’s association of Broadway, however, Iannuzzi said the bookstore is “progressive and aggressive in being a part of the community,” a refreshing reprisal for the smaller businesses. Despite this diplomatic courtesy, phrases like “elbow their way” found their way out of the mouths of both Iannuzzi and Barry Cobden, manager of Campus Customs, when they spoke of larger companies. Iannuzzi observed that the arrival of stores like J. Crew on a city block signaled a change in shopping culture — a decade ago, he claimed, they would have stayed in the malls. “A lot of times you lose if you get a corporate coming in,” he concluded. That said, New Haven does not have a significant department store to draw in traffic, so Barnes and Noble now acts as an economic anchor. “The nice part about the area,” Iannuzzi continued. “Is that Yale has sort of wrapped around the idea that the environment is for the students and the city.”

The newest addition to the Broadway Shopping District, Gant, opened this November. Founded in New Haven in 1949, the now Swiss-owned purveyor of American sportswear has 590 stores worldwide, and likes the idea of “coming home,” said Ari Hoffman, CEO of Gant U.S.A. in an interview with the New Haven Independent in October. “Some people may say, ‘Paris, Milan, Italy.’ We say, ‘New Haven.’”

Gant’s webpage credits founder Bernard Gant with introducing the classic “button-down shirt” and outfitting “the good life and leisurely lifestyles on the American East Coast.” Mr. Gant arrived on that coast in 1914, a Ukrainian emigrant who found employment in New York City’s garment district. Yet the company uses definitively WASP iconography to woo its customers. The New Haven Gant store displays Take Ivy, a photograph collection of Ivy League fashion in the sixties, at the register. The Gant catalogue narrates in saccharine stereotypes the lives Gant men and women living in Washington D.C., offering poetical summaries of lacrosse games and the social lives of politicians. A reflection on “The Art of Networking” fills the back pages. When Gant’s imminent arrival was announced in October, Abigail Rider, Director of University Properties, said, “the addition of Gant to the retailers on Broadway reaffirms our connection with our New England traditions.” Gant’s presence suggests that these are perhaps traditions of aspiration—though only time will tell if pricey flannel and football jackets will keep the store around.

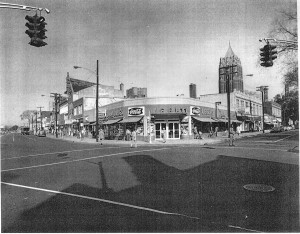

After all, University backing doesn’t guarantee a business’ success. Establishing a commercial business remains an exercise in hope and crossed fingers. Even when all the operative variables are aligned, unexpected failures occur. Johnson, Iannuzzi, and Cobden spoke of Kerin, an pricy eco-fashion store that lasted less than a year at the southwest corner of Broadway and York in the space that Gant now occupies. “I think people just thought, well it’s Yale so we can go really high-end,” Johnson mused. Kerin is not the only business that has failed in recent years. Whimsel’s, a creperie owned by two Yale graduates, closed less than two years after opening. York Square Cinema stopped playing films in 2005 after years of struggling with motion picture companies to obtain rights to blockbuster films. Cosi closed in 2008, citing a drop in customers.

The current make-up of the block reflects a comprehensive and systematic plan for the development and operation of the Broadway district by the two groups that possess nearly all the real estate. Besides Yale, the largest landowner in the Broadway district is the Vitigliano family. These New Haven real estate magnates own the buildings where Campus Customs hawks Yale gear, Urban Outfitters sells trendy clothing, and the Educated Burgher serves up greasy diner food.

In December 2003 the holdings of the Vitigliano family were placed in the care of a real estate investment group called the Yale Mall Partnership, which represents the shared property of the Vitagliano siblings, according to the online records of the New Haven town clerk. The Vitaglianos have worked alongside Yale’s urban renewal initiatives, entering into multiple agreements with the University regarding leasing practices on the block since 2007.

From their University Properties office, Yale arranges extensive Broadway promotion, including College Night, which draws students from local colleges and universities for a night of discounts, live music, and prizes. According to Cobden, Iannuzzi, and Anne Johnson, the manager of Laila Rowe, the night provides increased profits for the stores that take part. All three credited Yale for planning and promoting the event–the university, in its role as landlord, even arranged for the sidewalks to be cleaned before and after. That dual act of promotion and maintenance is a part of the regular routine on Broadway. Drew Ruben ’11, owner of Blue State Coffee which has five locations in Boston, Providence, and New Haven, said he is not aware of any other landlord who does so much active marketing for their tenants.

Iannuzzi readily acknowledges that “Yale put together the plan to develop the area. They spent a lot of money and made the place look great.” That said, the extra-special treatment comes at a price. In exchange for its services, Yale requires adherence to certain standards of operation from its occupants. The commandments are few: Stores must stay open until at least 9 o’clock Sunday through Thursday and they must keep generous holiday hours. Gourmet Heaven has to display fresh fruit on the sidewalk. When a tenant breaks the rules, they pay a fine. Yet this strong discipline has strengthened Broadway’s renaissance.

Before Kerin, a fast-food chain claimed the southwest corner on York and Broadway, recalled Johnson. As he tells it, Yale “got them out of there.” The restaurant served lunch and dinner, sold liquor and played music for dancing. They vacated the premises about a year after the property transferred into Yale’s possession, according to Cobden. He says the owners became “disenchanted with the area,” and then cautiously added that he does not know if Yale was involved in the move. It certainly wouldn’t be the only time.

The University has publicly used its ownership to ease out stores that “didn’t add to the district,” as Matt Jacobs ’98, Director of Operations for Yale University Properties in the early ’00s, put it. For example, in 2000, the University refused to renew the lease for the convenience store Krauszer’s, citing its high prices and poor selection. University Properties also cited the failure of Bill Kalogeridis, owner of the Copper Kitchen on Chapel Street, to comply with safety regulations to explain why Yale never offered him the security of five-year lease contract instead of month-to-month payments. In an interview with the Yale Daily News, however, Kalogeridis suggested that the University wanted to force his business out to make room for another boutique.

Cobden acknowledged that the changes Yale has made along the way—the corporate presence, the rules—did not always feel good. But a relativist appreciation for Yale’s involvement prevails. For now, Broadway merchants like Cobden are ready to believe that Yale’s involvement is for the best. “This is not change that really hurts,” he explained. The merchants are not about to bite the hand that feeds them even if it does demand some new discipline. It knows best, after all—at least, that’s the hope.