Sometime during the second or third week of your publishing internship, your boss swivels away from her monitor and asks, “How do you feel about romance?”

You don’t feel anything anymore. You have been photocopying foreign contracts for days, and this has made you numb. Peering meekly from behind a fortress of overstuffed manila files, you repeat, inanely, “Romance?”

Her gaze has already returned to her email. “Yeah. Regency.”

You do feel something about this genre; some might call it “antipathy.” While you grope for the words to express that romance is not, um, your favorite thing, a ream of paper is dumped into your arms, still warm from the office printer. Someone’s baby. Your first client manuscript.

On the commute, put aside your pious Anna Karenina and pull out the Regency romance. Your mouth is grim. You’ll find that within the first two chapters, the duke senses that he could come to love this impudent chit, and though she thinks him a cold-hearted rake, she feels an unwilling attraction. They collide on a windswept moor outside the estate. An ankle gets twisted, a skirt ruined, and they fall muddily into each others’ arms. Gently, he tilts her face up. They kiss, their horses looking on approvingly. Throughout, you make broad notes in the margins in red ink, punctuated by gleeful underlines and spluttering question marks. Fly through the story, rifling through until at last you turn over the final page, look out the window, and see the parking lot of your stop.

Your instructions are simple: write up a brief summary and analysis. Always lead with the verdict—do you recommend this manuscript for acceptance? Explain your reasoning. Make suggestions, providing quotes and citing page numbers. And be nice: this person might be our client, so there’s no point in being nasty. The agent might want to use your critiques in their editorial notes. Sternly, your supervisor warns that a reader’s report is not supposed to be beautiful prose.

Re-read your notes. Reluctantly rein in the snark. The villain’s revenge scheme is confusing, you opine, and he could probably kidnap the lady without stealing the identity of a dead naval officer and blackmailing a saucy tavern wench. The banter between the lovers needs to be cut in half. And perhaps the word “sexy” should be used more sparingly, given the novel’s historical setting.

In the spirit of “being nice,” write how you enjoyed the archery scenes and many of the supporting characters, which is true—you’re a sucker for a precocious little sister or an unexpectedly-progressive dowager. Swaddle your critiques in qualifiers, padding each sentence with a “perhaps” or a “sometimes.” Before hitting send, add, “Improvements could be made to the relationship’s pace. It develops a little too quickly.”

…

This represents an upgrade from your first days at the office, in which you wrestled with the typewriter, played gopher, pushed paper. You can’t believe this office has a typewriter. Your tour of the extensive and color-coded files (“Interns often find it helpful to draw a map,” your supervisor suggests) ends at the intern desk, where the slush pile of unsolicited queries is contained—for now—in the large drawer to your left. You flick through the envelopes, which are stamped with earnestly excessive postage. The oldest has languished for a month and a half. This pleases your supervisor. “We’re pretty ahead!” she remarks cheerfully.

Your job is to bump the hopefuls from this particular ring of purgatory, sorting them into Yeses, Nos, and Maybes. Your boss will check your work, but she provides some helpful guidelines: historical fiction should be pegged to immediately recognizable figures and events, or else it doesn’t sell. A thriller should elevate your heart-rate by the tenth or fifteenth page, or else it doesn’t sell. Nonfiction should have a platformed author, or else it doesn’t sell. Literary fiction doesn’t sell.

What does sell is romance, approximately $1.368 billion of it per year.

Interns generally come up with a 40:60 ratio of nos to yeses and maybes, your supervisor informs you, but eventually your ratio should shift to 70:30. Smile. She underestimates your ruthlessness.

For your part, you have underestimated the lengths to which people will go to secure an agent: the sample chapters painstakingly bound in plastic covers, the mix CDs and original soundtracks, the occasional, perplexing headshot. Your supervisor sees fit to mention that the agency doesn’t accept anyone who sends hand-written letters. Or anyone in prison. These additional rules eliminate more manila than you’d expect.

…

The next manuscript lands you back in bodice-ripping England, with another eligible earl, another ravishing young debutante. Anna Karenina is deadweight in your backpack on your daily speed-walk through Midtown.

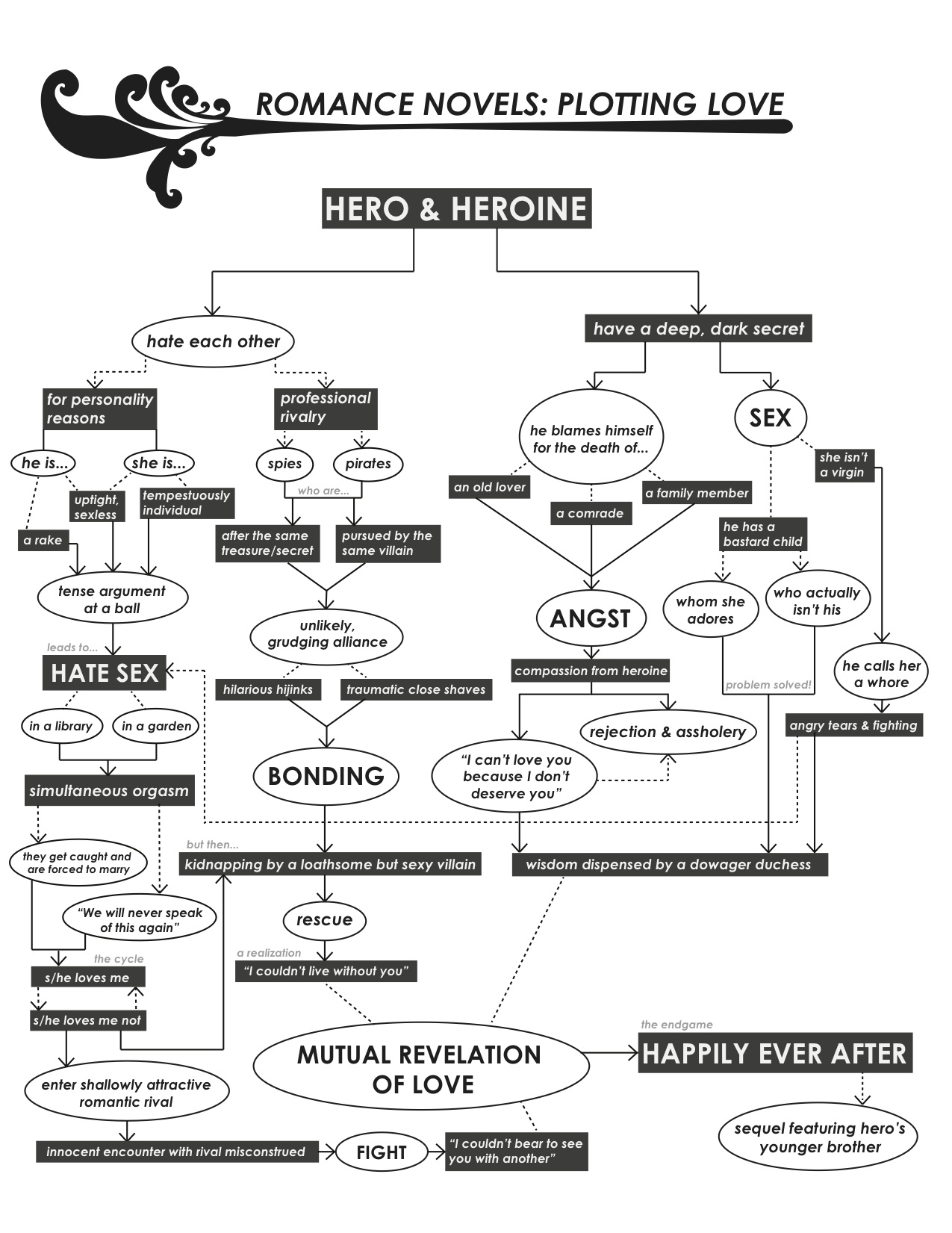

Over time you gather a vast lexicon of the tics of Romance, but inexplicably, you’re immune to irritation. As you encounter them, you greet these clichés like old friends: childhood friends-turned-lovers, ladies compromised on balconies, yawning gambling debts, deranged kidnappings in the final act. Eventually you graduate to other worlds: Gilded Age, steampunk, super-hero. A nonfiction proposal and mystery cross your desk, but do not break your stride.

This is how the genre does so well—its readers want comfort, not novelty, and they will return again and again for the minute yet endless variations which each story can offer. There’s a subgenre for everyone, each a thriving fiefdom unto itself: urban fantasy and paranormal, suspense and small-town, inspirational (i.e., Christian) and erotic, historical and “ethnic.” There are even series centered on characters’ professions, like “Harlequin Medical Romance” or “Stories set in the World of NASCAR.” Romances can be consumed in fistfuls, like M&Ms, a habit enabled by the e-reader, which razed the biggest barriers to consumption: embarrassment and difficulty of access. These books are priced to entice the impulse buyer: $5.99, $4.99, with a novella tossed in for free. In the digital age, no one has to wait for another fix. You are getting the raw stuff.

…

Abruptly, you’re given a “special project”: a full manuscript that had been sitting in the inbox for a few months. Not a romance.

It’s good. The beginning is messy. Its seams show. The scenes are layered in a way that makes the pace groan forward by inches. But the characters are alive, and for the first time that summer, you sit on the train and re-read a line, just to feel it hit you again. It’s always difficult to articulate why you like a given piece of art; it’s even harder when it’s not quite art yet. People talk a lot about love, but liking something is its own weirdly strong feeling. You think this story will speak to someone. You think it speaks to you.

You heartily recommend it for acceptance.

Despite yourself, you’re a little in love.

…

If the publishing industry has been gutted, no one has told the writers. Each day brings a fresh batch of query letters to add to the slush. The writers introduce themselves and their writing backgrounds, tell you about their families and hobbies. A speed date where you have all the power.

Occasionally it may occur to you—briefly, horrifyingly—that you are more likely to take a chance on a sweet query than any of the real live human romantic prospects of your recent past. Ignore this.

Doggedly chip at the slush pile. It’s cathartic to clear out the desk, though you hold out hope that you’ll find something. Fish out a few proposals that look promising, nervously turning them over for inspection. Your supervisor rifles through, looking deeply unimpressed, though she says she’ll take a look at them soon.

“From now on,” she adds, “You can just send out your rejections. You don’t have to run them by me. All of your nos have been spot-on.”

Not so much with your yeses, but damned if you will stop trying. In the last week, you feel like you’ve hit a vein of gold. In the slush pile, you pull out three or four decent options: a memoir or two, a dystopian road novel, a New England woman’s fiction which, if you squint at it right, could conceivably be an Oprah’s Book Club pick. You are willing to overlook almost all faults. Their mistakes will be caught by the agent, or in editorial. Anything can be fixed. You are desperate for variety.

Yet in your heart, you know that if you saw these books in a bookshop, you can’t imagine you’d look twice. Wonder if, in the publishing world, you’ve become a whore with a heart of gold.

…

In an e-mail, a writer friend complains about some “love story for adults” she’s been duped into trying, a bestseller far more up-market than anything resting on your bedside table. She jokes, “Do you ever get that fear that if you read enough bad prose it’ll get trapped in your ear, and you’ll start writing it? Horror of horrors!”

Actually, you fear that you’ve forgotten how to read. After four semesters of high-fiber, nutrient-dense hits of the literary canon, you had become a vocal advocate for cultural omnivorism. These days, you feel your slush diet eroding your palate, your appetite, your metabolism.

Painfully bore through your great Russian novel, never gaining enough momentum to absorb the text. You begin to resent the physical heaviness of it, just as an object. When it falls off your lap on the train, you wake with a start. Picking it up, imagine typing up a few recommendations for Tolstoy, in that peculiarly sunny voice you’ve come to own. “While I found the characters sympathetic (particularly Anna and Kitty!) the novel has a few major structural problems with regards to its pace. While the interrelated cast of characters is balanced deftly, the prose takes lengthy detours into farming practices and party voting procedures, and these grow somewhat dry at times. The book might also benefit from more fleshed-out and explicit scenes between Anna and Vronsky. As it stands, the interlude marked by the ellipse in Part One feels jarring and dissatisfying, especially since such ellipses do not occur elsewhere in the book. It feels accidental, then coy.”

Consider throwing yourself off the Aberdeen-Matawan platform as penance.

…

The manuscript you were rooting for is nixed. With terrible kindness, your supervisor deems the novel unfixable: too much narrative distance, confusing chronology. You’re not sure what “narrative distance” means, but you swallow her explanation.

It’s a heart-breaker. She asks that you draft a form rejection, with a nice note to say that the agency would be happy to look at future work, the agency equivalent of “I don’t think this will work out, but I hope we can still be friends.”

On the 6:31 p.m. express out of Penn Station, entertain yourself by spying on your fellow passengers. This is the summer of Fifty Shades of Grey. You are impressed by any novel that threatens to unseat Angry Birds as the commuter’s diversion of choice. They can’t hide from you, these young women folding back the paper cover, the businessmen hunched surreptitiously over their Kindles.

Like everyone else, develop opinions on the book without having actually read it—its deadening prose, its Cinderella story so weirdly evacuated of eroticism—but your feelings lack the same bile. Honestly, you’re just a little bit dazzled. Who are you to argue with a book that has earned $50 million for its author in six months? The people have spoken. It sells. And it sells film rights, soundtracks, and condoms.

Good romance novels are all alike; every bad romance novel is bad in its own way. Keep reading the manuscripts as they roll in. You have become a mechanic of baroque Rube Goldberg machines, the characters spinning like sawtooth gears and extraneous plots rattling cheerfully, waiting for your tightening wrench, a little extra weight. You work with what you have. It soothes you to take a look under the hood and make it right, so that after an hour or so you can step back and say, “it ain’t pretty, but it’ll get you from Point A to Point B.”

The end of the summer leaves you ambivalent about the book business. After months on the inside, you have come to understand the alienation that aspiring writers feel from the publishing industry — their sense that the gatekeepers’ choices are so inscrutable and idiosyncratic that they’re essentially arbitrary. You made your choices, guided by well-meaning mentors, according to prevailing industry logic. But you know the imperative to sell lucrative schlock in order to finance the elusive gem would eventually grind you down.

Finish your Tolstoy, which ends, to your surprise, not with Anna in the wheels but Levin under the stars. Don’t read at all for a few days.