Squeezed between Ivy Noodle and Tomatillo on Elm Street, Kathryn Redford’s apartment features less conventional cuisine than either restaurant. Redford, 27, is the founder of Ofbug, a six-month-old start-up dedicated to the production and promotion of insects as animal feed. The bugs live in a few plastic IKEA boxes in the corner of her living room and die a few weeks later in her freezer, after which Redford dries and processes them into food.

Squeezed between Ivy Noodle and Tomatillo on Elm Street, Kathryn Redford’s apartment features less conventional cuisine than either restaurant. Redford, 27, is the founder of Ofbug, a six-month-old start-up dedicated to the production and promotion of insects as animal feed. The bugs live in a few plastic IKEA boxes in the corner of her living room and die a few weeks later in her freezer, after which Redford dries and processes them into food.

“I really wanted to make a product that didn’t look like an insect and introduce it to the Western world,” Redford said. “We wouldn’t eat an insect if it looked like an insect. Nor would we eat a cow if it looked like a cow.”

Redford ate her first bug–a spider–in kindergarten. Another child who took pleasure in slaughtering spiders refused to stop killing them unless Redford ate one, so she did. Now she is working to develop insect-based animal feed, and eventually human food, and in the process has become part of an expanding network of individuals around the world who are working to incorporate bugs into the Western diet.

According to a website titled “Entomophagy”—the scientific name for human consumption of bugs—twenty-four restaurants in the United States list insects on their menus. Though none are listed in Connecticut, five such eateries are listed in New York, including two frozen yogurt shops.

The idea of edible insects for the Western world has also caught the attention of the United Nations. A March 2012 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) report developed an action plan to move the issue higher on the international agenda. The report estimates that eighty percent of humans around the world already include insects in their diets.

Afton Halloran, who works with the FAO Edible Insect Program, explained that producing breeding insects for animal feed is less energy-intensive than producing food crops. Bugs can be bred and mass-produced in short periods of time, and they emit fewer greenhouse gases.

Redford and her husband, Paul Froese SOM ‘13, who studies at the Yale School of Management, share the apartment with the bugs, a pet hedgehog named Fangu, and various remnants of other animals: snakeskin and a coyote bone sit in glass vials on a side table next to a dried deer leg. When I visited the apartment in late January, only one of the bugs was alive. It moved lethargically across a bit of carrot that Redford had added to a glass of oatmeal. The bug was the sole survivor of a cannibalistic melee in which recently metamorphosed pupae had gone after one another.

Currently, Redford raises mealworms and crickets (an initial attempt to breed silkworms ended when a whiff of Paul’s cologne led to their untimely death). The mealworm beetles grow in three plastic boxes, each corresponding to one of three life stages: larvae, pupae, and beetle. The larvae, which we would recognize as mealworms, are what Redford uses for feed, letting some grow to beetles for breeding. An entire generation grows and dies over the course of three weeks. Next to the larvae sit two plastic boxes for the crickets, one specifically for breeding.

When they’re ready, the mealworms and crickets go in the freezer. This allows them something like a natural death before Redford dries the bugs in a standard kitchen dehydrator and then, sometimes, pulverizes them in a coffee grounder. Freezing minimizes pain, she said. Even so, she paused before she put in her first batch.

“Oh my gosh, I’m going to kill thousands of lives right now,” she remembers thinking. “I don’t take pleasure in killing them or anything like that. I definitely have a conscience about it. My focus is on the greater goal here.”

Gregory Sewitz, a senior at Brown, has a similar goal but different approach. He is also concerned about food security and nutrition, and is developing an insect-based snack for human customers.

“You have to create the market for eating crickets,” Sewitz said. “Protein bars are the best way in.” Sewitz plans to market a protein bar that hides the insect’s taste and texture, one that would look and taste like other major brands such as Cliff Bar and ProBar.

While chickens may have no objection to eating bugs, humans, specifically those in Western culture, are a different story.

“A lot of the stigma has to do with the look of insects,” Halloran said. “We’re naturally inclined to either squish the insect or say, yuck, that’s gross.” But we’ve gotten used to eating strange animals before, she added. Shrimp and lobsters, which resemble insects, used to be low-expense foods for working people. Now both are luxury items.

“We’ve been eating our way around the true insect,” she said.

Even Redford experiences a visceral discomfort to eating certain kinds of bugs.

“I definitely–this is super hypocritical–I definitely don’t like legs and stuff like that on insects,” Redford said. “They’re twine-y, almost.”

She prefers mealworms, she said. “You can just pop them in your mouth when they’re dehydrated.” Scorpions and tarantulas are a no-go, but not because of the armored exoskeletons or hairy legs.

“I love them too much,” Redford said.

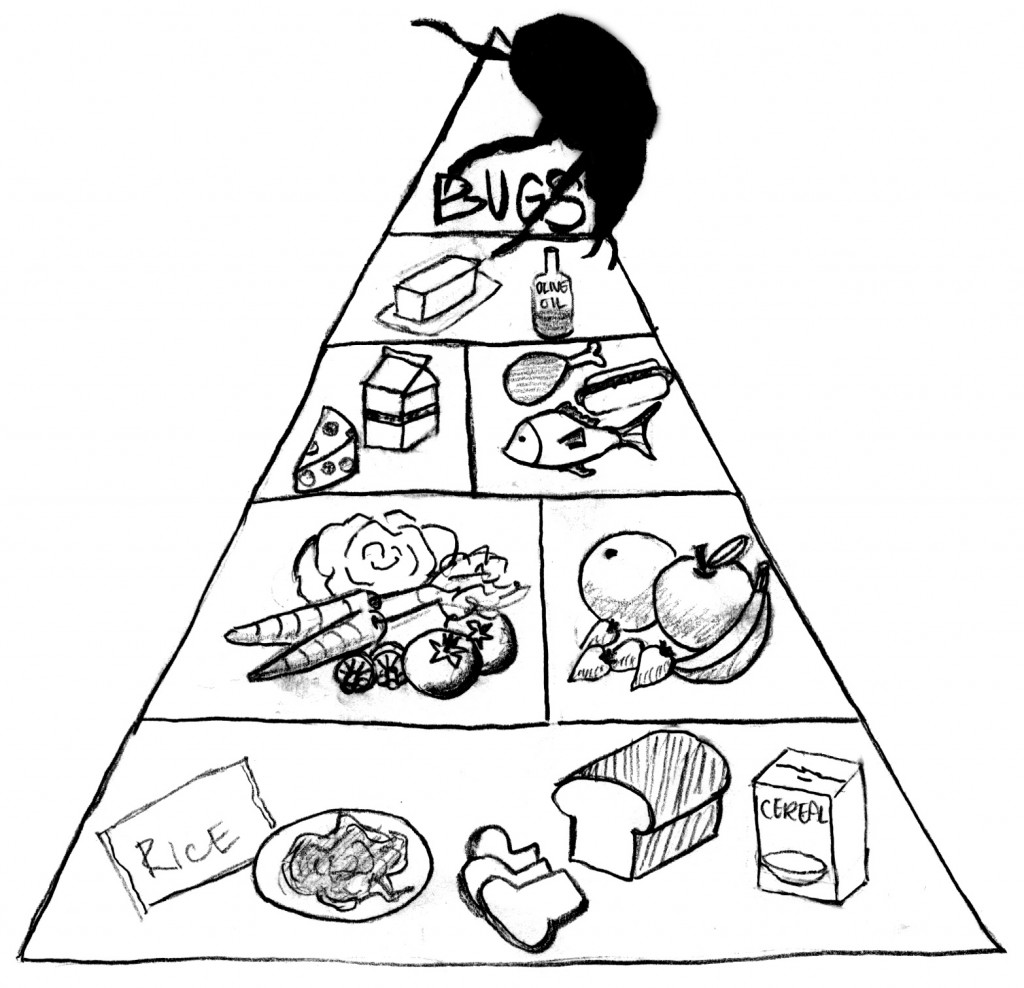

Illustration by Katharine Konietzko