Officer Mike Pepe is cruising around the Dwight-Kensington neighborhood when he gets the call. Two women, the dispatcher tells him, are sitting on a park bench at a nearby elementary school playground. They’re staring into space while a toddler lies screaming on the ground.

Pepe, a four-year veteran of the New Haven Police Department, quickly heads to the scene. He finds the two women, perhaps in their thirties, their eyes bloodshot, ignoring the baby girl sobbing desperately before them.

Pepe climbs out of his cruiser. I follow about ten feet behind, wrapping myself tightly in a thick knit sweater. It is an unusually frigid afternoon for late April, too cold, I think, for a mother to bring her child to the park. The baby’s coat looks thin and shabby, not thick enough to shield her from the wind.

Another officer, Sgt. Mario Francia, arrives on the scene. As he and Officer Pepe approach, one of the women spots him and finally acknowledges the baby. “What happened, mama?” she slurs, not moving to scoop the child off the ground. Her companion remains too catatonic to react.

Pepe approaches the women, a kind look of concern on his face. It is immediately clear to him that both are high on something, perhaps PCP. “Hey, how are you doin’?” Pepe calls out, cautiously approaching the two women. “What’s your name?”

Again, neither woman responds. After a long pause, the one who had cooed at the baby a moment earlier utters, “Katina.” The second woman still does not speak; she cannot speak.

“What happened to her?” Pepe asks casually, gesturing at the child on the ground. “Did she fall or somethin’, guys?”

“She aright,” Katina responds in a daze, the baby’s sobs growing louder.

Pepe picks up the baby and starts bouncing her. The baby’s diaper, he later tells me, feels as though it is reaching the point of explosion. “That’s my baby!” Katina raises her voice. “Why you actin’ like this? I’m just chillin’.”

“You seem, uh, very out of it,” he explains calmly, asking her to remain seated. “What’d you do today?” No response. “You do drugs? You drink? Any alcohol or somethin’?”

Pepe is calm and nonjudgmental. He continues for several more minutes, cajoling and soothing the women to the best of his ability, until an ambulance and a police cruiser arrive to take the two women away. Katina does not want to go, yelling that she has done nothing worthy of arrest. But she succumbs to her handcuffs and her companion, still impassive, is loaded onto a stretcher to be taken to the emergency room. The baby’s godmother, who lives nearby, takes the child home.

“I think we handled that situation the best we could,” Pepe tells me back in the cruiser. But, several years ago, Pepe adds, he might have approached the scene differently. He might have expressed his frustration at the two women; after all, they had both willingly taken drugs, endangering the baby. Had he acted on these emotions, Pepe might have yelled at the women out of frustration, perhaps handcuffing Katina more aggressively. He could have decided to arrest both women, rather than sending one to the hospital. But Pepe now understands that when an officer rough-handles someone with mental illness, his actions can exacerbate the situation.

These days, Pepe responds differently to calls like these, thanks to a program in Connecticut designed to teach police officers how to recognize and work with individuals who are mentally ill. The program, run by a nonprofit organization called the Connecticut Alliance to Benefit Law Enforcement, or CABLE, has employed the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model since 2003. The core purpose of CIT is to intertwine the realms of law enforcement and mental healthcare—two fields that, until recently, have remained resolutely separate.

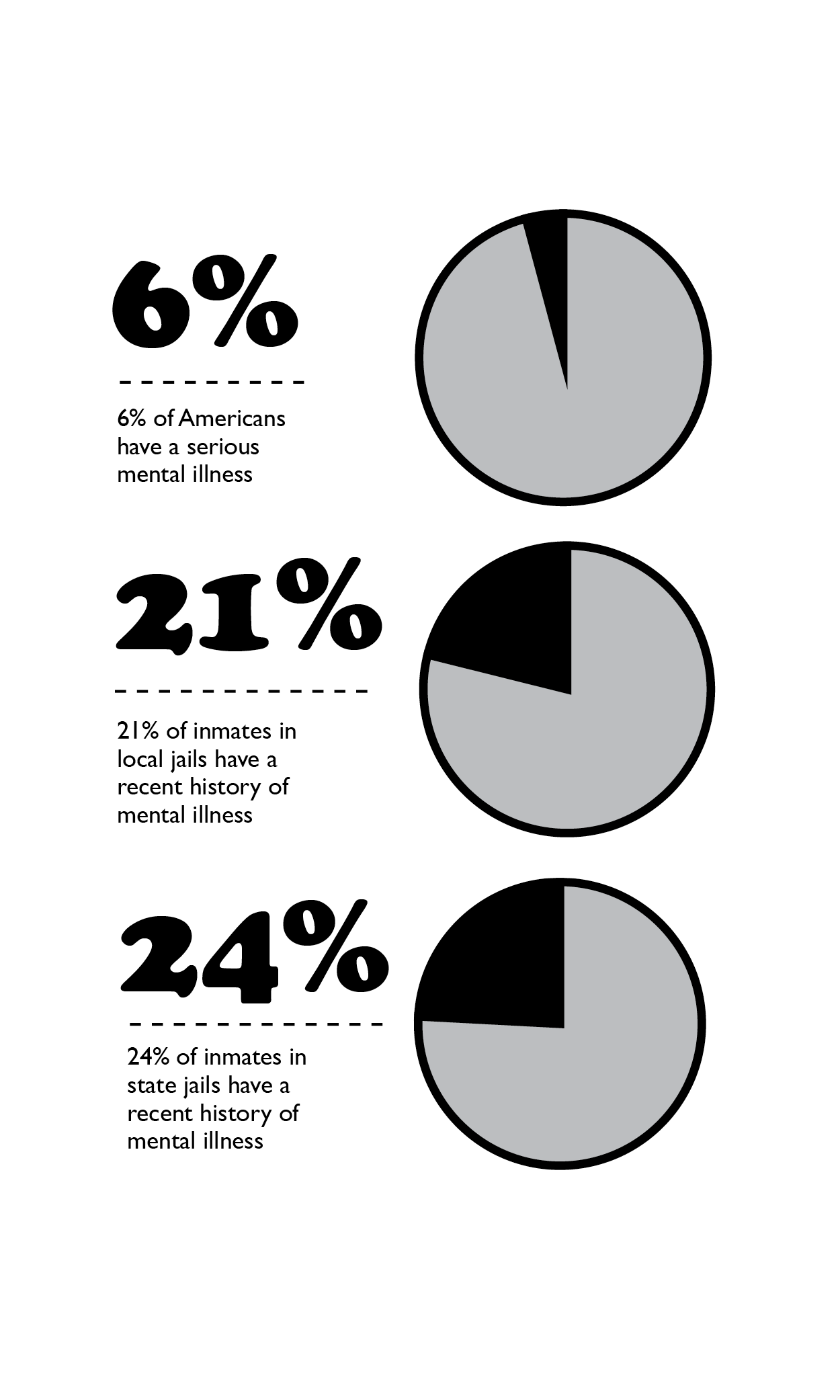

Decades ago, such a division made sense: A vast majority of Americans with a diagnosable mental illness lived out their lives confined inside state hospitals or other institutions. In 1955, at the peak of “institutionalization,” as the practice is now known, these facilities contained 339 beds per every 100,000 Americans. But from the late fifties through the early eighties, patients were discharged from hospitals and returned to their communities. The shift was partially intentional: Advocates of the plan believed that these individuals would live more fulfilling lives integrated into normal society. New psychiatric drugs, which were emerging on the market at the same time, were thought effective enough to quiet anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and psychosis—many of the most severe syndromes that had originally forced states to institutionalize individuals. Civil commitment laws around the nation were reformed so that only the most severely mentally ill—those who posed an immediate threat to themselves or to others—could be hospitalized against their will.

At the same time, state budgets were shrinking, and state hospitals were a prime target for cuts. By the turn of the century, the number of beds per 100,000 people had fallen to twenty. Dwindling funds, moreover, meant that states were not financially equipped to build the comprehensive, community-based mental healthcare systems necessary to care for people who had been discharged from hospitals.

Connecticut has one of the nation’s most well-funded and well-managed mental healthcare systems. Even so, says Madelon Baranoski, an associate professor of Law and Psychiatry at Yale’s School of Medicine who teaches a module of CABLE’s CIT training course, not enough services have sprung up to provide the care once offered in hospitals. Consequently, many people with severe mental illness are left to their own devices, encountering mental health professionals only in times of crisis. Public health officials liken this neglect to only treating a patient with heart disease once he has suffered a heart attack—ignoring a serious problem until it becomes a crisis.

***

Nearly every day, police departments across Connecticut receive phone calls from families where one member with mental illness is in crisis; the callers fear either for the ill family member’s safety or for their own. In addition, in the state’s urban centers—cities like Hartford, Bridgeport, and New Haven—many homeless residents suffer from mental illness, wandering the city streets talking to themselves, disconnected from any available mental health resources. New Haven, in particular, has an especially large population of people with mental illness, largely because of its Yale-affiliated hospitals and its abundance of group-living homes.

Sgt. Chris McKee, an officer with the Windsor Police Department who has taught CIT courses for four years, says that, in general, police are not adequately taught to recognize signs of mental illness. “It’s our job to get a scene safe,” he says. “But we can’t run into a house with a bipolar person and put our hands on their shoulders and force them to sit down. They are going to pace. They are going to get up and fidget and feel anxious. When the police tell them to do something, they don’t always listen.” In cases like these, McKee says, officers may arrest—or even shoot—the individual because they do not recognize his or her uncooperative behavior as a manifestation of mental illness.

CIT training attempts to prevent these situations by teaching police officers to recognize symptoms of mental illness and to use techniques that will calm people in crisis. What you need, Pepe says, is sensitivity: sensitivity in what tone you take, sensitivity in which words you choose, sensitivity in your physical interactions. Such an approach, proponents of CIT hope, reduces the risk of injury to both police officers and individuals with mental illness, diverting those individuals to mental health treatment instead of jail.

“Police have learned that the command presence that they use—usually with the bad guy or the robber—that command presence, yelling, being really forceful, doesn’t work with people with mental illness,” says Louise Pyers, the founder and executive director of CABLE. “It makes it worse. So if they can identify, ‘Here is someone who clearly has a mental illness,’ they can come in a lot slower, be a lot less threatening, speak softly, ask questions in a non-threatening way.”

Pepe, a burly, dark-haired teddy bear of a man, is the perfect guy for the job. He can be gruff when a situation warrants it, but, for the most part, he is soft-spoken and jovial. As we drive in his cruiser, he listens to pop music and chats about his two kids. His speech, tinged with a mild Boston accent, is frequently punctuated with short, loud belly laughs. When we pass by other officers, he rolls down his window and shouts their nicknames. Though he wears a gun on his hip, and he has warned me that violence could come around any corner, I feel strangely safe sitting by his side. Perhaps it’s the unending banter. “I like talking to people,” he tells me over the whirs and beeps from the cruiser’s radio. “I have no problem talking to pretty much anyone.” (That’s good, because I’ve been in his passenger seat for close to seven hours.)

Pepe tells me that his CIT training, which he completed two years ago, has primarily taught him to slow down and use conversation as a way of making others feel comfortable. “You get sent to a call like, ‘guy standing in the middle of the street yellin’ and screamin’,’ you have no idea—you don’t want to put yourself in a situation to have that yelling and screaming become a fight between you and him.”

“That’s where I think some of the CIT stuff comes out,” he continues. “‘What’s going on, how are ya’, what’s your name, where do you live?’ You’re not gonna yell and scream at him, ‘Get out of the road! I’m gonna lock ya up!’” The latter kind of interaction, he says, can even act as a trigger for mental health crises.

Once Pepe has won someone over, it’s easier to convince him or her to go to the hospital without putting up a fight. After talking for long enough, some people even choose to go voluntarily. In cases where Pepe has been called to mediate, but decides that hospitalization is not necessary, he can pass the individual’s name along to New Haven’s CIT clinician, based at the Connecticut Mental Health Center. She can then follow up to connect the individual with mental health services.

Proponents of the CIT model emphasize that it expands a police officer’s range of options. Pepe says that, in some situations, he doesn’t have much choice. When he is called to a situation involving domestic violence, for example, Connecticut law requires him to make an arrest. But CIT teaches officers, in the words of Amy Watson, an associate professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Jane Addams College of Social Work, “not to arrest for stupid stuff”—charges like “disorderly conduct,” when a person’s symptoms cause them to behave in disruptive, but not necessarily criminal, ways.

That doesn’t let people with mental illness off the hook for all crimes. “Certainly,” Watson tells me, “if you have a mental illness, it doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t be arrested if you steal something. But if your voices are telling you to steal something, maybe arrest isn’t the most productive avenue.”

***

In 1988, police in Memphis, Tennessee shot a 27-year-old man named Joseph Dewayne Robinson. Robinson was in the midst of a mental health crisis at the time, cutting himself with a knife and threatening suicide. The officers repeatedly ordered him to drop the knife, but he only grew more agitated, moving toward the officers. They shot him eight times.

A public outcry surrounding Robinson’s death led the Memphis Police Department and researchers at the University of Memphis to collaborate on a program that would teach officers how to interact more humanely with the mentally ill. Before CIT, patrol officers used to ask separate mental health experts to join them on calls requiring psychiatric training. But each police department’s fleet of mental health professionals was small—if they could afford one at all.

CIT helps rank-and-file members to add these skills to their repertoire. (At least 2,600 local departments currently have CIT-trained officers on the ground, according to the University of Memphis’s estimate.) In New Haven, elements of the CIT model have been incorporated into the initial training that all patrol officers receive, and the department is attempting to send as many officers as it can afford to CABLE’s training courses. “I think it’s just an extra tool you use when you’re on the street,” Pepe says. “I think it’s for everyone.”

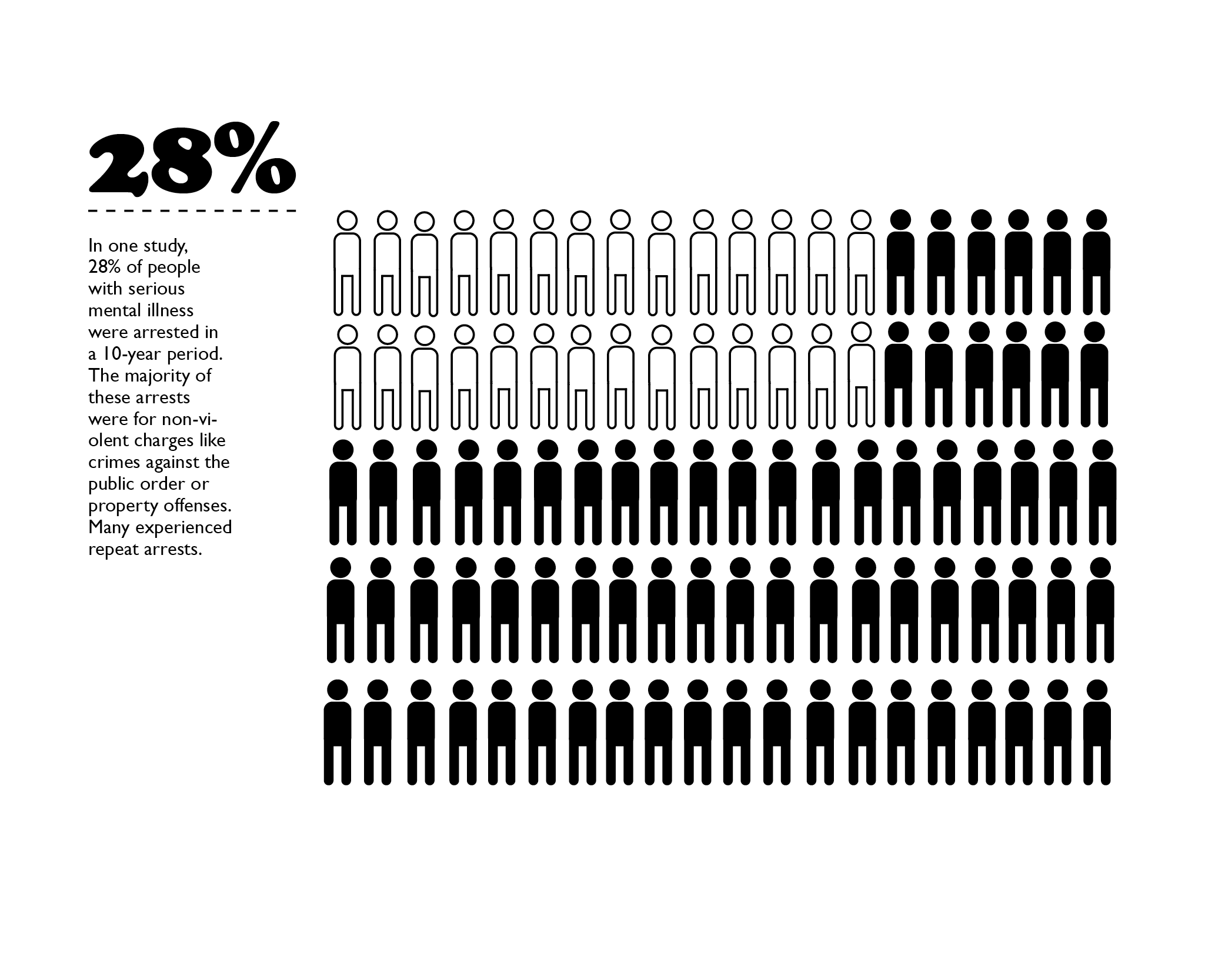

The numbers prove that Pepe’s success in the scene I witnessed wasn’t just an anomaly. In 2002, Dr. Randy Dupont, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Memphis, oversaw a project that tracked 1,200 individuals with serious mental illnesses who engaged with law enforcement officials during that year, to gauge CIT’s effectiveness in Memphis. Six hundred had interacted with CIT-trained officers, while another six hundred had encountered untrained officers. Dupont and his colleagues only tracked individuals who were directly connected to community services and individuals who were sent to jail but soon diverted back into community services, so as Dupont puts it, “their paths converged very quickly.” Not only did the researchers find that CIT-trained officers were much less likely to send mentally ill individuals to jail than their untrained counterparts, they also found that mentally ill individuals who had briefly been exposed to the jail environment were less likely to see an improvement in their psychiatric symptoms three months later, less likely to remain in treatment, and more likely to be rearrested. Dupont’s research, along with scores of other studies coming out of Memphis, encouraged other cities and states to consider the CIT model.

***

Just as the death of Joseph Dewayne Robinson spurred unprecedented collaboration between the police department and the mental health system in Memphis, an unexpected run-in with law enforcement was the catalyst that led Pyers to bring the Memphis model to Connecticut. In 1997, her son Seth, whose name has been changed in this story, was a 19-year-old engineering student at a university in New Jersey. Soon after entering college, Seth was diagnosed with Major Depressive Disorder and prescribed anti-depressants. Every month, he would drive up to his hometown in central Connecticut for a routine visit with his psychiatrist. One morning that spring, Pyers was awoken early by a phone call. An officer from the local police department informed her that Seth had been shot in the stomach by an officer in the middle of the night.

Pyers was confused: Her son had come home for a doctor’s appointment just several weeks prior, and he was not due back home for several more. Seth was no longer a minor, so his psychiatrist could not have informed Pyers that her son had recently taken an emotional nosedive. Seth had attempted to take his own life by swallowing an entire bottle of over-the-counter painkillers. When that effort failed—“All it did was make him sick,” Pyers recalls—he began thinking about other, more fail-proof methods.

The evening before Pyers received the phone call, Seth had decided his surest option would be to use a gun. But he did not own one, and neither, he knew, did his parents. Then it occurred to him: Police carry guns.

So that night, he clambered into his car, sped to Connecticut, and led several police officers on a car chase. In an effort to end the encounter quickly, he rear-ended one of the cop cars. The officer Seth had rammed got out of his car, and Seth ran toward him shouting, “You better shoot me, or I’ll kill you!”

Pyers still remembers her son’s remorse upon waking from emergency surgery hours later. “He remembered looking into the officer’s face and said, ‘I brought this man into my nightmare, and I shouldn’t have done that.’”

Pyers, who had already been working in the mental health field, soon realized that her son required a case manager to oversee his treatment, so she quit her job to take care of him full-time. She could not help but wonder: How many others had come before her son, using police officers as the instrument in their own suicides?

She began researching the issue, and in August of 2001, she published her findings in the FBI National Academy magazine. One in four officer shootings, she concluded, are purposefully provoked by the victim—a phenomenon known as “suicide by cop.”

Pyers initially founded CABLE as a research and education non-profit to support further study on suicide by cop. But soon after she published her initial findings, she got a call from Captain Ken Edwards of the New London Police Department. “I saw your information on suicide by cop,” she recalls him saying. “He said, ‘We’re doing a program here called crisis intervention training. Do you want to see it in action?’” Pyers had heard about the CIT program in Memphis, and Edwards told her that his department had gone to Tennessee to learn how the program worked.

When she went to New London to attend a CIT training session, she realized for the first time that the scope of perilous interactions between law enforcement and people with mental illness extended far beyond suicide by cop. But she also remembers feeling surprised by the passion of the officers at the training, all of whom had volunteered to learn more about mental illness. It was the conversations with these officers, she says, that helped her understand the full scope of the problem.

After the training, she approached Edwards and asked him if he would help her implement the program statewide. In 2004, CABLE, with Edwards’ help, won a grant from the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DMHAS) that would enable Pyers to do just that. Now, the state pays CABLE about $65,000 per year to run five weeklong CIT trainings. It also offers each police department a $1,500 stipend per officer it sends to be trained. DMHAS issues about $20,000 in training stipends per year, according to Loel Meckel, the assistant director of DMHAS’s Division of Forensic Services.

The training, which spans five eight-hour days, includes educational lectures on different types of mental illness, role-plays to practice de-escalation skills, and a simulation of what it might feel like to hallucinate. For a more personal perspective, Pyers also invites the officer involved in her son’s incident to speak to the training attendees; he tells his story, and her son tells his own in a pre-recorded video.

Baranoski, the Yale professor of psychiatry, teaches what she calls “Mental Health 101” on the first day of each training. She opens the module with basic science: She introduces officers to several broad classes of mental illness and their associated symptoms. She explains how brain chemistry causes disturbances in thought. But, she always tells the officers, it is much more important for them to understand how to handle an individual in crisis than to recognize the specific illness plaguing him or her.

“The diagnosis doesn’t matter,” she explains. “What matters is the state that the person is in when the police gets involved. They’re overwhelmed. Their usual behavior and their usual coping methods are not working. So how do you manage that? How do you get people to the right level of treatment?”

During the eight-hour evening shift on which I accompany Pepe, he receives no “Signal 90” calls—NHPD code for a situation involving a psychiatric crisis. (The call involving the two women is technically classified as a “Signal 98,” a drug-related situation.) But Pepe tells me that this is rare. It is not uncommon for an officer to take one or two Signal 90’s per shift. And even situations that are not technically psychiatric crises—drug-related crises, for example—allow him to use some of the skills that he learned in CIT training.

Each situation requires its own set of strategies, he says, but at the core of his approach is an attempt to understand what sort of help the mentally ill person actually needs.

“They might not know what’s goin’ on. So you have to slowly try to reel them in, to get them whatever help they need,” Pepe says. “Maybe they want medication. Maybe, at the end of the day, maybe the only reason they called you is because they’re just unsatisfied with where they live. They wanna go somewhere else, but they don’t know what to do.”

Pepe drives me past the Park Street Inn, one of the group-living homes he is sometimes called to. A converted brownstone walk-up that dates back to the early 1900s, the three-story home currently houses 15 residents with a range of mental health conditions and substance abuse issues. Most often when Pepe comes here, he has been summoned by one of the residents. Their complaints, he explains, are often things like “This person is talking to me mean” or “This person put his hands on me.” Though two on-duty staff members manage the home at all times, the residents are granted a large measure of independence, and often they are the ones making the 911 calls. Still, Pepe says, he is not sure why they turn to the police.

Pepe drives me past the Park Street Inn, one of the group-living homes he is sometimes called to. A converted brownstone walk-up that dates back to the early 1900s, the three-story home currently houses 15 residents with a range of mental health conditions and substance abuse issues. Most often when Pepe comes here, he has been summoned by one of the residents. Their complaints, he explains, are often things like “This person is talking to me mean” or “This person put his hands on me.” Though two on-duty staff members manage the home at all times, the residents are granted a large measure of independence, and often they are the ones making the 911 calls. Still, Pepe says, he is not sure why they turn to the police.

“Maybe we’re just a different avenue,” he speculates. “They know, maybe we’ll just get them to the hospital a little quicker. I don’t know what they know. I think they just know 911.”

A few days after accompanying Pepe on his shift, I go back to visit the Park Street Inn. The house is managed by a team of social workers, but they work mainly in offices at the front of the home, on the first floor. Residents mill about the rest of the cramped space, wandering down to the kitchen, or gathering to watch television on a large flat-screen in the home’s cozy dining room. Though the residents appear amicable when I visit, Dan Collins, one of the Park Street Inn’s program directors, tells me they occasionally clash or make “very poor decisions.” When one resident threatens the safety or well-being of another resident or staff member, he says, “Yeah, they’ll see an officer in blue.”

But in the thirty or so years he has worked in such environments, Collins says, he has never seen officers interact with people who have emotional difficulties as well as Pepe and his colleagues do.

“Law enforcement’s understanding and skills at engaging our program members has just been getting better with each passing year,” he says. He rattles off the names of several officers, Mike Pepe’s among them, who have been particularly effective. “They are more at ease. And they’re more comfortable and skilled at making a connection with the person.”

For example, he says, an officer might try to move a conversation into a more comfortable space. We are standing in the foyer of the home, a tiny round room with doors and hallways shooting off in every direction and a large fish tank at its center. He gestures around us. “You don’t want an explosive situation happening in this confined area,” he tells me. We walk down one of the hallways to the dining room, which has two red high-backed wing chairs in one corner. “So the officer might say, ‘Hey, would you be comfortable going to sit in the dining room?’” With that simple change, a CIT officer could solve a problem another officer might not even have noticed.

***

You smell like shit.’ ‘You stepped in dog shit.’ ‘You smell like poop.’ ‘You stepped in poop.’”

Pepe remembers the relentless voices well. He was trying to make a purchase and count out exact change. But his headset was playing a looping recording of three or four voices, speaking at different volumes, sometimes overlapping one another.

It was, he said, the part of his CIT training that most affected him. The exercise gives officers a sense of what someone on the street might be experiencing when they say, “The voices told me to do this.” Each officer heard a different set of voices, echoing a different set of insults. By the end of the exercise, none of them held the correct amount of money. “You are literally like looking at your shoe, like, ‘What, are you serious?’” he recalls. “You literally just got so confused with all the different things that were goin’ on.”

The experience “doesn’t make a social worker out of them by any means,” Pyers says. “But it really gives them insight. We teach them to recognize symptoms and say, ‘Oh, okay, this person is obviously hearing things that I’m not hearing right now, and that’s why they’re not responding.’”

CIT training has taught Pepe to be on the lookout for these symptoms in people on the street—not just in the people he encounters during calls. He says that as he drives, his head is always “on a swivel.” Many symptoms, he adds, are very easy to pick up. Patterns emerge: If someone is about to do something violent, he or she will often grind his or her teeth or tense his or her hands into fists. If someone is about to take off running, he or she will often first pull his or her pants higher on the waist. If someone is using drugs, he or she might be yelling in the street or sitting on a curb looking dazed.

But, Pepe emphasizes, he can quickly gain a much better understanding of what exactly is troubling someone just by chatting with them. “A majority of people are willing to talk. You just have to find that area that lets them open up.”

***

The research conducted on CIT training so far has proven promising but inconclusive. The 2002 Memphis study results were an early indication of the program’s potential, and the most recent studies suggest that CIT-trained officers arrest fewer people with mental illness and connect more with the mental health services they need. But existing data have not necessarily borne out the claim that CIT-trained officers use less force than their non-trained counterparts. Researchers have also not been able to determine whether a change in officers’ attitudes about mental illness significantly impacts their choices on the job.

“We have a reasonable level of confidence that [CIT training] can improve safety in encounters and probably increase the number of people that officers connect to services,” Watson, the University of Illinois professor, tells me. But, she cautions that these effects are only moderate. “A lot of officers who aren’t CIT-trained [already] do a fairly decent job—they learn what works.”

Pyers says that these findings mirror what she has observed in Connecticut so far. Officers are often required to arrest individuals with mental illness, especially if their crimes do not result directly from their symptoms. But, in the past decade, many others have been transported to the hospital for evaluations or connected to existing services instead of being charged for a crime their illness led them to commit. And, whereas officers may have arrested a person with mental illness on a petty crime like breach of peace before the CIT model was implemented, they are now more likely to understand that such an individual would be better off in treatment than in jail.

Meckel, the state official who oversees the DMHAS grants that fund CABLE’s CIT training courses, says that the state cannot truly measure the CIT model’s success because it lacks sufficient data to do so. “The police are not in the business of doing these cost-benefit analyses,” Meckel tells me. “We can think of a lot of numbers that would be useful to have, but it’s not what the police usually collect.” It might be helpful to know, for example, the number of people diverted from the criminal justice system and instead connected with mental health services. But even if the police were able to track the number of people diverted into public programs, they would not be able to track those who have private insurance and seek help through their own providers.

“The difficulty of all of this work is that you can’t say you prevented something,” Baranoski says. “You can collect data over time and say, ‘O.K., maybe we’ve made fewer arrests.’” But a lot of factors can influence that statistic.

Still, by Meckel’s estimation, funding CABLE’s CIT training program turns out to be cost-effective for the state. Assuming that CIT-trained officers prevent even a handful of individuals with mental illness from entering the criminal justice system, he says, the state is likely to save money. Even when the state pays for community-based services including psychiatrists, psychologists, case managers, rental subsidies, and hospitalizations, these costs add up to a fraction of the yearly cost of sending a person with severe mental illness to prison. For example, according to a 2008 study conducted by the Connecticut Office of Legislative Research, the cost per individual at the Garner Correctional Institution, a state prison in Newtown that housed mainly inmates with mental illness at the time of the study, was $85,000 per year. By contrast, the average cost of incarceration across the state stood at $40,000. And when an individual successfully reintegrates into his or her community, it also becomes more possible for that individual to find work, require less financial support, and contribute to the economy.

Cost effectiveness aside, Meckel believes the CIT model offers Connecticut other, intangible benefits. It has, in his judgment, helped people with mental illness come to trust the police. “We want people with serious mental illnesses—who are much more likely to be the victim than the perpetrator of a crime—we want them to feel comfortable going to the police,” Meckel says. “The more positive interactions they have with police officers, the more likely that is to happen.”

Watson takes a much more pessimistic view. No one, she says, says it’s a terrible idea to train officers in the principles of CIT. But, she adds, the fact that police must take on such a burden speaks to just how inadequate the American mental healthcare system has become.

“It’s a sad commentary on the state of mental health services. The police are stepping up to do it, because no one else will.”

Near the end of my ride with Officer Pepe, I ask him if he thinks CIT is effective. He remains silent for an uncharacteristically long time, contemplating his answer. Finally, he responds, “You know, I think about it all the time. I sent this guy to the hospital two weeks ago. Did it help? What’d it do? We don’t really know those things, you know? I mean, we kind of are just the first step.”

Michelle Hackman is a senior in Berkeley College.