I eased the SUV down a rough dirt road in northeastern Connecticut. My friend Téa, who sat in the passenger’s seat, peered into the shady woods ahead. She checked her phone to see if we were still headed in the right direction, but she didn’t have any service. Her hands fiddled with pens and papers, nervously sketching the twisted shapes of branches and leaves as we went around the next bend.

Then we were there, at Myers Forest, the largest of Yale’s seven forests. More specifically, we were at a campground that the Yale School of Forestry has used since 1919. We’d been driving around the forest for the last twenty minutes, weaving around groves of oak, hemlock, and pine. There’s a reason the trip was so long: Myers Forest is the largest piece of Yale property and one of the largest private forests in southern New England. On the drive over from I-84, we had traced the northern edge of the nearly eight thousand acres.

Trees lit by the fiery colors of fall rimmed the shallow lakes alongside the road. Ahead of us, the tangled woods opened into a small clearing. A few long, low wooden buildings—bunkhouses for when the forest has guests—were scattered across the field. They are mainly used in August when the first-year forestry students have orientation, or when the School of Forestry & Environmental Studies holds seminars. Last winter, for example, the School held a community lecture on tracking animals in forests. Professors also use the camp as a staging ground for the forty-five research projects currently being run at the forest. Some projects study the economics of forestry, looking for new ways to make conservation cheaper. One of many ecosystem projects focuses on the forest’s vernal pools, seasonal bodies of water that dictate the life cycle of salamanders.

Myers Forest is the largest piece of Yale property and one of the largest private forests in southern New England.

We tend to think of the wilderness as a place to be protected from the relentless economic forces of human expansion, lest it be lost forever. But Myers Forest stands as living evidence that this conventional wisdom is wrong. Myers is a place where we look under the hood of forests, examining the forces that drive their dynamism and resilience. Rather than loss, it tells a story of reclamation: its roots run deep through old farmland, across property abandoned during the age of westward expansion.

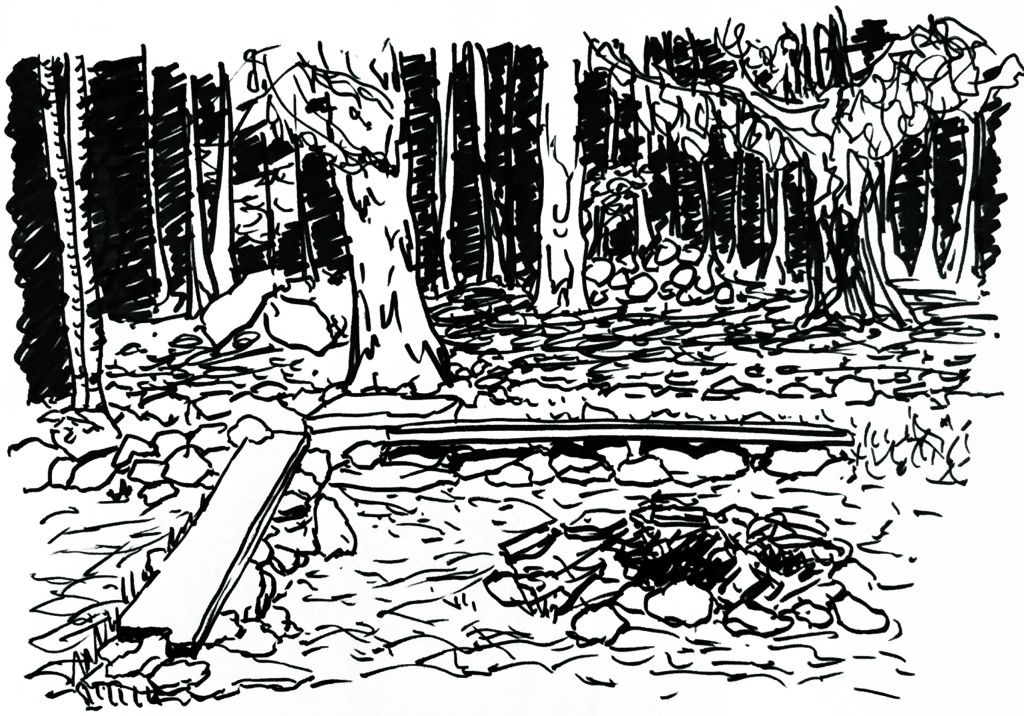

Only one hundred years ago, Myers Forest was a patchwork of farms in various states of decay. Now, vines cover the remnants of building foundations. Each rainy season, dirt and silt fill the old wells. To the trained eye, the composition of the forest contradicts its youth: it’s almost entirely filled with hardwood trees, like oak and maple, which can only grow after pine trees take root in empty fields and provide shade for seedlings.

But this reclamation has been guided and shaped by foresters, whose job it is to make forests environmentally and economically sustainable. They meticulously catalogue, tree by tree, to maximize the diversity and health of the species in the forest. Today, the forest is managed completely by Yale. It is the home of the Quiet Corner Initiative, a partnership that pairs the School of Forestry with local private landowners, natural resource managers, and forest professionals to improve the health of forests across the state.

I tracked down Professor Mark Ashton, the director of the School forest system, who gave me a brief overview of Myer’s ecological importance and history. We sat around a fire pit next to the crumbling foundation of a barn. He talked about the broader importance of New England’s forests: “Water filters down through the canopy, through the root system, and into the rivers and aquifers we get our drinking water from,” he told me, gesturing to the leaves and needles around us. “Urban planners in the Northeast realized that we had to protect our surface watershed by planting trees.”

Trees lit by the fiery colors of fall rimmed the shallow lakes alongside the road. Ahead of us, the tangled woods opened into a small clearing.

According to Ashton, the rich network of forests in New England, most of which was planted in the last hundred years, is one of the main reasons our drinking water is some of the best in the nation. “Without forests—in places like Louisiana, for example— instead of spending millions of dollars on a system that nature helps clean, you end up spending billions designing and engineering a system to get to the same water quality.” Nationally, the Environmental Protection Agency estimates that replacing our forest ecosystems with engineered filters would cost more than 270 billion dollars.

In the early 1800s, only thirty to forty percent of the region remained forested after waves of settlers made their mark. But as the country expanded, farmers abandoned their plots when they couldn’t compete with crops shipped by rail from the Midwest. Urban planners leapt at the chance to protect watersheds, purchasing vast tracts of land to ensure their preservation. Today, thick woods cover about seventy-five percent of New England—a surprising comeback driven in part by the economic forces often seen as anathema to conservation efforts.

After my visit, I spoke with Julius Pasay, the manager of the University forest system, in order to learn about what lies ahead for Myers Forest. Pasay makes executive decisions about the composition of the plots of land. He keeps Myers Forest as healthy as he can but he isn’t trying to return it to its “natural state” from before human contact. “What is a natural state?” Pasay said. “People have been interacting with the forests of New England for tens of thousands of years, and the distribution and migration patterns of species have been changing ever since the last ice age.”

Myers is a place where we look under the hood of forests, examining the forces that drive their dynamism and resilience.

The biggest changes in forest’s composition have been caused, unsurprisingly, by humans. Pasay told me about the chestnut blight started by a fungus from a Japanese-imported plant. It killed forty billion trees in the early 1900s. “These trees were everywhere, and you could just eat chestnuts right off of them.” He paused for a moment, thinking. “What would society be like if we still had those trees, if everyone had free access to food?”

Thoughts like this inform some of his most audacious plans for Myers Forest. Pasay has just finished planting an experimental “agroforest,” a network of different fruit and nut trees that has the potential to provide valuable habitats for threatened species and increase food yield. I asked him when he’ll know how successful he’s been, and he laughed. “Maybe in ten or twenty years? That’s the difference between agriculture and forestry—you work on a timescale of decades. I don’t mind, though. It feels like you’re paying it forward.”