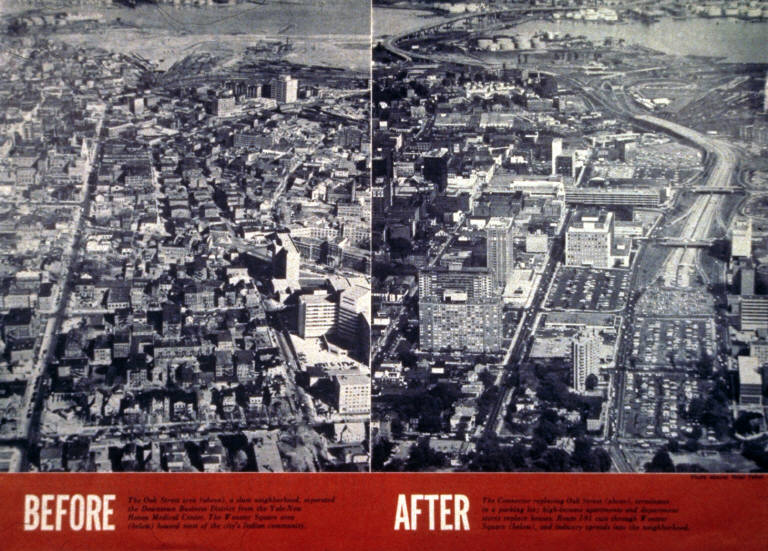

“What was Oak Street like?” former New Haven mayor Richard Lee asks his viewers in a short film made by his campaign in the nineteen-sixties. The film is black and white, stored in the Manuscripts and Archives department at Yale, and shows the changes made to Oak Street under Lee’s administration. “It’s almost impossible to describe how awful it was.”

In the film, Lee provides the voiceover as aerial footage of Oak Street, which divides the Hill neighborhood from downtown, before and after his administration’s urban renewal projects plays across the screen. In the footage from before renewal, a man sleeps on the street, trash is scattered around, and the camera peers inside dark, old-fashioned homes. Lee mourns the fact that there were people living subpar lives in a community that he believes should have been cleared out years ago.

In the “after” footage, the homes and buildings are gone, replaced by clean but desolate streets. Lee praises plans for new commercial buildings, new apartments and the headquarters of a telephone company. He describes the new highway, efficient and conducive to long-distance travel, in place of the area’s once-crowded streets.

When the old buildings finally fell, Lee says he thought of the early settlers, who tore down trees hundreds of years ago and cleared this land for “a better tomorrow.” In Lee’s view, mid-century urban renewal projects like this one were a continuation of the project begun in colonial times, where destruction was justified to make way for progress.

In 1959, the city, under Lee’s leadership, began construction of the Route 34 Expressway, colloquially referred to as the Oak Street Connector. This stretch of highway was intended to extend Route 34 from Interstate 95 through New Haven. Construction continued through the nineteen-seventies until federal funding dried up. Now, the Connector is stuck at a mile long, leading nowhere.

Oak Street is a part of the greater Hill neighborhood, and its demolition displaced 881 families, most of whom were working class, and 350 businesses. Renters could receive support from the city’s relocation services in finding new housing, but the requirement that it be affordable and of reasonable quality meant that some families were forced to move to neighborhoods far from their communities. Homeowners received the market value of their property, but property values plummeted when news broke of the urban renewal projects and people stopped investing in the area. Most businesses simply shut down, as they received little compensation and were no longer guaranteed the customer base that had made them successful.

Many families chose to find their new homes without the help of the city, so it’s difficult to know where they ended up. Francesca Ammon is a historian of urban renewal at the University of Pennsylvania, and during our interview, she said that most former Oak Street residents who could be tracked ended up in physically better housing, but were less happy. “They had trouble making friends and missed where they had been,” she said. “And that’s a typical story across the country.”

Another renewal project in Wooster Square displaced Theresa Argento’s first-generation Italian American family. Her family relocated to the Annex neighborhood in New Haven, but it never felt quite right, she explained during recorded testimony in the New Haven Oral History Project. “It was lovely. We had all the meadows. It was really beautiful and my mother was so unhappy. So unhappy. She thought we took her to California.”

The Connector’s construction destroyed communities and didn’t yield the economic benefits officials thought it would—in large part because it was never completed. It cut off the Hill neighborhood from the rest of downtown, and the neighborhood’s economy suffered both as a result of Oak Street’s demolition and the neighborhood’s effective isolation from the rest of the city. The Hill remains one of the poorest neighborhoods in New Haven, with a poverty rate above 40 percent.

Now, decades after residents’ lives were uprooted, the city is trying to rectify the harm inflicted by the Oak Street Connector. The Downtown Crossing Project began under former mayor John Destefano, Jr.’s administration in 2013, and its goal is to remove the truncated highway and transform it into walkable and bikeable boulevards.

But no amount of retroactive aid can undo the damage done to those displaced by the city’s decision to prioritize wealthy suburbanites commuting to the city for commerce over the inner-city, working-class residents of Oak Street. The community included many Italian and Jewish immigrants, as well as a number of Black families.

Samuel Slie, who died in 2019 at the age of 93 and was a pastor at the Church of Christ in Yale University, spoke about his childhood on Oak Street for the New Haven Oral History Project. In the tape, he discusses how his family lived on the second floor of a house with a tailor shop on the bottom floor, owned by a Jewish man with an Irish assistant. He described the schools, houses, stores, factories, and people. “I stress that to say we were all growing up together,” he said, “kids with all these different families.”

Sam Teitelman, who died in 2021, described the community in his own tape. “Everybody seemed to know everybody else,” he said. He and his family were Russian immigrants, and they were all quickly accepted into one of the many synagogue communities in the area. “You’d have meat markets, and grocery stores, and a shoe store, and a clothing store, and there was a very large grocery operation, fruits and vegetables and groceries.”

“Now, of course, it’s just that gulf of access space for modern transportation,” Samuel Slie said. Urban renewal, he said, became urban removal. The city became more segregated, public housing was torn down, and the people who fought against it were usually unsuccessful. “They took the heart of the middle class out of the city.”

Francesca Ammon dedicates a chapter of her book Bulldozer: Demolition and Clearance of the Postwar Landscape—the first scholarly account of the history of the bulldozer—to the history of urban renewal in New Haven. She writes that New Haven received more urban renewal grants per capita than any other city in the country, and in the nineteen-sixties, the city destroyed one out of every six dwelling units.

Richard Lee, the former mayor, spearheaded urban renewal in New Haven. He embraced the opportunity to be at the forefront of progress, and happily took part in photoshoots in which he would sit in the operator’s cab of a wrecking crane, surrounded by demolition.

This process of urban renewal, even outside of New Haven, implies an inherent contradiction. Progress and renewal require demolition. When the city builds a highway, it razes neighborhoods to the ground. Prosperity in the form of modernization is made possible by rubble and bulldozers, or a wrecking ball tearing through the wall of an old tenement building. In the Oak Street community, those homes were filled with working class Jewish, Italian, and Black families, who suddenly had to find a new place to live—a place that never quite felt like home. It’s difficult to believe what happened here to be progressive when an entire community was erased.

John DeStefano, Jr., who was mayor of New Haven from 1994 until 2016, mentioned in our interview that Richard Lee had been a friend of his. I asked how Lee later felt about the decisions he made regarding urban renewal in New Haven, after seeing its effects. DeStefano paraphrased something he’d heard Lee say much later in his life: “‘Our ambitions were glorious, and our failures were spectacular.’” DeStefano thinks Lee had good intentions, even though DeStefano’s own grandmother’s house was demolished in the process.

“There was this moment in America,” he said, “where cities and rebuilding cities were central to the national political dialogue, which it is not now.”

In 2013, phase one of the Downtown Crossing Project (DCP) began. The project originated during DeStefano’s mayoral administration in the early two-thousands. By this point, urban renewal was widely seen by both residents and city officials as a mistake.

“[The Connector] created this linear wall that people didn’t walk across,” DeStefano told me, when I asked why he found the DCP necessary. The construction of the Connector created what is effectively a dead end, he said, where people don’t feel comfortable walking. “Commerce didn’t thrive.”

Through phase one and phase two of the Downtown Crossing Project, the city has been able to make more taxable property available for development while slowly beginning the process of highway removal. Soon, Orange Street and South Orange Street will be connected by a pedestrian and low-speed vehicle friendly intersection. Once the federal government agrees to fund phases three and four, Temple Street and Congress Avenue will be fully connected.

“It is the goal to provide economic development opportunities for people that live in the surrounding neighborhoods, including the Hill,” Donna Hall, the senior project manager of the Downtown Crossing Project, told me. The idea is that the new accessibility of the area will allow residents to be more mobile and connected to the rest of the city. It hasn’t been easy. “It took years of negotiation and study with the Federal Highway Administration,” she said, to ensure the city could build the intersection and still accommodate traffic.

The website for the project reserves space to discuss the Oak Street community and the city’s role in its demolition. Under the “history” tab, there is a description of the diverse families who lived on Oak Street, and an acknowledgement that the city prioritized automobility over community cohesion. The maker of the website has included a photo that emphasizes Oak Street’s “before” and “after”—but the destruction isn’t a source of pride like it is in Richard Lee’s short film.

The Downtown Crossing Project is an attempt to rectify some of the harm inflicted by urban renewal. But for the hundreds of families expelled from Oak Street, and for the countless other working-class residents of New Haven whose lives and livelihoods were upended by urban renewal, it’s an attempt that comes sixty years too late.

Dereen Shirnekhi is a junior in Davenport College and an Associate Editor of The New Journal.