Where was it that I first heard the rumors? Was it a comment on a drive back from a bike race? A stray remark at a holiday party? I struggled to believe that one person could be so many things: a Yale professor, the architect of Obamacare, and the fastest cyclist in New Haven. Looking to separate truth from fiction, I set out to find the man.

I had started biking more seriously only during the pandemic. Hours of open road and blue skies served as a vital escape from the constraints of lockdown life. But the risks of the sport always weighed heavily upon me. Riding on the shoulders of car-filled roads, I thought often about what would happen if one of the cars swerved. Perhaps a ride with an expert in healthcare policy could help me figure out if the sport was really worth it.

On the same day that Obama visited the White House to mark the 12th anniversary of the passage of the Affordable Care Act, I met Jacob Hacker, Stanley B. Resor Professor of Political Science, outside his East Rock home. I could spot his neon-yellow gloves from two blocks away, the only spot of color on his otherwise all-black, skin-tight kit.

In his professional life, Hacker is most known for his work on social and public policy. Though he didn’t create Obamacare, he did generate the idea for the public option, a government-created health insurance plan that would have functioned as an affordable alternative to options on the private market, though it never became law. Elsewhere in his work, he has written about how the U.S. government has transferred burdens and risks from corporations onto individuals and the working class in the post-Reagan years of anti-government politics. You might not guess it while watching Hacker cycle—in the groups he rides with, bikes are worth sums that others would not save in months—but concern for lower-income citizens permeates his writings. One of his books—Winner-Take-All-Politics: How Washington Made the Rich Richer and Turned Its Back on the Middle Class—became a New York Times best-seller during the Occupy Wall Street protests.

After meeting at his house, we set off for Sleeping Giant State Park, a dozen or so miles from Yale’s campus, and the site of a weekly road ride that is notoriously brutal and fast. Hacker insisted he’s not the fastest cyclist in the city today, but he is one of the fastest. I had no hopes of keeping up with Hacker and his fellow racers once that ride began. So, as we rode up through East Rock and then north out of New Haven on our way to meet the group, I worked to get in as many questions as I could. More theoretical questions about, say, the neoliberal resonances of cycling tights, would have to be explored another time.

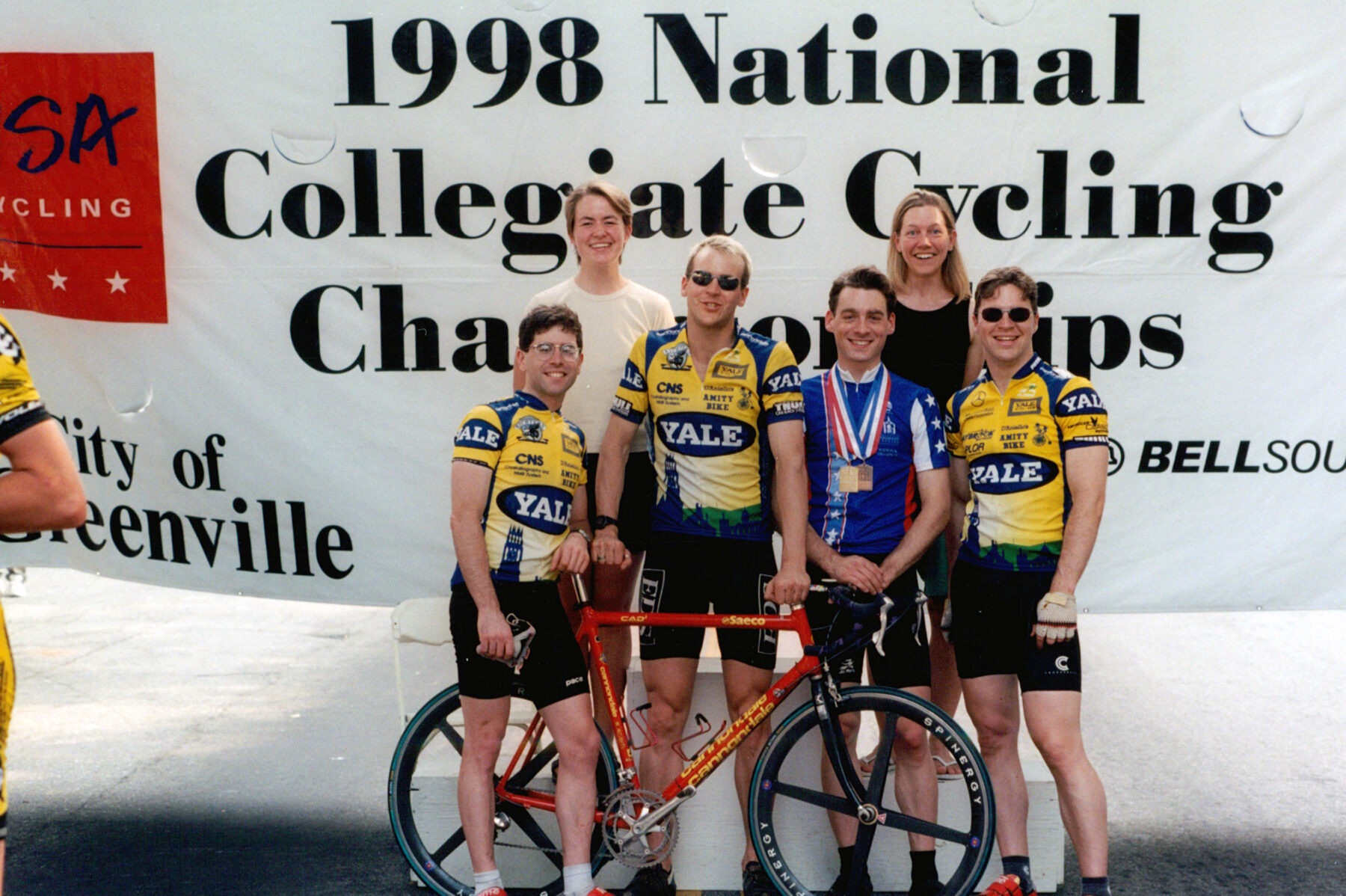

As our ride progressed, it became clear to me that Hacker is the closest thing to Rob Lowe’s The West Wing character I could hope to meet in person. A three-time collegiate national cycling champion, he’s a triple threat: a celebrated intellectual, a top-tier athlete, and, frankly, pretty handsome. On the day of our ride, even Hacker’s salt-and-pepper stubble seemed to sparkle.

As Hacker and I dodged protruding sewer grates and made way for passing cars, I asked him about some of the darker aspects of the sport he has come to love.

I jumped straight in.

“Have you had any friends get killed while cycling?”

At the heart of road biking, there’s a bit of a paradox. If all goes well, you usually come back from your ride energized, relaxed, and more tolerant of the irritations of daily life. Exercise is understood to improve mental health, and if it’s true of running on a treadmill, it’s a good bet for biking as well. Whizzing through the countryside with little beneath you but a pair of wheels and nothing above you but the sky, life is better.

The risks of the sport, however, are hard to ignore. More than eight hundred cyclists have been killed each year since 2015, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. And though the odds of getting hit on any given ride might not be particularly high, it’s little consolation as an eighteen-wheeler zooms past. Cars have passed me by little more than the length of the hair on my legs.

Hacker told me he hasn’t had any friends killed in bike accidents, but he’s had some bad crashes of his own. A number of years ago, he was riding with a group from New Haven down Connecticut Route 17 when he struck debris in the road. Unable to react in time, he was catapulted headfirst into the road’s side rail, and his face split open. The other riders in the group called 911 immediately, and he was rushed to a hospital where he received the care he needed. If they hadn’t been present, things may not have worked out as well.

“I would probably be dead,” Hacker said.

After the crash, he did not cycle for a long time, and he questioned whether the sport was really worth the risks. I asked him what ultimately brought him back. “The joy,” he replied.

The shoulder narrowed, and he pulled ahead of me as we rode over a highway overpass. In the distance, the clustered trees of a nearby state park sat unmoving beneath the overcast, light gray afternoon sky. To our right, a pair of birds circled patiently in the air. Moments later, a pair of cars took the opportunity to pass us. The noise of their engines growled in our ears from a few feet away, and my left-side peripheral vision was momentarily subsumed by a rush of black and gray, the colors of the cars driving past. A blend of suburban tedium, car-induced micro-terror, and pastoral ideal, it’s typical of rides in the area.

We turned off Ridge Road and wound our way through a hilly neighborhood that sits between Hamden and North Haven. Feeling short of breath, I bracketed hopes for extended conversation and focused on keeping up. Hacker, ahead of me by a few bike lengths, had crested the section’s final climb and began the descent. As I pushed my way to the top, Hacker tucked his forehead to his handlebars to minimize air resistance and sped down the hill. A driveway sat treacherously at the bottom of the hill, partially hidden by a curve in the road. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, the thinking goes, a driver would look both ways before exiting the driveway. As for the one in a hundred? Hacker and I are lucky to have health insurance.

—Yonatan Greenberg is a senior in Saybrook College and an Associate Editor of The New Journal.