Reporting for this piece was made possible by the Ed Bennett III Memorial Fund. Design by Kevin Chen, adapted for web.

Editors’ Note: Some identifying information and comments have been revised from the print version, in keeping with The New Journal‘s new policies regarding anonymization of sources.

Kelsey M. had just turned eighteen when she was approached on the way back to her dorm in Seattle by someone asking if she’d heard about “God the Mother.” Curious, she agreed to attend a Bible study the next day, at the end of which she was baptized.

When she was first approached, Kelsey was new to the area, having just moved for college. She had no family or friends in Seattle. The people who had invited her to attend a Bible study looked around her age and seemed friendly, so she decided to tag along.

In a matter of weeks, she was in so deep that she was prepared to “literally die for the Church.”

Kelsey was recruited during what the Church calls a “short-term mission”, in which members from Los Angeles are sent to cities like Seattle to preach for about a week and baptize as many people as possible. “Everything they said to me made logical sense, for example, because they believe in a God the Father and God the Mother, they said just as every living creature on this Earth requires a father and a mother to be given life, in the same way, we have to have a God the Father and the Mother to be given spiritual life,” Kelsey said. “They use a lot of real life examples to justify or explain their doctrine, to make it more digestible.”

During such missions, Kelsey told us, the recruitment process is “sped up,” which means important, secret tenants of the Church are divulged earlier than usual. Perhaps their most important belief is that their founder, a twentieth century minister named Ahn Sahng-hong, is the second coming of Christ. Many other members that we spoke to only learned about Ahn Sahng-hong after several months in the Church. What Kelsey did not learn right away, though, was that Ahn’s spiritual wife—a living South Korean woman named Zahng Gil-Jah—is God the Mother. She was told this explicitly only after three years in the Church, by which time she was in so deep that she didn’t think to question it.

The church that Kelsey joined is known as the World Mission Society Church of God, a religious Bible-based movement that was founded by Ahn Sahng-hong in South Korea in 1964. Kelsey told us that the Church teaches preaching members to only reveal its beliefs and practices bit by bit, because the more radical beliefs of the Church—such as the fact that God the Mother is very much alive—would “scare [newly recruited members] and they’re not going to want to listen to the truth.” The Church allegedly justifies this through a verse in 1 Corinthians that says, “I fed you with milk, not solid food; for you were not yet able to receive it.”

Last spring, a division of the Church known as ASEZ, or Save the Earth from A to Z, sought to establish a student organization at Yale. We investigated ASEZ for the Yale Daily News in April of 2022 and spoke to ten students who attested to having been approached by members of the Church on campus, as well as a few who’d actually joined. One student, Charnice, who joined for a few months, was told to miss class and other extracurriculars to focus on her “spiritual family.” Another student, Davornne Lindo ’22, became a Freshman Counselor (FroCo) while actively involved in the Church. At the time that we interviewed ASEZ, the group was spearheaded on campus by Davornne, who has since graduated, but from student reaction to the article, we learned that there was a wave of attempted recruitment from as early as 2018. The Church’s closest location is in Middletown, Connecticut, but over the last year, they have mainly invited students to Bible studies at the Starbucks on Chapel Street.

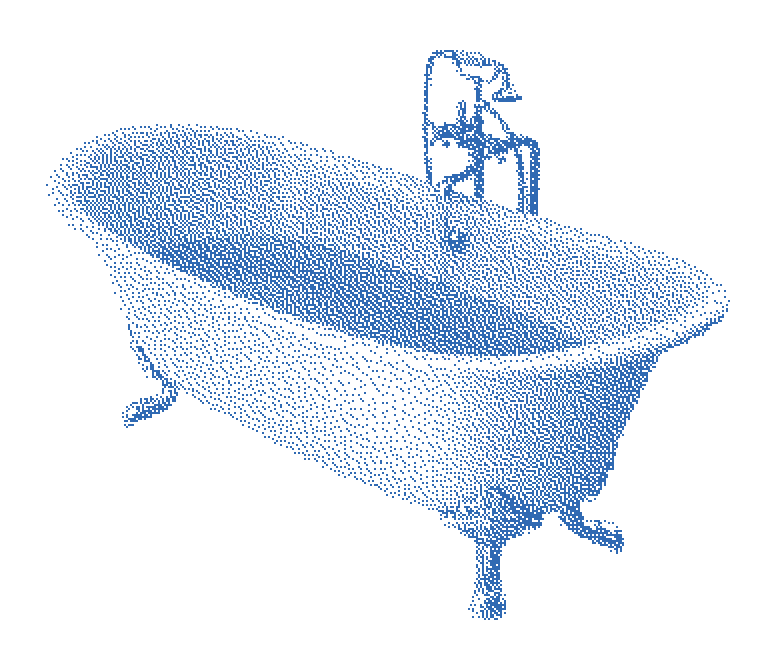

Yale students might recognize the group’s recruitment tactics from personal experience. Usually in pairs, members of ASEZ would approach students in coffee shops or on the street between classes, asking if they’d want to join for Bible study. If the answer is no, a student might be subjected to a few minutes of earnest persuasion before they’re left alone. If the answer is “sure”, they’ll likely be invited to a Bible study at the Starbucks on Chapel Street or a room in Bass Library. Students on other university campuses have described being loaded into a car and driven to a church building, where they’ll sit down with other members for hours of worship, at the end of which, usually, awaits an impromptu, Do-It-Yourself baptism in the church bathtub.

We were able to meet Kelsey, and many of the other sources in this article, through a small online community of ex-members-turned-vocal critics of the World Mission Society Church of God. Kelsey told us that the Church’s “target audience” is young adults aged between 18 and 30 years old. “Basically, anybody who is not tied down with a family and can just dedicate their entire free time to the advancement of recruitment for the group,” Kelsey said. “That was number one. That’s why you see them on a lot of college campuses.”

But the question of the legitimacy of the Church, which has been accused by former members of being a “cult,” and the intense, often unsettling commitments it asks of its members, goes much deeper.

Students on other university campuses have described being loaded into a car and driven to a church building, where they’ll sit down with other members for hours of worship, at the end of which, usually, awaits an impromptu, Do-It-Yourself baptism in the church bathtub.

The Bible studies and church services that Kelsey attended were initially not held at a church, but at a member’s house. Every Saturday, she and other members would gather there from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. for three hour-long services, meaning that she was “constantly surrounded” by the same people. “When you start college, you’re very impressionable, everybody’s kind of trying to figure out the world around them at that time,” Kelsey said. “Everybody in the Seattle church at the time, we all just sat around one dinner table, so it was a bunch of people who had no family, no friends in the area…and we literally just became like a family.”

Things moved quickly for Kelsey. Her fellow members were all the friends she had in Seattle, and because she hadn’t previously read the Bible, she was quick to believe what they told her. For Kelsey, a lot of her first experiences in the Church weren’t immediate red flags—even if she was spending copious amounts of time at the church, it initially didn’t strike her as concerning. In fact, like all of the former members we spoke to, Kelsey described the tension between the Church as a toxic and controlling institution, and her fellow members being kind, friendly, and drawn to the Church for many of the same reasons as herself. This is what made it so hard for her, and others, to leave.

In July, we visited the New York City branch of the Church for their 3 p.m. service. We found the address on the internet, and at the front of the two-story office building was a sign that read “Ring the doorbell if the door is locked.” The door was not locked, so we entered through the glass doors into a makeshift waiting room with just an elevator. Certificates of philanthropic awards hung on the walls around the room. We stepped into the elevator to go up to the second floor, where the services were being held. But the elevator did not budge and the doors stayed open. After a couple of minutes, we stepped out and rang the doorbell—which had a Ring camera—outside the front door. Just then, the doors of the elevator closed.

As we debated calling the elevator again, the doors opened to reveal a tall man dressed in a gray suit. He began to question us: how did we know about the Church? Why were we there? Who’d invited us? Services were invite-only, we were told, for the protection of the members. It did not matter that we had called a week earlier and been told that services were open to all by someone who subsequently stopped answering our calls.

He instructed us to come back in half an hour for activities, when the service was over. So, we did. For the next thirty minutes, we sat kicking our legs on barstools at a restaurant next door, sweating in the New York City heat, debating our next move and guessing at what exactly “activities” might mean. But when we were let up to the second floor, there were now two men standing in front of the elevator door, barring our way. The second man, we found out, was Victor Lozado, the overseer of the New York and New Jersey branch. Members were being sent home early because of the heat wave, they said, so now was not a good time. It would be best if we could put our names down so they could contact us for a future Bible study. Members, all dressed in suits and blazers, despite the heat, streamed outside in twos and threes—but a few minutes later, they reentered the building through a door to the side of the main lobby. There was no indication that any of them were going home for the day.

The origins of the World Mission Society Church of God are more complicated than the Church makes them out to be. Searching for information about Ahn online leads to a deluge of mixed information. The blog Examining the WMSCOG is run by a former member who is dedicated to unveiling the doctrines of the Church, and there are at least a dozen counter-blogs that attempt to hide and invalidate any criticisms of the Church. Googling “How can Ahn Sahng-hong be the Christ” brings up pages of those counter-blogs, like The True WMSCOG and The True God the Mother, in addition to the Church’s regional websites. But there is little information about the man himself.

From what we were able to find, Ahn Sahng-hong, a 46-year-old South Korean Christian minister, founded the Church in 1964 under the name Church of God Jesus Witnesses in Busan, South Korea. Born in the Jeollabuk-do province of South Korea in 1918, Ahn grew up in a Buddhist household. In 1946, he converted to the Seventh-day Adventist Church. According to the website for the World Mission Society Church of God in Korea, he began receiving revelations from God in 1953, and in 1956, Ahn predicted that there would be the second coming of Christ within the next decade. In 1962, he was excommunicated from the Seventh-day Adventists.

Ahn taught a literal interpretation of the Bible, something he felt the Christian Church had distorted. He believed that Christian iconography like symbols of the cross was a form of idolatry; that the Sabbath should be observed on Saturday, not Sunday; that women should wear head coverings while praying; and that humanity is living in the end times, when the end of the world is imminent. In his books, The Mystery of God and the Spring of the Water of Life and The Bridegroom Was a Long Time in Coming, and They All Became Drowsy and Fell Asleep, he predicted that the world would end forty years after the creation of the modern state of Israel in 1988.

After Ahn’s passing in 1985, the original church split into two separate sects: the New Covenant Passover Church of God, led in Busan by Ahn’s son, and the Church of God Witnesses of Ahn Sahng-hong. The latter, which was rebranded as the World Mission Society Church of God in 1997, was led by Zahng Gil-Jah and the general pastor Kim Joo-cheol. While the New Covenant Passover Church of God believes that Ahn was just a prophet of God, the World Mission Society believes he is God himself—and they believe that Zahng is Ahn’s “spiritual wife”, and God the Mother.

The Church’s presence on campus isn’t new. After our first article in May, we learned that students have been approached on campus since as early as 2018.

Zahng is an ever-smiling 79-year-old woman living in South Korea. According to a letter allegedly written by her first husband Kim Jae-hoon, Zahng and Kim were married in 1966 and began going to Ahn’s church together. They had two children, but as Zahng became more and more involved with the Church, she sold their house to pour money into the Church and began to neglect her family. Eventually, they separated in 1987.

George, whose name has been changed to protect the identities of his family members, was born into the Church and remained a member for twenty-one years. His parents married when his father served in the United States military in South Korea, and both of his parents initially joined the Church. While his mother was “indoctrinated fast” and “very devout,” George said she still was not as “into it” as his father. His parents separated, and George has not seen his father in ten years. Based on his Linkedin, George believes his dad is now a missionary for the Church and works for the Red Cross.

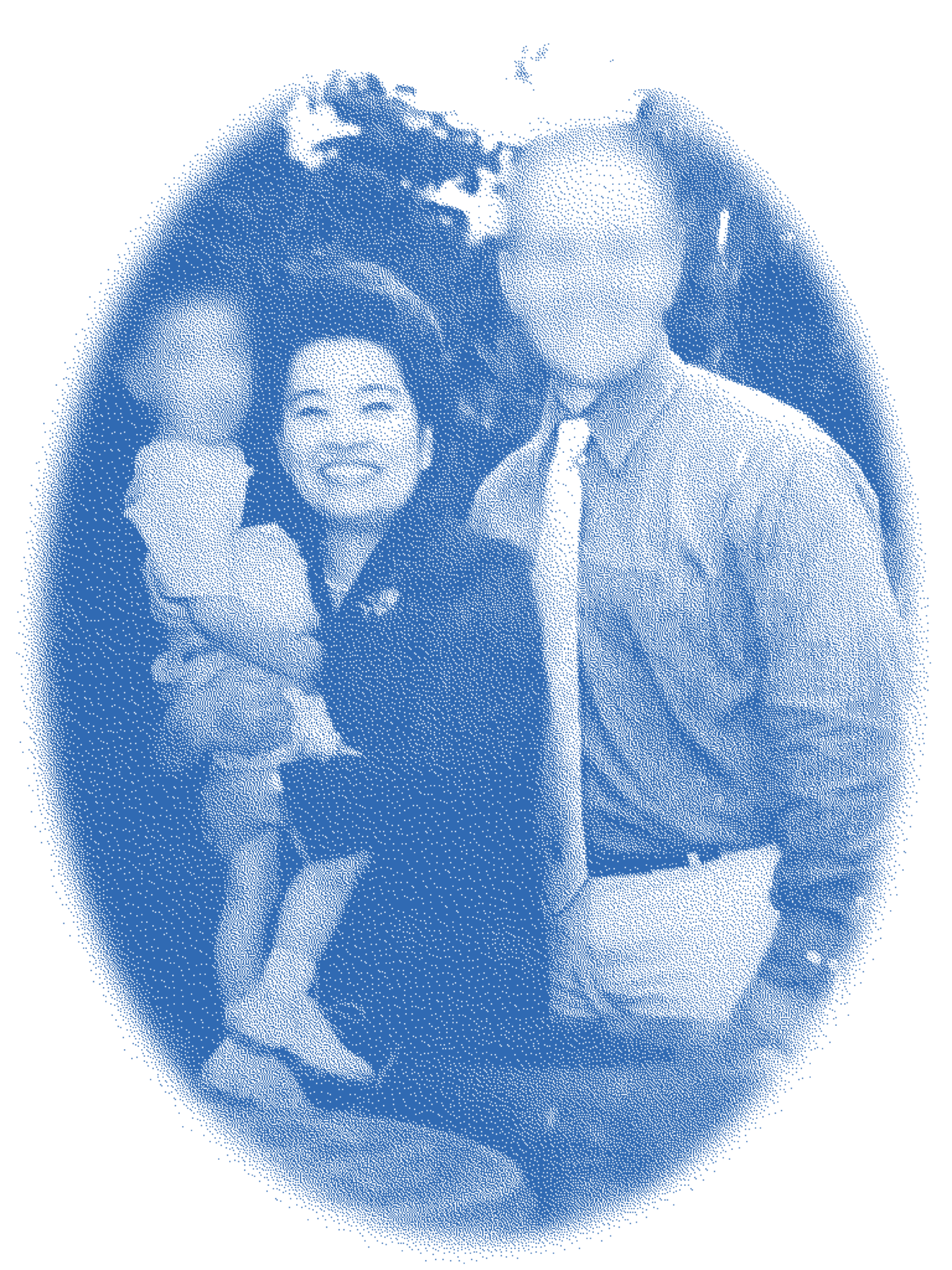

George met Zahng at the main temple in South Korea, once with his father as a young child and later again with his mother as a teenager. Each time he met her, he believed fully that she was God. She was charismatic and maternal. After a service, she would sit alongside a translator as a line of people came up to meet her. Often, George said, people would describe what they were struggling with in their lives.

The World Mission Society Church of God has been awarded with multiple philanthropic awards, as has Zahng herself. Her website, and the website of the WeLoveU Foundation she founded, describes her philanthropic ventures as evidence of “the Love of a Mother.” Members of the Church frequently participate in community service—receiving media coverage almost every time—and the Church ostensibly founded ASEZ as a means for university students to get involved with the service-side of the Church, without having to participate in the Church’s religion.

According to Anthony Forte—another former member who joined the Church in 2011 and left in 2021—however, members of the Church are aware that ASEZ is what he called a “front group,” created just to recruit more members into the Church. He pointed out the contradiction between the Church believing the world is going to end any day now, and ASEZ carrying out environmental efforts that should, under this religious belief, have no real effect on whether or not the world is saved. When members pointed this out to church leaders, Anthony said, they were reassured that “Save the Earth” meant to recruit the people of the Earth to their church to be saved, not the planet. ASEZ also gave the Church opportunities to legitimize itself, Anthony said, through photo opportunities and the collection of awards from governments and official organizations for their hours conducting service. But Victor told us that this was ridiculous. He emphasized that ASEZ was created by university students in the Church who were only interested in furthering the Church’s service mission; they “wanted to bring what they learned in the Church, into their school,” he said.

“We cannot help people feeling like ‘Oh, but I have to join the Church’ [and that feeling] will keep them from helping even though they could,” Victor said. “So ASEZ was essentially that we want to bring the actual preaching to practice rather than directly preaching with the Bible.”

An email we obtained sent by Brittley Timmons, the administrator of the Church in Maryland, included a spreadsheet that described ASEZ activities as a method of building relationships, which is a key step in church recruitment.

Victor recognized us from our first article in the News. After we were asked to leave the Bronx church, he stepped outside and, seeing us, rattled off a list of reasons why the Church had to be wary of the media. A balanced perspective was all he was asking for, and that was something he said he would be willing to provide. He agreed to meet for an interview, initially suggesting a Starbucks in Manhattan, on the condition that we attend a Bible study first—something that he said all reporters were asked to do.

After a month of back and forth, Victor offered to drive up to meet us at the Middletown church. Sitting at the back of a white and beige meeting room with several rows of seats, the pastor of the Church, a tall, ever-smiling Korean man who later called himself the “selfie king,” brought out a tray of snacks. He set up a screen at the front of the room and began screening half an hour of videos about the Church including dozens of videos of church members across the world gathered in large groups, smiling, waving, and exclaiming “We love you!” As we were leaving, after asking us to take a selfie with him, the “selfie king” gave us goodie bags filled with baked goods, a mug inscribed with a Bible verse, and a note that ended with another “We love you.” Victor’s story is familiar. He first joined the Church as a 20-year-old college student in 2005 in Bogota, New Jersey. He was invited to a Bible study after soccer practice. He said he’d tried out several churches prior to joining the World Mission Society, but found that many churches did not “practice what they preached,” including the Catholic church in which he grew up. Once he saw the “evidence” from the Bible about the Sabbath, he knew the Church of God was “different”. (The evidence: Mark 16:1 states “Saturday evening, when the Sabbath ended.”)

Victor was baptized a few days after his first Bible study.

Ava, whose name has been changed to protect her identity, is a former member who was in the Church for about two months. She, like Kelsey, was baptized at her first Bible study, but she had not been told almost anything about the Church’s beliefs. According to Kelsey, once you are baptized by the Church, you’re considered a member.

When the World Mission Society first approached her, Ava had just graduated college. Two women around her age approached her in the Christian aisle of a bookstore. At the time, she had been interested in learning more about Christianity, so when the women asked her to join them for a Bible study, she agreed to go the next day, despite the women urging her to follow them into a car immediately.

When she went to the Church, Ava noticed photos of Zahng on the walls and accepted their explanation that that was God the Mother. Looking back, she chalks this up to naivety. At the end of the Bible study, she was taken to a separate room of the house with a tub, where she was submerged underwater. “It seemed like a normal Bible study, nothing out of the ordinary,” she said. “I liked what I heard, so they asked me if I wanted to get baptized, and that’s something I actually regret.”

The feeling of regret kept coming up throughout our conversation with Ava. She had joined the Church and allowed herself to be baptized because she was genuinely interested in Christianity. Later, she learned that the Christian leaders condemn World Mission Society as a cult, and this made her wonder if she had tainted herself. “I regretted [the baptism] very much. I felt like what have I done? How did I ruin my chances to get to heaven?” Baptizing members before they’re devoted is a way to make them feel committed to the Church quickly. At the time, though, she believed the group when they told her she had to be baptized in order to see salvation, so that Saturday she returned to the house for World Mission Society’s day of sabbath where they worshiped and studied the Bible nonstop—it felt like “cramming for an exam.” Everyone was cooped up in the house from morning until night, breaking only for meals.

“We spent the entire day at that house and it was exhausting,” Ava said in an almost confessionary tone. She felt almost guilty that she had allowed herself to be baptized, and kept apologizing for how “ignorant” she had been about religion at the time. “I’m going to be honest with you, it’s an experience I’ve never experienced before. At the end of that day, it felt like a physical change happening, like [my brain] was being reworked and reformed.”

Over time, however, questions began to pop up. She had contributed to gifts and monetary donations for “the heavenly mother” in South Korea, and the Church had played a “thank you” message from God the Mother at the next service. Ava wondered why, if the woman in South Korea was God, she only responded by nodding and smiling, and could not respond in English. She’d also seen mentions of Ahn Sahng-hong as the second coming of Christ on the internet—something the Church hadn’t mentioned to her at all—which she brought up at one of the Bible studies. To each of her questions, Ava said she was only told by the members conducting the Bible study that she was “ignorant,” “dumb,” and should not have “read ahead.”

She eventually left and joined a Methodist church. She told us that she wants to get re-baptized to “wash away” what happened. She felt “betrayed” by the two women from the bookstore, whom she had considered her friends.

Kelsey, too, described her baptism as an uncomfortable experience.

“They didn’t tie my hands and throw me into a bathtub,” Kelsey said. “But the thing is, I don’t believe that I had the information necessary to really make the choice on my own, because they were not forthcoming with all the stuff that was going to be required of me.” Both Kelsey and Ava told us that the intimate space where their baptisms took place and the group of people that surrounded them made them feel pressured to agree to the baptism. “They tell you in order to be saved and enter the kingdom of heaven, you have to be baptized and they show a verse in the Bible that says you don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow,” Kelsey added. “So there’s some element of fear tactics as well.”

Anthony recalled being similarly baptized at his first Bible study. He felt like he had been misled. He was not religious at all before joining the Church, did not have any experience and had little knowledge of baptism, and was told that he would just “get a little wet.” Instead, he was led to a room where he was asked to take off all his clothes and change into a robe. He kneeled down while a group of about five people prayed over him—it felt like a “whirlwind.”

“In my mind, it was a ceremony where maybe they sprinkle water and then that’s really the end of it,” Anthony said. “But they ended up making me walk up to a room, where they told me I had to take off all my clothes and put on a robe and I felt like that was deceptive…But I already felt this peer pressure, these people are all excited and surrounding me excited that I’m going to be baptized…what am I supposed to do?”

Victor told us that the immediacy of baptism within the Church is based on their commitment to following the Bible. “In the Bible, every baptism was immediate. There is no record of a baptism being delayed by six months or a year, so it is taught in the Bible that if someone wants to be baptized, they can do it the same day.”

They stressed that members should be ready for the world to end at any moment, and they should prepare by devoting themselves completely to the Church.

At the end of November, a month after we’d sat down with Victor, we wrote him with a list of the allegations former members had brought forward — allegations that had “legal implications” according to his reply. The next day, we received an email with fifty member testimonies attached as letters mostly addressed to “whom it may concern”. These letters, featuring the writers’ first and last names, detailed their positive experiences with the Church. In Victor’s words, “with over 4,000,000 members worldwide everyone has different experiences, and to write a story about our Church only from the perspective of “former members,” its unfair to all the members who currently attend the Church, and whose lives have improved since having joined the Church.”

A member of the Church for seventeen years, Zuley Polanco, described how her husband, whom she had met while at college, eventually began attending the Church with her. “We got married and for a long time I attended the Church of God alone which was never a problem but I still wanted him to be a part of this beautiful organization,” she wrote. “So, I invited him to one of the many events held at the church and he was very impressed by how much the Church of God does for the community and the countries around the world.”

Another member, Youngbae Song, who has attended the Church since 2007, wrote that the Church helped him to understand the “importance” of keeping God’s commands: “I realized that no other churches I attended were actually following the teachings of God in the bible, but practice many pagan customs.”

Youngbae described how the Catholic mother of one member called her daughter and decided to visit the Church because her Catholic priest had said to their parish: “if you want to believe in God, you should be like the members of the Church of God.”

“It is a miracle!” Youngbae wrote. “Many co workers and family members came to Church of God because they realized how much the members who attended had changed for the better after attending the church.”

Many of the other testimonies read with the same zeal, describing how the Church changed members for the better, and that their spiritual change compelled friends and family to attend too. Many of them describe their former selves, before joining the Church, as selfish or lost; after joining the Church, Ivan Diaz wrote that he began helping out around the house and became a more positive person. Several mention finding the “truth”—sometimes with a capital “T”—through the Church. Although the accounts represent the variety of experiences within the Church—many of which, according to Victor, dispute the claims of former members — there are some elements that connect the testimonies to each other and to those of former members. The recruitment that Kelsey, Anthony, and George describe being tasked with is reminiscent of Pablo Chavez, who “could not help but to invite” his family, friends, coworkers, and classmates to the Church and Naomi Timmons who realized that “everyone must know about and come to this church!” Time spent at the Church that would stretch past midnight each day is described by Saira Ahmed as the Church becoming her “home”—“Day after day, no one needed to call me to ask if I was coming,” she wrote. Many described being disillusioned with other religions before finding the Church. Several of the members described having a family while in the Church, children who would attend Bible studies and Sabbath days and eventually begin preaching to others. Several of them described having spouses who weren’t originally in the Church—but all of them either ended up joining or separating, although one describes another member who is not a member of the Church. A few of them did describe learning about God the Mother early on. Several of the testimonies, like Jaewon Kim’s and Jenn Garcia’s, also describe joining the Church while at university, although they emphasize that the Church did not interfere with their studies or extracurriculars.

One member, Ashley, graduated from Yale in May 2018 and worked at Yale from 2018 to 2020. While she was at Yale, she was not particularly interested in the Church, being more focused on her academic and professional goals. She recalled being introduced to the Church through two girls who approached her and her roommate at a mall: had she heard that the second coming of Christ had already come, they asked her. Not understanding the name “Ahn Sahng-hong,” she asked them to repeat it four times before feeling “relieved” to learn that the reason she couldn’t understand it was because it was Korean. After a few Bible studies, Ashley was baptized—a rite in order for her to “keep the Passover and receive the promise of God.” The Church taught her that many of the things she thought she knew were not biblical: “I felt so hurt by all those churches that taught me those things that had nothing to do with what God commanded us. I felt lied to and I wanted to know the truth.”

The Church calls new recruits, people who attend at least one Bible study, “fruits.”

“Bearing fruit,” Kelsey said, meant bringing somebody to the Church who then gets baptized, and each fruit that a member “bears” earns them points at the main Church in South Korea. If a fruit begins contributing monetarily—through tithes and offerings—they are then called a “talent.”

Tom, whose name has been changed for privacy reasons, became involved almost seven years ago as a senior in high school when he was messaged by a coworker he liked, asking if he would come to the Church of God. He didn’t think much of it, and saw it as an opportunity to get to know this girl and thought it could be interesting. He said he found the people the Church uses for recruiting are either young college students or attractive women.

About a week after she messaged him, he went to the Church, then only stayed in the Church for a few months, but he could already tell that something wasn’t right.

Tom said the Bible studies seemed normal at first, although he did not have much religious experience, but he said things started becoming “weird” and “strange,” especially with the long church services and how he found members of the Church were “out of touch with reality” and “brainwash[ed].”

They also encouraged him to not talk to people who did not agree with the Church’s ideas, which he also found strange, and said they would “do anything they [could]” to get him to stay late at the services, leading him to often lie and tell leaders he was sick to get out of commitments for the Church.

“They don’t strike me as somebody that would, you know, hurt you physically, but they will do anything necessary to mentally convince you to stay,” Tom said.

In 2010, Kelsey said that the Church taught that the world would end in 2012 and that each member had to bring in ten talents in order to ensure their place in heaven. The Church called this the “ten talents movement.”

“It was so incredibly stressful, and meanwhile 2012 passes and they said, ‘Mother’s giving us more time to bear the ten talents,’” Kelsey said. “2012 comes and goes and we’re still here, and the Church backtracks and says, ‘We never taught that the end of the world was going to happen.’” (Members had been taught to physically prepare for the end of the world by buying an army duffle bag, a month’s worth of food, and a month’s worth of water.) But the Church was still expecting its members to recruit.

The Church, allegedly, would simply move the date of destruction further back. 2014, the fiftieth anniversary of the Church, was the next date, and when that passed, they said the world would end in 2018. They stressed that members should be ready for the world to end at any moment, and they should prepare by devoting themselves completely to the Church.

“If Father comes tonight, you want to be found doing the gospel work,” Kelsey said. “They had it in your mind that Ahn Sahng-hong could come back at any moment and destroy the whole world, and they would tell us that you need to be prepared to watch your children die in front of you and still be faithful.” Kelsey felt that to be prepared she had to be constantly preaching, studying the Bible, or doing work for the Church.

Kelsey and other former members recounted frequent offerings that were required by members, including a tithe of 10 percent of your annual pre-tax income. Victor emphasized the importance of a tithe as a biblical teaching, but said there is “free will” with every teaching of God, explaining that the tithe is not enforced. After all, he said, God wants a “cheerful giver.”

A 10 percent tithe is described in the Bible in Deuteronomy and is also required by some churches including the Seventh-day Adventists and the Church of Latter-day Saints, but is voluntary for the most part in other churches in the United States.

Kelsey, however, told a different story.

“They say they don’t require anybody to tithe, and that’s a lie,” Kelsey said. “When I first joined, all I was required [to give] was tithes and offerings…but the more I got involved in the Church, the more that they started asking me for.”

Eventually, half of Kelsey’s salary was going to the Church. She was purchasing lights for the building, cooking for the whole congregation twice a month, and, when she became a leader in the Portland branch, she was spending an additional $250 to $300 a month to provide meals on sabbath days for up to 120 regular members. If there were seminars, construction at the Church, or materials needed for the children’s classes, Kelsey also had to front the cost. “It got to the point where by the time I left the Church, roughly 40 to 50 percent of my paycheck was going to the Church every month,” she said.

When asked about members like Kelsey having to spend large sums of money, Victor said, “I don’t know what that means.”

Anthony also recalled having to give large sums of money. He said every time you receive a paycheck, you were told to tithe 10 percent of your pre-tax income and “always round up” if there was change involved. There would be an offering on Saturday at each of the three services, and once a month, there would be a “brown envelope” which goes to international churches or towards planning for church missions and included a “thank offering” that members contribute to once a month. In addition to these donations to the Church, they also have “the feasts of God” which are special celebrations involving at least seventeen different ceremonies throughout the year, each of which requires extra donations in two offerings per service, on top of food donations or donations towards specific events.

“I’m sure that some of it goes towards the upkeep of the building, but even when they do construction work, a lot of the time the members are just contributing more and more,” Anthony said. “So it seems limitless, how much they ask the members to give, and you don’t really see where it goes. It seems like they just take tithes and offerings and they completely put it aside, and then the members continue to feed into upkeeping the building and the food and everything like that to keep it sustained. Typically, you’d see the tithe go towards that, but it doesn’t.”

Tom said church leaders would ask for donations and give members a week to provide the donation. In his case, he donated around $300 in total.

On George’s second visit to the main temple in Korea, he and his mother, like other members, lined up to meet Zahng after the service. When it came time for his mother and him to go up, George was confused. Without George saying anything, the translator described to Zahng his struggles with drug abuse, and about how his father had stopped sending child support to them, and her face dropped. “It was the weirdest thing,” he said, stunned by the fact that the translator knew and was sharing such sensitive information about him with someone who—as God—he assumed would already know everything. These were things he had only told his church leader back home, under the assumption that it was confidential. He later found out that the Church reported his situation to the elder of the Church, who then passed it onto the headquarters in South Korea. He felt “violated” and disturbed that his intimate struggles were being openly discussed, just so that Zahng could tell him “everything’s gonna be alright, it will get better.”

George said that the Church frequently shared such sensitive information without members’ consent. He told us that the same thing happened to some of his friends in the Church who were conflicted about their sexuality, or were in relationships that weren’t ordained. The Church would tell George that God the Mother knew these things, because she is all-knowing, but when he questioned why Zahng even needed a translator, the deacon at his church in California told him that she’s God in human form, and that in the same way, Jesus had physical aspects that made other people doubt and crucify him. They would tell him that he shouldn’t question those things, because “God’s thoughts are higher than ours.”

Still, Zahng’s generosity isn’t fiction. During George’s visit to Korea with his mother, he learned that the Church had given his father $5,000 for child support—because he had refused to on his own—and the Church wanted to fix that relationship and ensure his father, a missionary for the Church, wouldn’t lose face. But George and his mother never got the money; they never even knew it existed until Zahng asked him about it. Zahng ended up giving them $2,000 in a brown envelope, which George felt was like an “emotional investment.” He was conflicted, because he was grateful for the money and still steadfast in his beliefs, but the money also made him feel even more tied to the Church, like he was indebted for something that he was actually owed.

“It was a very hard moment to know that he used that money from the Church,” George said. “I don’t know what it was for, maybe he just gave it back to the Church, but I felt very manipulated after finding out that she gave me $2,000 and gave $5,000 to my dad, but she’s just recycling our tithes and offerings so that they could keep us in.”

The Church’s presence on campus isn’t new. After our first article in May, we learned that students have been approached on campus since as early as 2018. One Yale student wrote on Twitter that she was approached during her first year in 2018. Although she wasn’t alone, the Church members ignored her friend who is a man, focusing all their attention on her. After she explained to them that she was a practicing Muslim and was not interested in “expanding” her views, she wrote, they tried to tell her that God the Mother “worked under all major religions.”

The members had told her that they were Yale Divinity School students and were trying to form an official club on campus. We weren’t able to identify any current or former students at Yale, besides Davornne and Ashley, who are members of the Church.

Another student wrote that he was “followed” from Cross Campus back to Bingham Hall in his first year by members of the Church. “I had to run into the entryway to escape,” he wrote.

Outside of Yale, ASEZ has chapters at the University of Connecticut, Antelope Valley College, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI), New York University, Old Dominion University, Bronx Community College, and Lehman College.

The chapter at the University of Connecticut holds active meetings, including “paint and plant” events, game nights, and general body meetings. The other college chapters nationwide are often highlighted for their service work by local news outlets, including planting trees or cleaning up local areas.

George moved back to the United States as a child and grew up attending one of the Church locations in California. “It was a part of my whole childhood,” George said. “Everyone that I knew in the Church would be considered family. I didn’t know anything else. I didn’t know how other services went at other churches or just how normal people outside my church acted.”

Each Saturday, the children would be brought to a separate room, while the adults went for services. “It wasn’t a good place for kids to strive and it’s very depressing, all we do is study the Word of God. But it was back to back, and we were just kids,” George said.

Sealed away in a room all day, he would learn to recite “Mother’s Teachings” which were Zahng Gil-Jah—God the Mother’s—thirteen teachings. For as long as their parents were in the services or Bible studies, the children were studying the teachings. This sometimes meant that they were there from 9 a.m., when the first service began, to around 9 or 10 p.m., when the third service ended, with just short breaks to go outside or eat. “We never had time to sleep,” George recalled. “If we slept, we would be woken up. We’re never able to close our eyes, we’d have to always be looking at the Bible.”

Kelsey, for a time, was in charge of teaching children on Sabbath days. She taught a group of children ages 3 to 15 for the entire day every Saturday.

“5-year-olds, I had to teach them how to find the verses in the Bible and then repeat the subjects and test them,” Kelsey said. “Children were expected to bring their classmates, their teachers, their friends and families [into the Church].”

Kelsey added that at the end of the day, she would meet with other members of leadership and was expected to divulge any issues or problems her students were facing, including things said to her in confidence.

As her role in the Church ramped up, Kelsey found that she was committing every moment outside of work to the Church. Everyday after work, she would be at the Church or around campuses preaching until around 10 p.m., then after getting back home, she would study for another two hours, and the next day she would do it all over again.

“There were no days off, absolutely no days,” Kelsey said. “I lost every single friend I ever had.”

The Church’s hold on its members extended to anything that was considered “earthly”—anything that might take you away from your heavenly family. That meant non-religious music, movies, sports, and internet use were discouraged; work was largely thought of as a means to better contribute towards the Church; and connections with family, friends, and romantic partners had to center the Church.

Less than a year after Anthony joined the Church, a head pastor had asked him how he was doing. ”You should be thinking about a family,” he said, suggesting that he marry a member of the Church.

Anthony had previously heard rumors about arranged marriages, but felt thrown off-guard. When he told the pastor that he hadn’t given it any thought before, the leader of the Church told him to “look around” and tell them who he liked. “They say that if you get married, you have a lot more opportunity to be blessed by God,” Anthony said. Anthony ended up marrying a woman the pastor first suggested in October of 2012, a year and three months after joining the Church and just a few months after their first date. They had met before, but never really spoken, and after four months, they went to different locations. After only two dates, they were told they had to decide whether or not they would marry each other.

Anthony told us he’d been asked to relocate multiple times over the decade that he was in the Church. That, in addition to the late hours spent at the Church—sometimes staying up until 1 or 2 a.m.—meant that it was difficult to maintain a stable career. In 2012, he lost a job he had worked for six years—he started messing up at work because of the late nights. Once he found a new job, the Church told him it was time to be married. On the day of his wedding, the pastor told him that he and his wife should move to Florida, but he never gave Anthony an explicit reason. Moving to Florida meant that he’d have to give up his new job, spend some time finding new work, and—because he went from a management position to an administrative position—live on half his previous wages. But he did it, because the Church told him to. He relocated three more times after that with his wife. They stayed married for nine years.

“We went through a lot of ups and downs, especially at the beginning, getting used to being married to a stranger,” Anthony said. “Looking back, being married out of fear, and out of the fear of condemnation, it definitely feels wrong for both of us. I feel like to have an expectation for somebody to marry a stranger…and doing it under threat, it’s kind of hard to express, because, in essence, you just feel like you’re forced to be in this intimate relationship with somebody that you haven’t chosen…Ultimately, you’re only doing it because you’re obedient to the Church.”

“Let me ask you this,” Victor said when we asked him if the Church conducted arranged marriages, smirking. “Let’s say you and I, we go to a party, and I introduce you to a friend of mine. ‘I think maybe you guys can make a cute couple, you want to get to know him?’ Would you say I’m arranging a marriage?”

Victor was introduced to his wife, who is Korean, by his pastor in 2009. They were married a year later. “I got to know her, and we went on a date, and we went on a few dates, we dated for some time, and then we decided to get married.”

Kelsey said that the Church showed members a verse in the Old Testament that said that Jews should not mingle with gentiles, in order to justify why members should only marry within the Church. “In the same way we are spiritual Jews, and we don’t need to mingle with the people of the outside world,” she said.

“I struggle every single day because of this church,” Kelsey said. “The Church taught for the longest time that if you ever leave the Church of God, you will die, and you will die a horrible death. So whenever something bad happens, that always comes into my mind, even though I know that what they did is wrong.”

Photo: George trip to meet Zahng Gil-jah. Courtesy of George.

Kelsey left the Church in 2017, ten years after joining. The process of leaving was difficult for her, because by that point she was utterly convinced that the end of the world was approaching. She left, not because she stopped believing in the Church, but because she was so burnt out from its demands that she realized she physically wasn’t able to keep going. She had been told that she was “lazy” and “wasn’t working hard enough.” The reason her parents died, church authorities said, was because she wasn’t preaching as much as she should be.

Her father’s death brought her some clarity. He had a stroke, and his family, after days spent living with the possibility of him never returning to consciousness, made the decision to take him off of life support. The day the procedure was meant to happen coincided with one of the Church’s feasts, but she was told she still had to be at the Church that day. “Even though I told them my dad’s dying in the hospital, and this is the day that they’re going to pull the plug,” Kelsey said. “They said, ‘Let the dead bury their own dead.’”

But by that point, ten years in, the decision to leave the Church wasn’t easy. For one thing, all of her friends were in the Church, and while the Church as an organization is “toxic,” she said, the people you interact with on a daily basis are kind people who just got “caught up in this mess.” She was torn between wanting to leave, and believing that if she left she would be condemned to hell. She decided to take a break from the Church, but when she didn’t show up for one service, she was bombarded with texts asking where she was and if she was okay, and apologizing for not having paid enough attention to her. She found out that members of her church had circled her sister’s apartment block, looking for her car. When they showed up to her work, lying to get through security, she decided she had to take a formal break. She did her research and confronted the pastor with questions she knew he couldn’t answer. The nail in the coffin: why did the Church claim that its founder was pastor Kim Joo-cheol, and not God the Father Ahn Sahng-hong, on its religious non-profit forms to the Internal Revenue Service?

Still, it took several months for Kelsey to stop believing in the Church’s doctrine. Five years on, she continues to have apocalyptic nightmares, dreams where she is being burned alive or has to watch people burn up around her. She has been told by friends and family that she has some form of Post-traumatic Stress Disorder, and she still struggles to find joy in doing things that don’t have a purpose connected to the Church, like watching TV, watching movies, or listening to music.

“I struggle every single day because of this church,” Kelsey said. “The Church taught for the longest time that if you ever leave the Church of God, you will die, and you will die a horrible death. So whenever something bad happens, that always comes into my mind, even though I know that what they did is wrong.”

In the months since our first article, we’ve wrestled with the question of what makes something a cult, and what makes a cult dangerous, as opposed to just different. We previously spoke to Steven Hassan, a cult expert, about the difference between ethical cults and unethical or destructive cults. The key difference, he said, lies in whether or not members are deceived into joining.

Having spoken to former and current members, that sense of deception is certainly there, but it’s hard to define. People are baptized almost immediately, but not all of them later regret it. Members learn about Ahn Sahng-hong and Zahng Gil-Jah at different stages. And although the Church’s members are responsible for bringing people in, no individual member is at fault for the way the Church eventually strips its members dry of their money, time, and autonomy. Victor, the spokesperson of the Church, welcomed us into the Church at Middletown without hesitation, but he was also quick to shut down any complaints from former members that we shared with him. We got the sense that that was the kind of denial members were met with when they raised questions.

College campuses have long been attractive to alleged cult organizations: the Moonies, the cult of Sarah Lawrence, Shincheonji. College students are often open-minded, but also at their most vulnerable—far from home and looking for a sense of community.

In 2018, the University of Memphis banned ASEZ from its campus because of its aggressive preaching practices. But other universities, like the University of Washington, feel that preaching falls within freedom of speech, and instead just advise students to research online or ask a friend or advisor before joining something new. Yale administrators did not respond in time to a request for comment, so what Yale might choose to do, if anything, is unclear. This semester, there’s been a marked absence of ASEZ’s presence on campus—perhaps because the last known student to be a member of it has graduated—but dotted around campus are people handing out flyers for other churches, or sitting quietly besides magazine stands of church pamphlets propped up on the street. It’s hard not to wonder what differentiates these groups from ASEZ.

For now, though, and perhaps indefinitely, Kelsey will continue to be haunted by the prospect of the world’s collapse and her condemnation by a woman living in South Korea.

—Miranda Jeyaretnam is a junior in Pierson College. Sarah Cook is a sophomore in Grace Hopper College.