The studios are easy to miss.

To find the one in New Haven, you have to go to the Graduate Hotel on Chapel Street, right across from the Yale School of Art. Walk through the doors, up a small flight of stairs and emerge into the lobby. Go past the mismatched sofas and armchairs, tacky wallpaper, and framed Yale paraphernalia. Ignore the coffee counter—even if that sharp whiff of freshly pulled espresso starts to draw you in. Go further, into the back room. Then the very back of the back room.

If you see the small gold plaque by the wooden double doors, then you’ve found it. Graduate Sweet Dreams Society, it’ll say. That’s it.

I only found it because I was kind of forced to. There was a New Journal meeting in the back of the Graduate’s lobby for the design of the previous issue, and as a God-fearing Associate Editor of this magazine, I attended. But I didn’t know a thing about design, so my eyes wandered. I looked at lamps, then students staring at their laptops, then the big double doors. Then the shiny gold plaque right next to them. I almost thought it was one of Yale’s secret societies.

A visit to the Sweet Dreams Society’s website is just about as vague as the plaque. The first thing to load on the screen is the all-seeing eye at the center, just above the words “Dulce Fomnii,” which could mean “sweet dreams” in Latin if “Fomnii” wasn’t one letter away from “somnii,” the actual word for “dream.” This could’ve been a mistake in transcription—a version of the letter ‘s’ in Old English and Roman cursive can easily be confused for a lowercase f. But to really learn about the Sweet Dreams Society, you have to move your cursor until the link to the About page presents itself in the top left corner of the screen. Turns out, my guess about the Society was close. Those big double doors are the entrance to an art studio, one of ten tucked away in select Graduate Hotels across the country.

The Graduate Sweet Dreams Society is an immersive artist-in-residence program and creative community, the website says. We’re helping emerging artists turn their dreams into a reality.

And for four months last summer, Yale undergraduate Geovanni “Geo” Barrios held the keys to Graduate New Haven’s studio and did just that, slipping behind those big double doors and that strange gold plaque.

Geo’s tools and near-finished projects were scattered around the studio in a kind of frozen chaos.

To my right: paintings and prints that I could barely make out from a dark corner. On an open shelf that split across the middle of the room: assorted blades, thick bundles of yarn, mason jars of handmade dyes. Then the floor: skinny birch trunks with the roots and branches amputated, their crowns decapitated too—really, just rough poles, bound by rope to one another in some abstract frame, a large wooden ‘X’ at its center.

I watched Geo kneel on the floor, eyeing a tail of rope that dangled from the frame. “This one’s too long,” he said, holding it up so I could see. He kind of looked like a dad with his baseball cap, cargo shorts, and a dark mustache. And it suited him, his relatively simple appearance inside this busy room, against the overall noise of the Society’s kitsch marketing. Geo’s voice was easy to follow, too—light, with a slight slowness that made his words feel more deliberate. It was the day before his capstone solo exhibition, and I think he was practicing how he would finally speak to an audience. But at the moment, we were talking about the beginning.

Last May, near the end of the school year, Geo still didn’t know what he was going to do over the summer. He’d been looking into art fellowships and other residencies, ways to spend time making art without the pressure of needing to work. This was before he found the Sweet Dreams Society. By the time he did, the application—a video proposal—was due in two days.

“Two. Days.” He repeated to me. “I saw it, and I was like, holy shit.” Any longer, and the Society would’ve slipped away, unnoticed.

Geo found the Sweet Dreams Society the same way I did: by chance, browsing in the back of the back room of the lobby of the Graduate Hotel on Chapel Street in New Haven, Connecticut. But Geo might not have found it without a little happenstance either—he didn’t have Wi-Fi where he lived, but the nearby Graduate did. With little time for planning, he grabbed his camera and recorded his application on the spot, describing a project of his that had never come to pass.

“Everyone’s an artist in some way, shape, or form. I believe.”

His government name is Paul Blair. His professional name is DJ White Shadow. He’s got blue eyes, a healthy gray beard, and several black-ink tattoos that run down his arms to his fingers. DJ White Shadow is the type of guy that looks like he’s got a story or two, and he probably does, having produced the likes of Lady Gaga’s Born This Way and Artpop, and the 2002 Yu-Gi-Oh! theme song.

More importantly, DJ White Shadow is the founder of the Sweet Dreams Society.

My first time seeing Blair is through a promotional video posted to the Graduate Hotel’s Instagram in December of 2021. He steps in front of an unassuming white background, taking a seat on an unassuming white stool. The Sweet Dreams residency, he says, is about space.

“I believe that in order to create the best product, you need to experiment with where you create. You need to be comfortable where you create. You need to create in a positive, uplifting environment.”

What matters to Blair aren’t just the spaces the artists are entering, but also the spaces they’re coming from. According to its online application, the Society seeks “artists with strong ties to the Graduate community they’re applying for.”

I found this confusing.

Graduate is a hotel chain, with each of its thirty-three locations established specifically in college towns like Berkeley, Fayetteville, and New Haven. We are all students, its tagline declares. But I wondered why the Sweet Dreams Society lives out of a hotel chain of all places, where the idea of community becomes a nebulous, even secretive thing. After all, the only people consistently around are the ones clocking in and out for work, the people behind desks and counters and in employees-only back rooms. Then, there’s the fact that Graduate hotels are college town hotels, meaning the other “consistent” presences are passersby, like visiting alums, students’ families, and tourists. And are New Haven locals also included in Graduate New Haven’s community, even without a reason to ever spend the night there?

I wondered what it meant for someone—for an artist—to be tied to a hotel community, anyway.

In any case, Geo had solid enough ties to the Graduate community as someone living in New Haven, a student attending Yale, or a guy who regularly visits the lobby to do work. Maybe a mix of everything. Looking at what had clearly been months of work in the studio—the many careful knots of rope keeping his sculpture together—Geo proved himself well. Whether it be within the Graduate or Sweet Dreams or really any other community, I think Geo does have the ability to tether himself wherever he’d like, if that was what he wanted. My question lies in how tight this tie to the Graduate community was and would continue to be, and what exactly it looked like from both sides of the rope.

The backgrounds of the rest of Geo’s cohort continue to reveal how much more pliable the criteria of community can get. Already an upperclassman on academic leave, Geo’s the youngest resident of the eight-member Summer ‘22 cohort by about four or five years. He is this cohort’s only college student. Geographically speaking, the rest of the 2022 cohort is a mix of bona fide locals, alumni of host towns’ associated schools, and total newcomers. As a whole, the Graduate and the Society’s community ties tangle into a knot.

To be fair, the Sweet Dreams Society is still young. At the time of writing, it has recently opened the application for its Winter 2023 residency, which will be its third cohort of artists. Maybe the Society’s obscurity, both in reputation and logistics, is reasonably unintentional. But I still find this interesting with a figure like DJ White Shadow in charge.

Then again, “We are all students,” said the tagline. The Society could still be learning how to emerge, too.

Talking to DJ White Shadow is like talking to a quirky uncle.

Though we were on a phone call between New Haven and Paris, I could almost hear the expressions he made as he spoke, the way his hands might’ve been waving around when he called people he didn’t name directly “boneheads,” “total turds (to be frank),” and “full of shit.” Incredibly nice guy, though.

“We’re trying to build something that’s emotional. Like, for lack of a better word, very loving and tied to our surroundings.” He went on, “The basic ethos of the Sweet Dreams Society is that hotels are in the community, the hotel has space, and all the space in the hotel should be used—preferably for good rather than evil.”

Paul laughed as he said this.

It turns out, his tie to the Graduate community is a simple one: he’s been friends with the owner for about twenty years. And so he chose Graduate’s spaces for good because they both shared the idea that a hotel should serve the community it’s in. It was an easy choice to make. Paul’s goal with the Sweet Dreams Society, then, was to serve Graduate communities with spaces that their community members could create in. That is, with a private hotel chain’s private studios, which were often discovered by chance or word-of-mouth.

Logistically, the Graduate makes perfect sense as the home of the Sweet Dreams Society. But in practice, at least in the practice of its marketing and presentation, I’m still unsure what to make of it. I remember, in particular, when Geo told me about friends who had passed by the Graduate without ever knowing he was working in a studio in the back—“You’re telling me you’ve been there? Every day, ten hours a day for the last four months, and we have never been inside?”

The studios are for their communities. Their Graduate communities, specifically. But before anyone else, the keys belong to the artists. I had asked Geo if his time working in the studio felt influenced by Yale, perhaps the most present Graduate New Haven-related community sitting outside those doors. He shook his head no.

“This is my space,” he’d said, looking over his projects and furniture and scraps of rope. He smiled.

I am still unsure of what kind of artist community the Sweet Dreams Society aims to build from the already loose bounds of what makes the Graduate community. What would actually emerge if you combined, into one communal space, all ten of these isolated and far flung studios, the three to four months of personalized work from each artist, and the depth that would come with each of their solo exhibitions?

I don’t doubt that Paul is making an honest effort. I’ve heard from Geo, and three other Sweet Dreams members, what a valuable time their residency has been in terms of their art, having a space of their own, and the validation of working with people at similar stages in their careers.

“We have a lot of interactive fabric between the artists, and we encourage them to get to know each other. I try to put people in the same room, put them on the same call, put them in the same position,” Paul explained to me, “so they know, you know, you’re not the only weirdo in the world.”

Geo held his Sweet Dreams Society solo exhibition on the night of October 15.

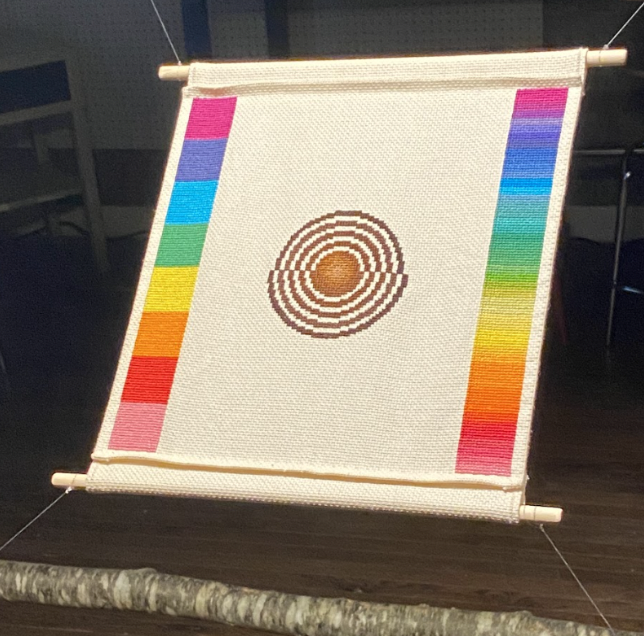

Morally Straight was set up in Graduate New Haven’s back room, as well as the inside of his studio. Geo put five works on display: “Untitled,” a series of projected AI-generated scout badges with gay epithets for keywords; another untitled piece, Scout-related archival audio layered over the sounds of the Everglades and a conversation between Geo and a friend; “The Pioneer,” a set of nine by nine foot birch frames centering a piece of embroidery; a set of three Riso prints; and “Die Faggot,” a still-in-progress flag of hand-dyed cotton yarn. His show was deeply personal, an engagement with the homophobia, nationalism, and the “dash of racism” he’s faced as an openly gay Boy Scout, an organization in which he’d spent about fourteen years of his life.

There was a lot going on. The light of the projector, the speaker’s constant music and chatter and birdsong, the sheer size of “The Pioneer” as it seemed to fill up its portion of the studio. And yet it all came together and worked, offering a place more cohesive, more open than the contradictions and liminality of the Graduate Hotel’s broader space. It was the final night in which this room was still officially Geo’s, and he did a good job of making it count. He gave an identity—his identity—to this empty space that DJ White Shadow had envisioned, somehow, as both comfortable yet experimental. There were no more secrets.

Eventually, Geo’s guests gathered around him—a fairly large group of mentors, friends, and friends’ friends. Addressing the crowd, Geo told us the story of one of the key moments that inspired Morally Straight. “I remember back when they announced the legalization of gay marriage. I was on a Scout retreat in the middle of nowhere, and we were listening to the radio. And the other boys were saying things like, ‘Hey, f*gs can marry now.’”

He paused. His voice shook as he continued, and everyone was quiet. My eyes welled up. I felt like I was listening to his diary.

“Thank you all for being here with me.”

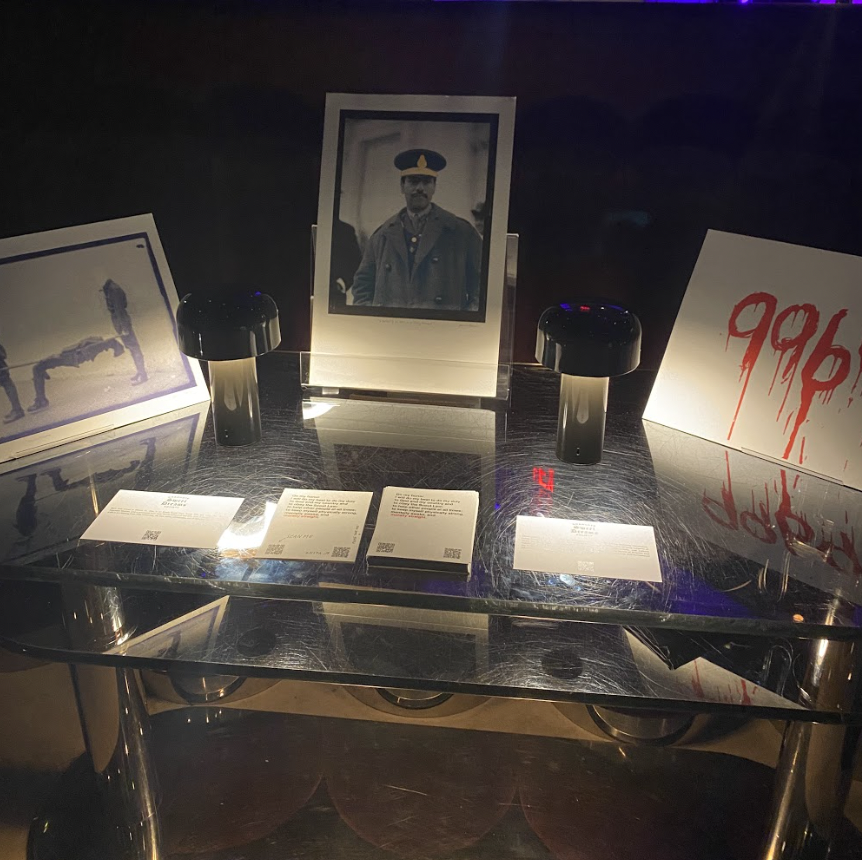

A week and a half after Geo’s exhibition was the Sweet Dreams Society’s collective artist showcase. All eight of the Society’s 2022 cohort would finally convene in New York City, in Graduate Roosevelt Island’s Panorama Room. This was where I began to realize that maybe the Sweet Dreams Society and its collective identity, at large, aren’t supposed to make much sense. But I wanted to try to understand it anyway.

The Society’s little gold plaque was almost as hard to find in the Roosevelt Island hotel as it was in New Haven—behind the receptionist’s island counter in a small cubby of a hallway. But that night, the studio doors stayed shut. I walked just a bit further to the elevator, blocked off by velvet rope and a pair of security guards. I showed them my ID and they allowed me to ascend to the top floor. The elevator opened to more velvet rope and two people with a list, taking names by the door.

I stepped into a rooftop bar. Geo’s work was the first thing I saw, but just a portion of what had been on display in New Haven: his three Riso prints on a small table and his AI Scout Badges, projected on the floor nearby. Right behind the projections was DJ White Shadow himself, working a DJ set from an elevated booth. Despite the crowded bustle of the bar and the music that was so loud that you had to yell if you wanted to talk with someone, he was cool, focused, and remarkably unnoticeable—I never would’ve guessed that he was the founder of all this.

The rest of the showcase had been set up in a long, narrow lounge annexed from the rest of the bar. There, about three to four paintings from four different artists were intimately packed together, flanking both sides of me as I walked down to look. Still wearing my puffer coat from outside, I tried not to bump into the easels as I passed by (but this would happen anyway, multiple times). Between these artists’ works, there was actually a fine amount of room. Just not enough to get the full picture of what they’d really done for all those months over the summer—not unless you put in the effort to find a closer look.

Here were the artists of the Sweet Dreams Society, finally all together in this communal and surely bonding celebratory experience. But what seemed to have happened when they were put all together, at least to me, was that their community was too tightly-woven and too distant all at once; it was incredible to see all the different things they’d put together under the same mentor and in the same chain of hotels, from fiber installations to paintings to huge papier mâché sculptures, but each had taken a little of the focus away from its neighbors, especially due to the hotel bar’s lack of dedicated space for the show. I saw a lot of the Sweet Dreams Society’s art, but I didn’t know how much I could see of the artists themselves.

Everything from that entire summer of working away in privacy was finally out in the open. But as I sat in that little lounge, surrounded now by guests who seemed like they mostly came for the charcuterie board, their complimentary drinks from the bar in hand, I wondered what all of this was really for. The celebration of the work, or the act of the party? Maybe I wasn’t tied closely enough to their community to know.

The fifth display, at the end of the lounge, had a little more room and was intended to be an experience. Yen Azzaro’s ALTAR|ALTER is based on the Buddhist shrine of her childhood home. But rather than gifts for the spirits, Azzaro’s altar was filled with items related to survivors and victims of anti-Asian hate crimes—a chunk of concrete, a knife, a target bag, a bottle of massage oil. There was also a bundle of incense for observers to “pray” with and leave in a bowl of rice. I grew up Buddhist too, and I thought this was beautiful.

Azzaro couldn’t ship the original “altar” from Michigan, so what sat in front of me was a small table from the outside lounge, with some of the items on its surface while others were relegated to the floor. Alongside those were vinyl signs with instructions on how to approach the exhibit.

ALTAR|ALTER by YEN AZZARO. 欢迎, Welcome. If fitting, please feel free to remove your shoes.

Since I was at a rooftop bar, I kept my shoes on. But either way, it felt wrong to step on someone’s words, even if I was stepping on them to pray. When I held the incense between my palms and thought about the awful things that happened to these people, and what it must’ve been like to go to a studio every day and think about it even more, I got emotional. This didn’t last very long though.

The club-style Lizzo remix booming over speakers snapped me out of it.

I was hoping to just let you in on my little world of crafts, but I was convinced by a friend that you might appreciate some footnotes.

– Geovanni Barrios, Morally Straight

Getting back to New Haven was a fever dream. An all-nighter at my cousin’s place in Queens, a 5 a.m. F train, a 6 a.m. Metro-North train, and an 8 a.m. Lyft to my 9 a.m. lecture. And the entire time, I was still deciding whether or not I knew what the Sweet Dreams Society really was yet. Even now, I’m still thinking about it.

For a residency trying to push the work of unestablished artists into the world, the Society can be an enigma to outsiders like me, with its closed doors and private studios and obscure online marketing. To really understand what goes on in those studios, you need ties to the Graduate community. Specifically, you need to have ties to individuals in the Graduate community, or you might find yourself at a rooftop bar bumping into easels and wondering what was going through any of those creators’ heads for that whole summer of being a member of the Sweet Dreams Society.

I was lucky to have ties to Geo. Since I saw his own little world of crafts before the Society would take it someplace bigger (not to mention, own the rights to those crafts afterwards), I saw what it did for him as an individual artist. He’d been given the space, time, and money to really flesh himself out, to continue emerging with an identity of his own. Morally Straight was powerful. And confessional and eclectic and distinctly Geo. I am happy that this is a place in New Haven, now, for people to go and make this kind of thing happen.

But there are still those unanswered questions for me about community. I wonder how the Sweet Dreams Society will continue to “learn as it goes” (says Paul), and how long it might take for it to emerge as the kind of community Paul wishes for it to be. I wonder, in the very back of my mind, if there was ever a concrete idea of a “Graduate community,” or if it ever was possible to carve one out in the liminal bustle of a college town hotel.

If you find yourself in New Haven, I think it’s worth stopping by the Graduate. Again, on Chapel Street, across from Hull’s Art Supplies and the Yale School of Art—down the street from the Yale University Art Gallery, if that helps too. Walk into the lobby, and for the purposes of this visit, poke around a little. Take in the kitsch furniture, the random Yale artifacts on the walls and shelves, the pizza payphone blocked off by a line of rental bikes. Go to the coffee bar, have that shot of espresso, and do some people watching. Who’s working in there that day, and how many have migrated from the back room to the back of the back room? Or did the hotel close it off for a private event?

If it’s open, definitely walk inside and look for the gold plaque. The doors to the studio will probably be locked, but they’re fun to look at when you take guesses at what could be behind them now, in the in-between of the summer residency and the winter residency to come. If it were me, I’d take guesses at what kind of person might get the keys next. I would also make guesses about the shape of the community sitting outside those doors, the community that would be sitting all around you. What are their ties here? Do they have any?

Go to the Graduate. Find the studio. Figure it out for yourself, too.

—Kylie Volavongsa is a sophomore in Silliman College and an Associate Editor of the New Journal.