1. HOME

Most of the symbolism in the office of In Our Blessed Mother’s Arms (IOBMA), a family center in New Haven, falls into two categories: babies and the Biblical.

First, the religious decor. Scattered around on surfaces and shelves, there are the miniatures: figurines of the pope, an angel, a nativity scene, a friar. Virgin Mary statues—white-glazed, gold, ivory, and blue—tower by comparison. One is knee-high.

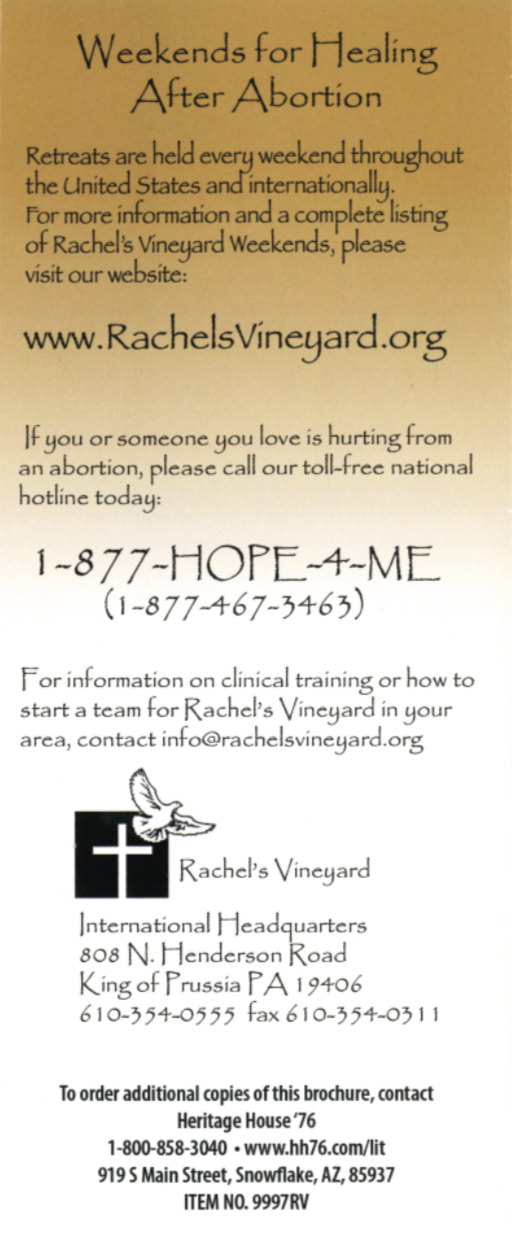

The baby paraphernalia, on the other hand, is more life-sized: there’s a baby-sized baby doll for a baby to play with, fetus-sized fetus dolls that are handed out to potential clients on the street, a brochure illustration of “a tiny person—his actual size and appearance…” in the womb. On the walls, there’s a variety of babies of different races on posters inscribed with messages like Life is Precious, Celebrate Life! and Babies are Blessing Choose Life! And in photographs populating a corkboard, there are the babies of IOBMA’s clientele.

From the outside, the office building could be mistaken for someone’s home: yellow siding, a rust-painted stoop with a little fleur-de-lis carved into the awning, ruched sheer curtains frozen behind the glass. Instead, it houses a dentist’s office on the first floor and IOBMA on the second. The next door neighbors—the New Haven Fire Department to the right, a white-pillar mansion on the left—appear less cozy. Together, the trio makes for an unlikely group: a place to deal with fire, a place to live in grandeur, and a place to deal with a pregnancy.

Ivana Solsbery, the owner and Director of the family center, sat at her desk, still recovering from her twice-weekly, two-hour prayer session outside New Haven’s Planned Parenthood. Just out the window across from her, on the other side of the street, Planned Parenthood’s THESE DOORS STAY OPEN banner drifted in the breeze.

Set against the nationally recognizable shadow of Planned Parenthood and the liberal landscape of Connecticut, In Our Blessed Mother’s Arms seems like an obscure outpost. But there are similar sites found all over the country, most commonly known as crisis pregnancy centers. Their definitions generally circle the Guttmacher Institute’s, which describes them as “organizations that provide counseling and other prenatal services from an antiabortion (prolife) perspective.” They have a few analogous labels—including pregnancy resource centers, limited pregnancy service centers, pregnancy care clinics, or, more pejoratively, fake health clinics. IOBMA is a reflection of this naming tedium: Solsbery and the center’s website call it a family center, but its Facebook page says it’s a “Pregnancy Resource and Outreach Center.” It offers services that many crisis pregnancy centers offer—and then some—and serves mostly pregnant clients. Like other centers, it does not provide referrals for abortion, and its website has a disclaimer that it’s “not a pro-abortion organization.”

IOBMA doesn’t operate like all crisis pregnancy centers in the country—by nature, they are varied and shifting. Beyond its relatively obscure appearance, IOBMA is functionally a humble operation, too: it’s a one-woman-show that usually helps just a couple pregnant clients at a time, offering resources and supplies to help clients through pregnancy and childrearing. IOBMA doesn’t compete with Planned Parenthood because it doesn’t offer abortion services, and perhaps it even helps supplement the clinic’s family services. But Planned Parenthood’s recognizability helps IOBMA more. It helps IOBMA help others.

The IOBMA office at 340 Whitney Avenue. Photos by Lukas Flippo.

2. A STATE OF CRISIS

Many of today’s crisis pregnancy centers present as legitimate clinics. But they lack the medical licensing and regulations, such as federal privacy laws, that health facilities are bound by. They don’t support abortion. If they mention abortion as a pregnancy option with clients, they don’t provide referrals—though that caveat isn’t always clear in their messaging. They often offer a swath of useful services for free, like pregnancy tests, ultrasounds, and basic supplies like diapers, cribs, and baby clothes. But these services can come at a cost, such as false information about pregnancy and the risks of abortion, required parenting coursework in exchange for free services, the failure to provide diagnoses or accurate readings of ultrasounds, and, crucially, clients’ time—with the potential consequence of delaying prenatal care, sometimes until it’s too late for a legal abortion to be an option.

Tracing back to the sixties, these clinics have historically served clients who are primarily low-income, young, and people of color with friendliness, family services that address some of their clients’ real needs, and a medical posture to boot. They have a legacy of persuading clients to carry their pregnancies to term with white women at their helm.

Abortion has been legal in Connecticut since 1990. But, in anticipation of the overturning of Roe v. Wade this June, Connecticut enshrined legal protections for out-of-state abortion seekers. Those provisions were set in May, just a few weeks after the Dobbs decision was leaked, in House Bill 5414, which also expanded the pool of providers who can perform abortions and shortened abortion wait times to two weeks. This bill now makes Connecticut one of two “safe harbor” states in the country, alongside New York, which passed similar legislation in June. One Connecticut abortion clinic—Hartford GYN Center in Bloomfield—has since seen patients come from states as far as Ohio, Tennessee, and Texas, according to Roxanne Sutocky, the clinic’s Director of Community Engagement.

Across the US, estimates of the number of crisis pregnancy centers range anywhere from 1,500 to 5,000—the data isn’t reported by states, the centers, or otherwise collected in a streamlined way. We at least know that they vastly outnumber the 807 abortion clinics in the US reported by the Guttmacher Institute. That imbalance will grow as the number of clinics continues to shrink post-Roe and the demand for crisis pregnancy centers subsequently grows. In Connecticut, there are at least twenty crisis pregnancy centers, compared to fifteen licensed abortion clinics. A given crisis pregnancy center might have a few revenue streams: donations, national anti-abortion organizations that fund and direct thousands of affiliate centers, and—though not in Connecticut—state tax dollars. Nationwide, crisis pregnancy centers receive five times more funding than legitimate abortion funds and clinics. They’re typically 501(c)(3) nonprofits, which means they qualify for federal income tax exemptions, and their tax returns don’t have to be public. This means they can often offer their services for free. Many centers open locations near abortion clinics, college campuses, and in low-income neighborhoods.

Roxanne Sutocky told me that, between the network of abortion clinics she works with in Connecticut as a Community Engagement Director for The Women’s Centers (which includes Hartford GYN), patients tend to encounter crisis pregnancy centers in some capacity before coming into contact with a legitimate clinic. In part, that’s because they are some of the top hits that come up when you search terms online related to pregnancy or abortion options in Connecticut. “We hear people coming to us and regurgitating the misinformation that we hear from anti-abortion centers,” she said. “It’s unfortunate because, for many people, it’s very unclear to them that the person that they’re engaging with or the website that they’re looking at is actually an anti-abortion entity.”

In Greater New Haven alone, there are at least four crisis pregnancy centers besides IOBMA—there’s Mary and Joseph’s Place in North Haven; Birthright of Greater New Haven in Hamden; Carolyn’s Place Pregnancy Care Center located across the street from Waterbury Hospital; and Saint Gianna Pregnancy Resource Center, which operates out of a mobile van and a building nestled next to the New Haven Hospital Saint Raphael Campus in New Haven’s Dwight neighborhood. Meanwhile, there’s only one licensed abortion clinic in New Haven. And it’s IOBMA’s neighbor.

3. LIKE MOTHER

“I knew in my heart that one day I would be doing this,” said Solsbery, with a gesture around the office. “Because I came from where they’re at.”

She’s talking about her clients—pregnant mothers seeking help in this den of religious and infant paraphernalia. But those clients are hard to find. I tried reaching out to IOBMA clients for this piece, but wasn’t able to talk to them—because of a discomfort with speaking publicly, because the office was empty, or because Solsbery wanted to protect their privacy, citing legal binding by the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). (By definition, as a medically unlicensed clinic, IOBMA is not bound by HIPAA).

In 2014, Solsbery founded IOBMA as a 501(c)(3) nonprofit pregnancy resource center at 340 Whitney Avenue. A Catholic, Solsbery was sixteen when she had her first child and struggled to find resources to help her navigate single motherhood, which she said were less plentiful back then.

Now, she’s a great-grandmother—and thanks God she had her child, because she had to have a hysterectomy at age 21. “That’s why I always say people regret abortions, but they never regret a child,” she said.

Ivana Solsbery’s got blue-green eyes, long blond hair, and she’s light on her feet. She treads calmly, to the tune of utter cacophony—a medley of syncopated key jangling, colliding rosary beads, and a cell phone that rings every ninety or so seconds. It’s usually spam, sometimes business. She puts up with the noise, maybe even likes it—in fact, she’s working on setting up two more phones in the center soon.

It’s hard to imagine Solsbery doing her job in the quiet. That would mean staying still, or putting down her things. Solsbery’s role at IOBMA is anything but a traditional, stationary desk job. Her other titles might be informal, but she simultaneously does the work of a recruiter, client counselor, fundraiser, volunteer coordinator, treasurer, and delivery service driver, among others. She’s on the go.

“We gotta keep it moving,” she said. “If they need something, whatever it may be, we do our whole power to get it done…We’ve never not gotten it done.” Solsbery told me she ends up doing a lot of the IOBMA work alone, but she often describes her work using the “we” pronoun, not an “I”. Perhaps she doesn’t give herself enough credit, or perhaps the “we” is more figurative. Still, she said she keeps some things separate from the “we.”

“I don’t push my religion on anybody,” she said. “All I’m here to do is to try to help.”

That’s Solsbery’s articulation of her mission. The IOBMA mission statement on its website is more specific: As the Lord’s purveyor of hope and the Mother’s helpers, our mission is to love mothers and children, make them our friends for life, and end abortion.

On the latter point of the IOBMA mission, Solsbery said, “We don’t refer for an abortion.” Still, she explained, “that doesn’t mean that we don’t talk about it, don’t discourage it or anything. That’s up to the individual. All we do is give the truth. They want it, they can come. If they don’t, that’s their choice also.”

But what are Solsbery’s personal beliefs about the truth? Here are her main points about abortion:

- “It’s like a cancer in our world that’s spreading everywhere.” (The national rate of legal abortion has declined steadily since the eighties, according to the Guttmacher Institute, except for an eight percent increase in 2020.)

- “For me, rape is a very very evil act done to an individual, but abortion’s evil also, so you’re going to hurt this person two times?” (According to the American Psychological Association, being denied an abortion has a greater impact on mental health than receiving a wanted abortion.)

- “You have another separate human being inside you that doesn’t give you the right to kill it, it just doesn’t. I mean that’s more brutal than African Americans being enslaved to all of this Holocaust—this is more than any war, more human beings.”

- “There’s been a lot of women who have died from [abortion].” (The mortality rate for legal abortion in the United States is 0.7 deaths per 100,000 procedures. By contrast, the maternal mortality rate is 23.8 deaths per 100,000 births, as of 2020, according to the Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The maternal mortality rate for non-Hispanic Black women is 55.3 per 100,000.)

“I don’t know, that’s my opinion,” said Solsbery.

Solsbery has her beliefs. She said she’s upfront with clients that she’s Catholic, but that it’s “not an issue at all…because we’re just here to help and they know that.” Her beliefs about abortion don’t disrupt the IOBMA operation: “We set them down and show them their options, from abortion to medical.” But Solsbery also explained that “it’s sad that our society…can’t see life within the woman, and it’s not her choice—I’m sorry, she has another individual in her now, the child’s in the world because she’s in the world.”

Still, Solsbery said she has helped fund abortion for at least one client in the past. But neither the center’s website nor the blue brochure distributed on the sidewalk advertise that IOBMA offers anything about abortion—information, funding, referrals, or otherwise. The services that the center does advertise online include housing, emergency food and transportation, financial and legal aid, pre-natal care, baby supplies,

post-abortion programs and support, adoption information, and sexually transmitted disease education. Solsbery said she also helps pay utility bills and rent, as well as find babysitters and jobs for clients. Most of her clients are pregnant, she said, and the number she’s working with at a given moment can usually range from one to seven.

There’s another service, which makes up the second half of the mission statement of IOBMA. Solsbery said it comprises most of her work, and that it’s “what’s different between our center and a lot of them”:

Another part of our mission is to deliver our Lord’s message of life over abortion to the most needy and vulnerable communities. We do not wait for these women in need to come to us; we go to them. In Our Blessed Mother’s Arms actively reaches out to these women through our grassroots outreach program and takes God’s message of love and assistance directly to them.

In practice, we go to them is pretty literal: Solsbery drives directly to the doorsteps of her clients in New Haven, Waterbury, Meriden, Hamden—“all over here.” While recruitment happens outside Planned Parenthood, Solsbery’s grassroots outreach happens from behind the wheel, with a trunk full of diapers, food, and other supplies. The clients she hasn’t already met on the sidewalk by Planned Parenthood usually hear about IOBMA through the recommendation of past clients. They often call without coming in person to IOBMA. This way, she said, her clients don’t have to pay for bus tickets or gas. Most of her descriptions of trips to help clients involve delivery of basic provisions for infants.

“I’ve been out at 10 o’clock delivering formula,” said Solsbery. “The baby had diarrhea and went through the diapers, I came and delivered them to ‘em.”

Solsbery seems proud of her work with New Haven’s refugee and immigrant communities. She mentioned a couple from Afghanistan, another from Iraq. She spoke about a girl from China, pointing to a photo of a family in a dining room on the wall of her office. “This little girl was almost aborted, but—and they’re very intelligent people—they were scared,” she said. “In their country at that time they could only have one child.” (New Haven’s resettlement agency, Integrated Refugee and Immigrant Services (IRIS), doesn’t send its clients to crisis pregnancy centers in New Haven, according to Nika Zarazvand, a Health Coordinator at IRIS. Solsbery said she mostly meets these clients on the sidewalk outside Planned Parenthood.)

Solsbery switched IOBMA’s label from a pregnancy resource center to a family center four years ago, and maintains that it’s still a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization. The change was made to reflect the center’s expansion from strictly motherhood-related services to food, housing, and beyond—as well as the aim of the organization to “unite families,” Solsbery said, and to “involve the whole family” with pregnancies.

“I’ve had dads cry on my shoulder because they didn’t want to have this abortion, but he had no choice in the matter,” Solsbery said. “He’s the father and our laws haven’t even caught up with that, and I feel so bad…He wants to do what’s right and he can’t.”

In veering away from the medical front of other crisis pregnancy centers, IOBMA perhaps becomes more appealing. Not only does it appear professionally homey, it promises a personal and long-term relationship with clients, with an all-in-one owner-recruiter-counselor-financer point-person who guides patients by the hand, each step of the way. By contrast, Connecticut’s only state-level abortion fund, the Reproductive Equity Access Choice (REACH) Fund, provides a markedly impersonal service in order to protect patients’ privacy and decision-making processes. For Jessica Puk, Board President and Co-Founder of REACH, “it’s enough just knowing that we helped people get their healthcare.”

A long-haul, one-on-one, one-stop-shop—IOBMA makes a bigger promise. And perhaps the biggest part of that promise: it’s free. Solsbery said she funds the many services of IOBMA through individual donations, and events like church drives, baby bottle drives, a biannual fundraiser by a young women’s group at Branford High School, and an oyster festival in Milford where she planned to sell some snow cones. “I’m always doing some kind of fundraiser,” she said.

She said she’s also constantly applying for and requesting grants from local ministries, such as the Archdiocese of Hartford, and wherever else she can find funding. IOBMA’s Form 990—its income tax form, obtained online—from 2014 was the only publicly available record of IOBMA spending that I could find. It shows that the center received just under $11,000 that year in “contributions, gifts, grants, and similar amounts,” which made up all its income. The largest listed expense was the “provision of diapers, lotion, formula creams and necessities for mother & babies,” amounting to almost $2,300, followed by “clothing, bedding, high chairs, car seats for babies as needed,” at around $1,000, then “printing, publications, postage, and shipping” at $950, and “supplemented food for families of clients as needed” at about $700. No rent is listed as an expense.

It’s about the family unit, not a medical practice; Solsbery claims clients’ decisions to seek abortions is respected and discussed, rather than totally rejected; it’s a local, home-grown organization funded by Solsbery pulling herself up by her bootstraps and finding funds in her community, not some direct overhead fund, and it doesn’t invoke the name recognition of a major crisis pregnancy center network like Birthright, which has seven locations across Connecticut and at least hundreds nationally. In Our Blessed Mother’s Arms, maybe, isn’t like the typical crisis pregnancy center.

Or maybe it is. What’s atypical about IOBMA makes it somewhat standard: crisis pregnancy centers all around Connecticut and the country have their own individual identities, formed through variations in geography, resource offerings, homeyness, professionalism, basis in faith, and commitment to long-term relationships with clients. Connecticut’s crisis pregnancy centers deploy via mobile van, juxtaposition with abortion clinics, and nestle in some of the state’s lowest-income regions like Bridgeport, Waterbury, and Cheshire; they offer different combinations of pregnancy tests, ultrasounds, couples’ counselling, information about abortion and adoption, and parenting counselling, among other offerings. IOBMA has filed its tax returns under the family services category, not reproductive health care, but other crisis pregnancy centers in the state file under alternative categories too, like human services, women’s services, religion, and maternal and prenatal health.

IOBMA’s also a former affiliate of Heartbeat International, one of the nation’s largest crisis pregnancy networks, according to Solsbery and a certificate in her center that indicated the affiliation expired in 2016. Solsbery’s working to get funding for an ultrasound machine from the Knights of Columbus, the world’s largest Catholic fraternal service, whose global headquarters is located in New Haven. The organization will hopefully match the funds she raises for the machine through their designated program for purchasing ultrasounds for crisis pregnancy centers. Solsbery said she hopes to find a doctor who will operate the machine.

4. LIKE YESTERDAY

In Tiny You: A Western History of the Anti-Abortion Movement, Jennifer Holland—an author and University of Oklahoma professor of history specializing in abortion history—traces the early modern anti-abortion movement with a focus on the American West, where many of the country’s first crisis pregnancy centers sprang up in the sixties. It’s also where Solsbery—born in San Diego and later spending time in Colorado—said she spent her life before moving to New Haven at the turn of the century.

Back then, according to Holland, most crisis pregnancy centers were led by either evangelical Christians or Catholics—with evangelical Christians believing in proselytizing the immorality of abortion to clients, and Catholics focusing on prayer without preaching. And within these denominations, staff were historically mostly white women. Unlike men, women could uniquely convey “that it was their experience as women that led them to their anti-abortion stance, not partisan politics,” Holland writes.The position and status of white women gave them “the experiential authority to speak to other women and the moral authority to intervene in intimate familial issues.” Beyond professionalism and medical posture, many centers sough to create a “kitchen table feeling” while interacting with clients to personalize the experience as much as possible.

Solsbery carries on these founding traditions, including the old Catholic approach—recruiting with prayer because “that’s our way of helping,” but she doesn’t expect her clients to share her religious views.

IOBMA also contains many of the shifting strategies of crisis pregnancy centers—especially the focus on the fetus, a notorious and foundational tenet of the modern anti-abortion movement used to convey that fetuses constitute human life and that abortion is murder. In IOBMA, there’s fetal development chart lining the wall in her center’s bathroom, there’s a seven-minute video on DVD showing fetal development in the womb, and there are fetal dolls that she tucks into the palms of potential clients on the sidewalk (“for when we don’t have time” to explain, she said), and Solsbery herself resists language referring to the fetus.

“The child in the womb,” explained Solsbery, “is a child. It’s not a fetus. It’s not a baby.”

In the late seventies, according to Holland, people running crisis pregnancy centers realized that the kitchen table strategy was not enough because they were largely serving low-income women, young women, and women of color who faced practical challenges that moral guidance couldn’t answer. They increasingly began offering family support services to supplement their messaging. Today, IOBMA, as a family center, still embodies this emphasis on support, and its grassroots outreach program perhaps takes it to new heights.

“White women activists asserted their moral authority by claiming to have special access to universal truths,” writes Holland. “And they tried to use that moral authority to transform the women of color, poor women, and young women who were the majority of the clients at [crisis pregnancy centers].”

By the eighties, family support services weren’t producing the results crisis pregnancy center leaders desired for the amount of effort and resources they required. So they sought to focus on the client as well as the fetus. Abortion didn’t just hurt the fetus, it hurt the client, too. “Abortion-seeking women were no longer just victims of coercion or poverty,” writes Holland. “They were victims of abortion itself.”

Anti-abortion activists began using the term “post-abortion syndrome,” which claims that abortion causes post-traumatic-stress disorder-like illness. Diagnosis was loose, so almost anyone who had an abortion could be told they had a clinical condition attributable to the fact that they terminated a pregnancy. The American Psychological Association (APA), the Journal of the American Medical Association, and similar organizations have never recognized the condition—meanwhile, the APA asserts that carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term increases risks for mental health and domestic abuse. But post-abortion syndrome still holds firm in all kinds of crisis pregnancy centers today.

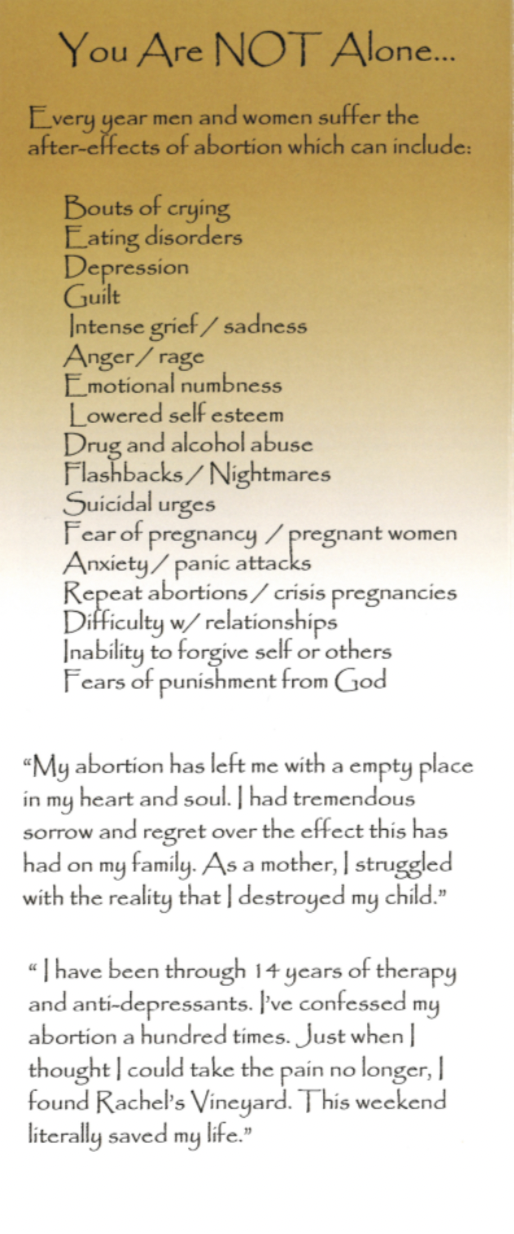

IOBMA is no exception: it offers “post-abortion programs and support” on its website and, on at least one visit, there was a booklet on-site with guidance for “Identifying and Overcoming Post-Abortion Syndrome.” Solsbery even had a brochure for Rachel’s Vineyard, a weekend retreat program she said at least one of her clients has attended, with the slogan healing the pain of abortion—one weekend at a time. The program is offered at locations around the globe in both Catholic and non-denominational settings. The Connecticut outpost is in Farmington.

Between kitchen table domestic quaintness, family values imbued through family services, and the creation of post-abortion syndrome, Holland writes that anti-abortionists “made the supposedly intrinsic knowledge of fetal life central to the female experience” in crisis pregnancy centers. Though it was founded in 2014, and is a long way from Solsbery’s home and those founding crisis pregnancy centers on the west coast, there’s a time capsule of crisis pregnancy center tactics threading through IOBMA’s philosophy and practice. The history lives on.

And now, Solsbery said she is feeling hopeful about the Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade. “Look how many lives are going to be saved,” she said. “The schools are decreasing because of abortion.” In the first hand motion she’d made in an hour, she pressed her two hands down hard on top of each other on her desk. “This is facts.”

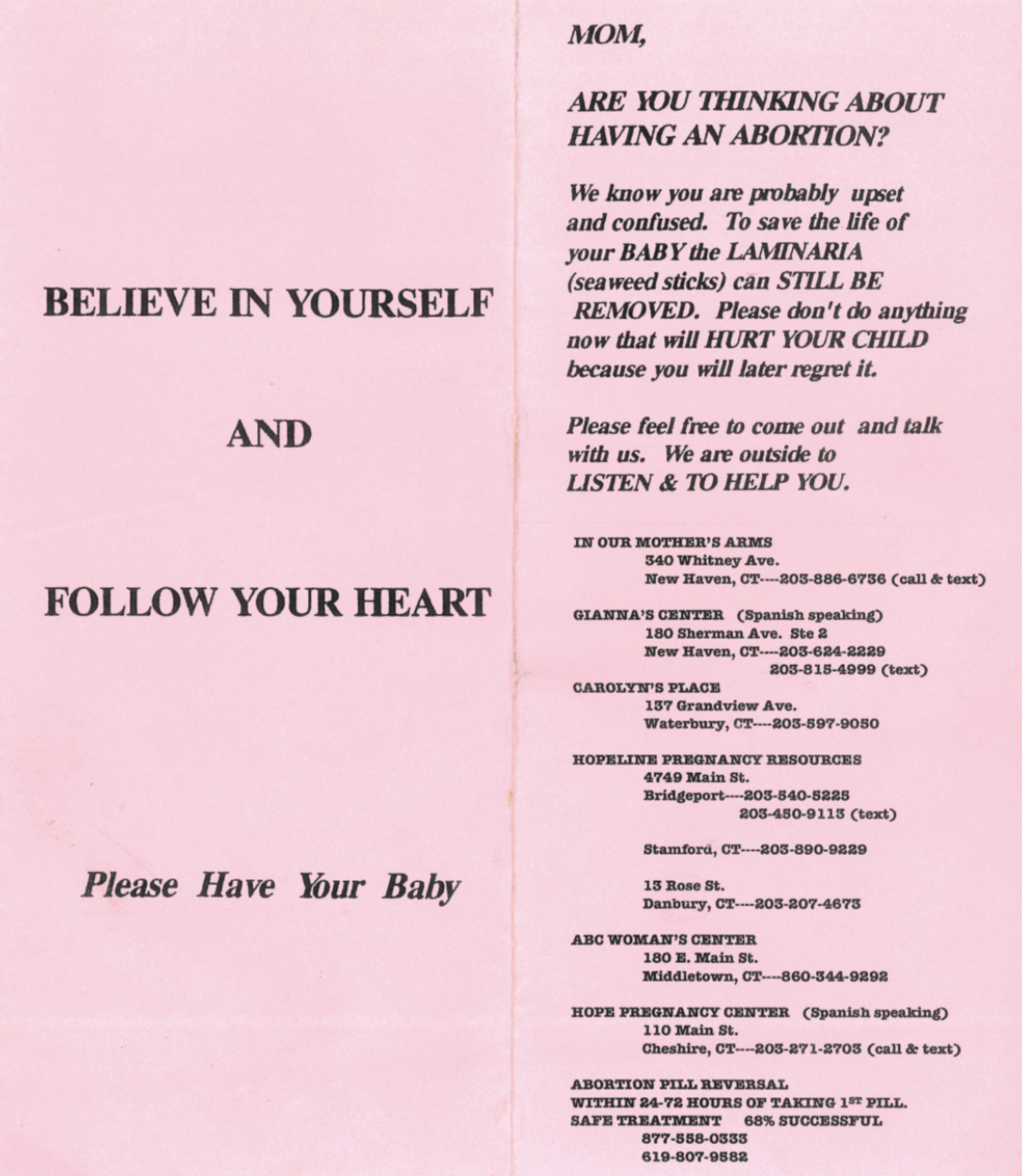

Brochure covers from the IOBMA office (obtained in August 2022.)

5. FULL CIRCLE

Up until November, the IOBMA recruitment formula was a matter of summation. On an August 12th visit, the props added up: six homemade dangling rosaries, five pairs of sunglasses, two portable stools for those who don’t stand for long stretches, one plastic grocery bag filled with brochures, seven lawn signs plugged into the grass. The result: one prayer circle straddling the sidewalk outside Planned Parenthood. It set the stage for a seemingly infinite recitation of the Rosary.

Prayer kept to a schedule: 10:00 a.m. to 12:00 p.m., Wednesdays and Fridays, each with a different set of prayer regulars. Members of the Friday group said they are part of the same church—Saint Mary’s Church in Clinton, Connecticut. On the Fridays I visited, the attendees dangling rosaries with Solsbery weren’t official volunteers or employees of the clinic—they just prayed, and maybe distributed some literature. The other helpers were the lawn signs: LIFE styled in the Game of Life font, ABORTION STOPS A BEATING HEART, PRAY TO END ABORTION, 64,000 US LIVES LOST (except the 4 is a 3 that’s been x-ed out by hand with marker), a painting of the Virgin Mary. But the real key to the equation, it seemed, happened when the circle broke. That sweaty day in August, one attendee, visibly the youngest, spearheaded the interruption.

At first, she just seemed distracted. In between utterances of Hail Mary and pray for us sinners now, her eyes lifted from the scripture, past the vortex of the circle. Something caught her attention—then, more darting glances, a nudging of her neighbor. A mumble was exchanged, a decision was made. Someone shoved a pamphlet into her hands, and she started walking towards a young woman at the stoplight at Whitney and Edwards Street, headed away from Planned Parenthood. En route, her walk broke into a jog. Solsbery tagged behind, with even more urgency and more pamphlets. Later, Solsbery told me that the woman they stopped was pregnant, that she seemed interested in IOBMA, and that she said she’d stop by. Back on the sidewalk, prayer resumed.

When first looking for Solsbery’s prayer circle in August, I accidentally approached a different group stationed at the Planned Parenthood sidewalk, on the other side of the parking lot. There, a woman handed me a brochure with more blatant messaging than the one Solsbery distributed. Where Solsbery’s asked Pregnant? Worried?, this one straightforwardly implored PLEASE HAVE YOUR BABY. Where Solsbery’s included a drawing of a fetus, this one was more photographic, with an insert displaying HUMAN GARBAGE—fetus corpses in a trash can. Where IOBMA offered alternatives to abortion, this one pleaded To save the life of your BABY the LAMINARIA (seaweed sticks) can STILL BE REMOVED.

But both brochures featured the same list of six crisis pregnancy centers in the Greater New Haven area and an abortion pill reversal hotline. IOBMA is the first on that list.

“They’re more vocal,” said Solsbery, referring to the other group. “We do the quiet approach.”

IOBMA’s sidewalk recruitment is getting quieter, and getting centralized. Solsbery recently applied to and began a partnership with Sidewalk Advocates for Life—an organization with the mission statement To train, equip, and support communities across the United States and the world in sidewalk advocacy: to be the hands and feet of Christ, offering loving, life-affirming alternatives to all present at abortion facilities, thereby eliminating demand and ending abortion. The organization currently operates 239 sites nationwide, and is helping train new volunteers to revamp the IOBMA prayer sessions outside Planned Parenthood. Solsbery said she realized that the old method was “intrusive,” and she wanted to make her sidewalk presence more approachable.

When I visited in November, Solsbery had already gained a new uniform and a goodie bag: a Sidewalk Advocates-branded blue traffic vest, and a pink-clothed sack containing Bath & Body Works lotion alongside some brochures. A few hundred feet away, in the middle of the parking lot, Planned Parenthood’s escorts stood empty-handed in neon pink traffic vests.

Going forward, prayer will be moved further away, to the other side of Edwards Street, while Solsbery will recruit alongside Sidewalk Advocates-trained volunteers where prayer happened. Solsbery said she’ll be distributing some additional literature: business cards for hotlines—Love Line and Option Line—that connect callers to local crisis pregnancy centers. The signs are coming down, too, and being replaced by a single sign advertising the link and hotline of the Abortion Pill Rescue Network. Abortion reversal—advertised as a counteracting treatment to medication abortion—is based on “unproven and unethical research,” according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, the nation’s leading organization of reproductive health clinicians. The Abortion Pill Rescue Network and Option Line are both programs of Heartbeat International, one of the largest crisis pregnancy center networks in the country.

The new recruitment strategy is showing results already. Solsbery’s barely tried out the new methodology, but more people, she said, are stopping on the sidewalk than she’s seen in a long time.

6. NO HARM, NO FOUL

Crisis pregnancy centers have strong free speech protections. Laura Portuondo—a Fellow with the Program for the Study of Reproductive Justice at Yale Law School and an advisor for the Law School’s Reproductive Rights and Justice Project—explains it this way: the Supreme Court has “essentially tied itself into knots” to protect crisis pregnancy free speech. These protections were bolstered back in 2018, when the Court heard National Institute of Family and Life Advocates (NIFLA) v. Becerra—a lawsuit filed by one of the nation’s largest crisis pregnancy center networks—in response to a law passed in California requiring crisis pregnancy centers to post information about state-offered abortion and contraception services, along with a notice that they are medically unlicensed. NIFLA argued that the government violated their right to free speech. The Supreme Court agreed, striking down the law in a 5–4 decision. Before the time of NIFLA v. Becerra, crisis pregnancy center speech was more so regarded by the Court as the commercial speech of an operational business. Now, the Court regards it as “traditional speech, like you or me,” said Portuondo. And this speech is much harder to regulate.

Still, Connecticut has attempted to regulate it, following in California’s footsteps. In 2021, Connecticut passed a bill targeting deceptive advertising and created an avenue for reporting it through the Attorney General, who can then determine if it’s deceptive and open a court order to have it taken down. Deceptive advertising, as the bill puts it, constitutes “any statement concerning any pregnancy-related service or the provision of any pregnancy-related service that is deceptive, whether by statement or omission, and that a limited services pregnancy center knows or reasonably should know to be deceptive.” The bill has limited some online advertising, according to State Representative Jillian Gilchrest (D-West Hartford), a co-sponsor of the bill, and otherwise cracking down has been a game of “cat and mouse.” And there’s still the caveat that “there can be crisis pregnancy centers who might be misinforming individuals who actually enter their physical space or who have misinformation in the physical space.”

Connecticut’s advertising bill is being challenged by the Alliance Defending Freedom (ADF), the same organization that defended NIFLA in the California case, and that helped draft and defend the Mississippi legislation that led to the toppling of Roe v. Wade. ADF filed a federal lawsuit against Attorney General William Tong, on behalf of the Care Net Pregnancy Resource Center of Southeastern Connecticut using a similar interpretation of the First Amendment to the California case.

Liz Gustafson is the State Director of Pro-Choice Connecticut, a non-profit that works to protect and expand reproductive freedom in Connecticut, and that collaborates with similar organizations across the country to engage nationally with its mission. She’s also a former escort for Hartford GYN, an abortion clinic that used to share a parking lot with a crisis pregnancy center. Liz Gustafson said that the legal backing of crisis pregnancy centers crystallizes their critical role in the anti-abortion movement.

“[Crisis pregnancy centers] fundamentally operate as the frontline for the anti-abortion movement, so while they may be operating in some kind of different way, all of them move right into the same courtyard,” said Gustafson. And if crisis pregnancy centers weren’t the frontline, she asked, “then why is the legal arm of the anti-abortion movement challenging our Attorney General legally?”

Crisis pregnancy centers seem to exist at a remove from legal and political realms of the anti-abortion movement, despite serving it, in part because they have largely been unbounded by legal responsibility for communicating accurately to clients, in part because appearing nonpartisan helps them recruit clients. These factors combined have helped crisis pregnancy centers work to change minds and hearts about abortion in as personal a means as possible.

For Dina Montemarano—who studies disinformation in the anti-abortion movement as the Research Director for NARAL Pro-Choice America, a large nonprofit national organization that leads lobbying, political action, and advocacy efforts to protect reproductive freedom—of all the ways that the anti-abortion movement spreads disinformation, crisis pregnancy centers might be the most severe: “meeting people face to face at a time when they desperately need someone who they can trust, who can give them correct information—in some way that’s the cruelest way that [the anti-abortion movement] is spreading that disinformation,” she said.

Crisis pregnancy centers have honed and shifted tactics over time to persuade pregnant women to carry their pregnancies to term. Meanwhile, legal challenges to abortion have shifted strategy in the context of what can be argued as constitutional. IOBMA has narrowed in on family services that address real, important needs of families—but that is an approach crisis pregnancy centers have used for decades to target low-income women and women of color.

IOBMA’s family focus, and its lack of abortion service advertising, make it seem relatively mild in a sea of crisis pregnancy centers that present as Planned Parenthood-like medical clinics. In the eyes of the law, it’s pretty clean. But that doesn’t change that, while its operation provides real and necessary services in the process of delivering our Lord’s message of life over abortion to the most needy and vulnerable communities, it’s part of the center’s particular mechanism of a broad mission to end abortion. This means that IOBMA might be quite helpful for pregnant clients who know they’d like to carry their pregnancies to term, especially because IOBMA’s services are free. But for clients who might otherwise have decided to have an abortion, IOBMA could be dissuasive. And now, by recently gaining an ultrasound machine and deprioritizing prayer on the sidewalk, IOBMA is partially sacrificing its non-medical appearance in favor of approachability, potentially to the effect of dissuading those clients who might have otherwise sought out medical expertise and an abortion.

Liz Gustafson recognizes the value of the services of crisis pregnancy centers in spite of their stances on abortion. “The provision of free resources is important, right? Because obviously there is a gap in terms of people being able to acquire the resources that they need, like free diapers,” said Gustafson. “That doesn’t negate the fact that they are still a component of the anti-abortion movement. I think, if anything, that should be an opportunity for our local and state government to fill in that gap. Of course, we don’t want these organizations who are perpetuating dangerous misinformation and also just stigma and shame and just terrible, inaccurate information, but also we need to make sure that people who need free resources are able to get those resources.”

Solsbery works hard to fund, deliver, organize, and execute her services. At Thanksgiving, she drove approximately forty turkey dinners to families in and around New Haven. “They were people in need,” she said. “And that’s what I’d hope that Planned Parenthood would realize someday: that if they’re for choice and the woman that chooses life, how come they don’t help her?”

New Haven’s Planned Parenthood doesn’t deliver turkey dinners, but, in addition to offering abortion and abortion referrals, it offers adoption services, adoption referrals, fertility awareness education, pregnancy options education, pregnancy planning services, birth control, emergency contraception, pregnancy testing, and trained staff to talk with patients who’ve experienced early pregnancy loss, or miscarriages. These cost of these services is low, if not free, through Medicaid, and other health insurance programs, and Planned Parenthood’s subsidization programs.

Connecticut also offers, as a part of its Medicaid public health coverage, Health Care for Uninsured Kids and Youth (HUSKY) Health. The program subsidizes health services either at low cost or for free—depending on income—for children, parents, relative caregivers, and pregnant people, among others. Undocumented immigrants are eligible for HUSKY coverage for prenatal care; children up to age nineteen qualify regardless of family income. There’s also the REACH Fund, Connecticut’s first state-level abortion fund, which started partially funding abortions this fall using a $50,000-and-growing fund. There’s other nonprofits that help with basic childrearing necessities, too—like Connecticut Diaper Bank, which delivers 300,000 diapers to 6,400 families in the state each month. IOBMA is far from the only alternative to getting an abortion at Planned Parenthood. While IOBMA has the guarantee of free services, it’s up against some robust competition and affordable avenues to obtain them—many of which are bound by privacy laws and rigorous standards of professional qualifications.

Despite Connecticut’s resources, however, US Census Bureau Data consistently shows that Connecticut is a state with extreme wealth disparity. And there will always be those who don’t have insurance, or who don’t know all the options available, or times when government support isn’t enough. And perhaps IOBMA will be there for them.

Solsbery’s concerned with the truth, and the women she says are being deprived of it. “It should just be about being truthful with each individual,” she said. “They have the choice in the end—not me, not you. Whoever’s in this situation, they have the choice in the end, but if they know all of their choices—there’s many out there, really—then that still becomes free will. God gives us free will, so that becomes that person’s free will. But if they’re not told the whole truth, no, that’s not right.”

The anti-abortion movement has evolved into an amalgamated giant over the last fifty years, and through it truth has remained a moral fact bolstered by false information. Reflecting this central truth of the anti-abortion movement—that abortion is wrong—through the prismatic lens of In Our Blessed Mother’s Arms’ many helpful services, that helpfulness seems more sinister.

IOBMA comprises one woman working with one pregnant client at a time, in a state with some of the strongest guarantees of abortion rights, in a city with services supporting access to reproductive care. Solsbery has helped at least one client fund an abortion, and she’s not interested in proselytizing. It seems harmless. But IOBMA doesn’t exist in a solitary vacuum: it builds on the wisdom and resources of generations of crisis pregnancy centers created to persuade clients to carry pregnancies to term. The delicate, hodgepodge, homemade quality of IOBMA reflects a powerful lifeblood of the anti-abortion movement: white women with a cause and the maternal approachability to persuade. The mission, after all, is to end abortion.

7. FOR THE ROAD

Back at Planned Parenthood, Ivana Solsbery is doing her sidewalk circle duties. It’s September, and the wind’s got a bite. There’s talks in the group of getting an abortion pill reversal sign soon, but for now recruitment is still happening the old way—the spotlight’s on prayer, signs, and the rosary.

Mid-prayer, the wind knocks over a sign. A few minutes later, someone riding a bike knocks over another, mumbling something. Both times, the signs are immediately put back, with a similar urgency to the literature distribution jogging.

“There you go. That’s the other side,” said Solsbery, with a sigh, to no one in particular.

Election season’s on the horizon, too, and one of the prayer attendees is wearing a Leora Levy cap. On the car next to her, there’s a Leora Levy sticker. In the trunk, there’s a Leora Levy lawn sign. In November, Leora Levy—the Connecticut Republican Senate candidate endorsed by Trump—lost the Senate race.

At one point, Solsbery’s attention turns to the Planned Parenthood escorts in pink traffic vests in the middle of the parking lot. She’s flabbergasted.

“Why would anyone volunteer to do that?” she asked.

—Nicole Dirks is a junior in Branford College and Co-Editor-in-Chief of The New Journal.