In John Cavaliere’s shaky iPhone recording of a late-summer rainstorm in 2021, a manhole cover at the intersection of West Rock and Whalley Avenue has blown off, and become a spewing, 2-foot-high fountain. Water—mired to an unsettling blackness—roils and sloshes against the side of his porch. The cars that manage to pass flash their emergency blinkers as they squelch through the flood, tires half submerged in the filthy mix of sewage and runoff. Raindrops streak slantwise through the frame. The water is unstoppable; the water is everywhere.

Cavaliere, owner of the antique shop Lyric Hall, has lived through violent floods for the past ten years. He has plenty of footage to show for it—videos of him trekking down the stairs in the middle of the night to find a pool of grayish water at calf-level in the basement, lapping at wooden chair legs and picture frames. Along with the video clips, which he keeps in the hopes of showing the city officials, he’s typed up the measurements of every flood on a sheet of printer paper. “On May 7, 2011 there was 3 feet. On August 15, 2012, there was 4 feet, 2 inches,” he reads. The numbers only grow, tending in the same direction as the sea levels in Long Island sound. “In July 2021, 6 feet, 5 inches. In September 2021, that was almost 7 feet.”

He sets the folded sheet on the wooden end table near the display window. The two of us are standing in Cavaliere’s small, one-story shop; it’s October, 2022. There’s a deep sigh. “[The floods have] taken out the HVAC [Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning] systems, the heating [and] air conditioning systems, so many times I can’t keep up.” Cavaliere, who refurbishes old artwork and repairs gilded picture frames for a living, used to keep his workshop in the basement, until repeated flooding events forced him to relocate to the main floor. His gilt molds and picture frames now lie sprawled across a storefront table. He tries not to think of all the antiques and artworks he’s lost over the years.

Today, the store has no heating. Instead, Cavaliere uses a cast-iron wood stove squatting in the center of the room. He took the furnace out of the basement years ago, fearing that a flood might reach his home’s electrical panels. If any electrical panels got submerged and he accidentally stepped into the water, he explained, “I could get electrocuted.”

Cavaliere and his fellow Westville residents have watched these sewage overflows increase in frequency against a trend of rising sea levels and intensifying storms. They’ve sent dozens of emails to state and local officials, which all go either largely unanswered or forwarded to other representatives. Just last month he sent a sample of floodwater from near the basement stairway to Baron Analytical Laboratories. The results came back the next day, concluding that fecal coliforms in the water “were too high to accurately count.” When the water dries, streets and sidewalks are left with toxic residue and bacteria. “In other words, you know, we could get E. coli, Hepatitis A, typhoid from all these microbes.”

Flooding has upended Cavaliere’s life. “It does something to you all these times,” he said. “It’s traumatic.”

***

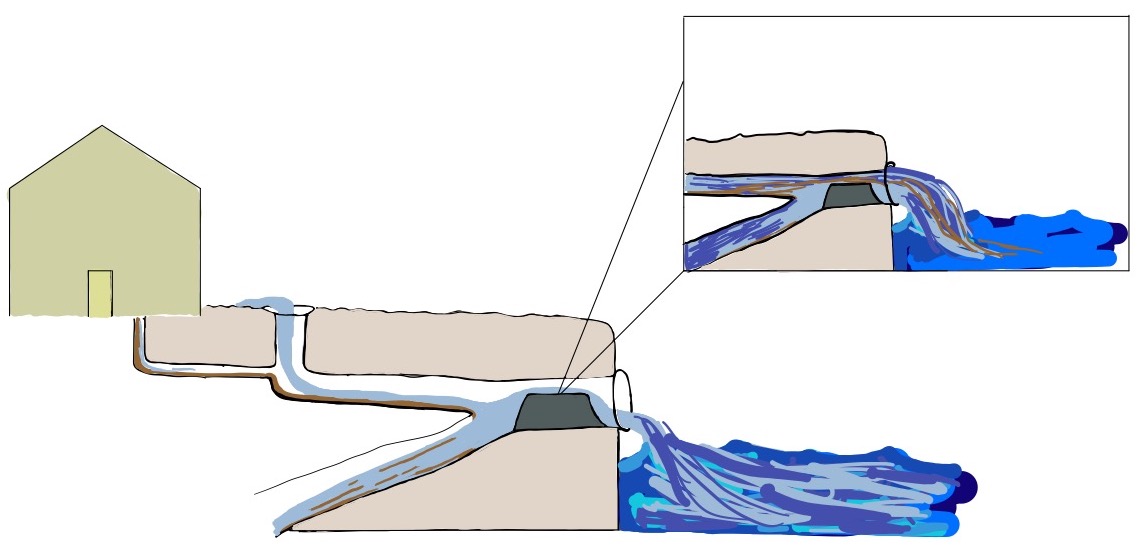

Combined Sewer Overflow (CSO) is common in cities with older wastewater infrastructure, according to Colleen Murphy-Dunning, director of the Urban Resources Initiative (URI). Most infrastructure built throughout the mid-to-late 1800s was designed with a single sewage pipe. Waste from toilets and bathtubs would combine with stormwater runoff and be transported to the processing facilities in East Shore.

The single pipe design quickly retired in the years following the 1970 Clean Water Act, after officials realized that it was causing waste to be directly discharged into the rivers. During heavy rainstorms when the water volume exceeded carrying capacity, the single pipe system would resort to an “outfall”—a safety valve that expelled untreated sewage straight into the rivers. Cities like New Haven had been washing feces directly to the Long Island Sound. Under the Clean Water Act, this wastewater system would be legally required to improve.

At least, it was supposed to be. Despite the intentions of the Clean Water Act, New Haven has been slow to develop its infrastructure. Most of the city’s historic neighborhoods—downtown, Wooster Square, Dixwell, Westville—continue to use the combined sewer system.

There are more immediate consequences to the single pipe system than feces in the rivers. Faced with more sewage than it can handle, enough pressure builds up to pop manhole covers off and send its contents spilling all over the street. “It’s pretty nasty,” Chris Ozyck, URI’s associate director, said as we drove down Front Street in his pickup. He pointed out the townhouse complexes on the slope to our right, where stormwater often rushes down and overwhelms the pipes. As it moves downhill, the sewage-runoff mixture often gets backed up near low-lying areas and floods the streets.

Like most historic urban areas, not all of New Haven’s 555 mile-long sewage system is the same. Most streets constructed farther from downtown now use two pipes—one that specializes in collecting runoff stormwater from the catch-basins, and another that connects to each home’s sewage system. Doing so prevents the sewage flooding from happening.

The situation in Newhallville, a neighborhood in New Haven’s Ward 22, is one such instance of this. Though Ozyck told me that some basements in the neighborhood had been flooding, the culprit seems to be purely runoff for now. Most of Newhallville’s streets have two sewer pipes, which has so far spared its residents the feces-laden horrors. Hunter Irwin, a local resident on Shelton Avenue, moved here for his job at Yale-New Haven Hospital hospital during the beginning of the pandemic and has braved three years of unrelenting storms. He admitted that runoff stormwater can still be a problem—it collects on the curbside and the empty lot across the street, especially during late summer thunderstorms—but so far, it hasn’t been much of a concern.

Graphic by Meg Buzbee.

Dawn Henning, a New Haven city engineer, said that the city has been working steadily to outfit older districts with separate sewer pipes. That’s where URI has stepped in. As part of an effort to divert excess runoff from entering the sewage pipes, the nonprofit applied for grant funding and accepted contracts with the city government to install bioswales—trenches filled with shrubs and vegetation that receive runoff water—in the most flood-vulnerable corners of New Haven. Since 2014, Ozyck and his crew have installed almost four hundred of them across the city.

On a Friday afternoon in October, he and I visited the very first bioswale in New Haven, just outside the Berzelius secret society on Trumbull Street. The rain from the night before collected in tiny puddles by the curbside. The lower leaves of the bioswale’s inkberries and daylilies glistened with water droplets. The soil in the swale felt cool and damp to touch, a sign that the plants in the bioswale had been busy filtering away the runoff. The idea was to return rainwater back into the soil, where it would be taken up by street trees and absorbed into the water table.

“It’s mimicking what nature wants to happen with water, which is that it should go through soils and down and recharge the subsurface groundwater table,” Murphy-Dunning said. In the process, the soil ends up cleaning the water in ways that traditional treatment plants do not. The bioswale’s success on Trumbull exceeded their initial expectations: by naturally filtering the run-off, it managed to save a street that had long suffered from chronic flooding.

***

Climate change has only intensified these sewage overflow events. “The more we experience sea level rise and just…higher and higher levels in the harbor, the more that reduces the capacity of our storm system and…the more we see that flooding,” said Henning.

Global warming’s effects are beginning to be felt in a city that sits right along the water’s edge. “There were a series of storms that happened [in] 2010 through 2015, in addition to hurricanes Sandy and Irene, that were really intense [and] had high return frequencies,” said Henning. During that time, ten- and twenty-five-year storms swept through the city almost yearly. That hasn’t improved: storms that are statistically only supposed to occur once every five to ten years are hitting New Haven annually, explained Henning.

Streets like Quinnipiac Avenue and neighborhoods like Fair Haven have already started eroding. “What used to be a fifty-year storm is now a ten-year storm,” said Ozyck. In other words, a storm with a severity seen only once every fifty years is now occurring in every ten. On Front Street, he showed me homes facing the Quinnipiac River with partial-underground basements that—like Lyric Hall—have experienced a significant uptick in flooding. From the end of Clifton Street, we saw a building partially sinking into the river. The guardrail of the outlook we stood on was just inches away from touching the water itself. Rising sea levels, Ozyck said, has only increased the odds of flooding. Water from the riverbanks will naturally spill onto the streets during an intense rain event, stressing the already aged parts of the city’s sewage system and threatening to make overflows of Westville’s kind dramatically more frequent.

Part of preventing these sewage outpourings will therefore require protecting the city from floods. Single sewer pipes like those in Westville are beginning to overflow with greater regularity as ever-intensifying flood events strain their capacity. Less flooding, then, would mean less overflow. After Hurricane Sandy and Irene hit in 2011, the engineering department received grants from the state and federal government for future flood protection. One of them, the Community Development Block Grant, awarded $4 million to studying green infrastructure development in the Long Wharf area. The research, which Henning was responsible for, explored potential green solutions.

Long Wharf, which is directly beside the Long Island Sound, is currently one of the areas most vulnerable to flooding. The first phase of their proposed FEMA-grant project will expand Long Wharf’s current drainage capacity by constructing a 10-foot diameter pipe from the police station out to the harbor. Another project, led by the Army Corps of Engineers, has plans to build a flood wall along the sea-facing I-95 and install a pump station. In plans to protect the city from sea level rise roughly half a meter higher than the national average by 2050. Combined, the total costs work out to roughly $195.8 million.

The completion dates of both projects remain uncertain. The tunnel proposal is currently under review, which Henning admitted “can take a while.” After the agreement, she expects another six months for permitting and two years of construction. The flood wall awaits two years of design and a three- to four-year construction period.

Bioswales, meanwhile, have provided a faster—and possibly more efficient—short-term solution for the city. “Green infrastructure is much less disruptive to install,” Murphy-Dunning said. One of the greatest challenges to updating the single-sewer system is its cost and labor: adding another pipe calls for digging up the entire road, creating a trench, and connecting the newly-laid pipe to every curbside catch-basin. By collecting runoff on the streets, bioswales help ease the strain on the existing single-pipe sewage system.

Murphy recognized the importance of the city’s current flood-protection projects, but she also brought up the importance of managing its existing impervious surfaces. Man-made materials, such as asphalt, increase the odds of flooding by preventing runoff from entering the ground. And while larger drainage pipes will certainly help, the flooding will only return if the city continues to develop over existing green spaces at the rate it currently is.

Henning tells me that the city itself has no jurisdiction over combined sewage. The engineering department only oversees storm drainage; the sanitary system is managed instead by the greater New Haven Water Pollution Control Authority, a quasi-private entity that has its own long-term control plans. However, Henning did note that “they are under consent order by the [Environmental Protection Agency] to manage the two-year six-hour storm and to have essentially no overflows.”

Photo by Hanwen Zhang.

As it waits for approval on its landmark projects, the city has continued to take steps towards flood resilience. Some of its smaller projects include replacing hundred-year-old clay pipes and cleaning curbside catch-basins.

With grant funding used up, bioswale construction has stopped. Its maintenance remains in the hands of URI. During our meeting Ozyck pulled his truck over to the side of Grove Street, walked out, and tugged out a mat of browning red oak leaves from the bottom. Bioswales have to be constantly monitored and maintained to function properly, he said. Repairing broken guardrails, granite edging, and removing yard-waste is a months-long project for the nonprofit.

“I think we try to work on all scales,” Henning said. She looks forward to running studies using a geographic information system that will help the city capture more data. For areas like Westville’s Whalley Avenue and Forest Road, she noted that “we’re kind of in the study phase of the flooding.” Getting the resources and making sure there is enough to go around will take time. Making sure every neighborhood receives the funding they need, however, is easier said than done. “We get this investment for downtown, but how does it appear in some other part of the city? It’s tough,” she said.

***

On September 6, 2022, New Haven received four inches of rain in six hours—a month’s worth of precipitation packed into the span of a day. Rainwater streamed down streets, bogging cars and school buses. At Yale, Bass Library flooded, Benjamin Franklin’s dining halls seeped water, and the floor of basement butteries grew slick.

That day, in the basement of Lyric Hall, Cavaliere recorded nine inches.

As a densifying urban area, New Haven faces a unique set of challenges. The city has to contend with runoff along concrete surfaces and rising sea levels, bearing the brunt of both inland and coastal flooding. “We’re kind of getting it from all angles,” said Henning.

Back at Lyric Hall, it is mid-October and not quite yet the tail of fall. Sunlight sifts past the balcony, through the windows, onto the refurbished Persian rug at the shop’s entrance, like any other day. The only traces of last month’s flood might be the basement’s faint mustiness as Cavaliere shows me the ball valve he installed. Closing it would shut the pipe that leads to the street sewer main and keep sewage from backing up into the toilet. Now, he explained, the plan is to apply for grant funding that would lift his storefront an additional 2 feet and waterproof the building’s warped foundations.

The back of the house is paint-peeled and sagging. Recently, though, a friend had helped repair the side of the basement. Cavaliere looked out at the pool of golden leaves across the street. Despite all the challenges he has experienced, he’s still hopeful. “It’s a miracle that I’ve managed to survive all this,” he said, still looking. “But I think it’s because I just feel so loved by the community and I love my community, and I am doing exactly what I want to do in my life.”

—Hanwen Zhang is a junior in Benjamin Franklin College.