Author’s Preface: This article is the product of a two-year-long investigation into the presence of admitted Nazi collaborators on the faculty of Yale’s Slavic Languages and Literatures Department in the second half of the 20th century. It relies on dozens of interviews, extensive historiographical research, and thousands of pages of documentary evidence, combed from physical and digital archives including the Rockefeller Archive Center, Yale’s Manuscripts and Archives Library, Yale’s Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University’s Rare Book and Manuscript Library, the Heidelberg University Archive, the Hoover Institution Library and Archives at Stanford University, the CIA’s online FOIA Reading Room, the National Archives and Records Administration’s website archives.gov, the online archive of the Harvard Project on the Soviet Social System, and the online archive of the Novoye Russkoye Slovo accessed through the New York Public Library. Translations of German documents were provided by Charlie Perris, MA candidate in Public History at Freie Universität Berlin.

The first part of the series, published in the September 2021 issue of The New Journal, can be read here.

Prologue

In November 1985, nine years after his past as a Nazi propagandist came to light and his life as a Yale lecturer fell apart, Vladimir Sokolov was still enduring what he called, in letters to the local Russian press, the “torture of waiting.”

He had waited three years for the Department of Justice’s Office of Special Investigations to conclude its investigation of his career with the Nazis and his deception of American immigration officials in the 1950s. He had waited three more years for the trial––which would revoke his U.S. citizenship––to begin. And now, after 11 days of court proceedings, it would still be several more months before Judge Thomas F. Murphy of the Federal District Court for the District of Connecticut rendered a verdict.

As the investigations continued, and Sokolov inveighed in emigre newspapers against the DOJ and the “Devil and his henchmen,” things at Yale returned to normal. The Slavic Languages and Literatures Department filled the position Sokolov had vacated and Russian classes in the basement of the Hall of Graduate Studies resumed as before.

But even after the scandal broke, even after Sokolov retired from Yale early in disgrace and left New Haven for good, and despite a three-year Justice Department effort that compiled depositions of Yale faculty, forensic analyses of German war documents, and interviews with historians of the Holocaust, there was still a former Nazi on the faculty of the Slavic department.

“Had I Come Across You During the War”

Rita Lipson, a now-retired lecturer in Russian at Yale and Dean of Ezra Stiles College from 1982 to 1992, interviewed for Sokolov’s old job in the summer of 1976. She had heard about the opening from Vasily Rudich, then a PhD student in Classics at Yale who later became a professor in the College and a close friend. Through Rudich, Lipson was introduced to Robert Jackson, the acting chairman of the Slavic department, and arranged an interview.

They met in New Haven and talked over lunch, during which Jackson explained that the department urgently needed to find a new Russian instructor. The conversation was pleasant, and Lipson felt that Jackson was someone she could trust. Throughout the interview, however, Jackson was taking care not to divulge too much of what had happened over the year prior. For months, he had been hounded by reporters, asking for more on Sokolov than he was prepared to tell. The pressure had become such that it was difficult for him to talk about the scandal.

All Lipson needed to know was that, because of an emergency, Yale was looking for someone to teach Russian. Lipson had many qualities to recommend her. She spoke the language fluently, had taught at other American colleges, had worked as a broadcaster at Radio Liberty, and had read widely in Russian literature.

Lipson seemed the perfect fit for other reasons. Where her predecessor had been a Nazi propagandist, she was a Jewish Holocaust survivor. As a young girl, in the summer of 1941, she had fled the Polish town of Sarny with her family on one of the last rail transports behind Soviet lines. Within days, the whole area had degenerated into a killing field for the Nazis and local nationalists.

The department hired Lipson soon after that lunch in the summer of 1976. She began teaching three days a week that fall, staying part-time in guest suites in the residential colleges. From the outset, the department was “very accommodating,” she now recalls, but soon it became clear that something was off. She began hearing rumors from other faculty about a scandal in the department from before her time. She wanted to know more, and soon came across the New York Times article from several weeks earlier, dated September 20, announcing Sokolov’s resignation.

“At some point, this article was pointed out to me, and I read the article,” Lipson says. “And lo and behold, I still couldn’t make any sense of it. How does it really apply to me? I just continued applying myself, going to teach my classes. And as time was passing, the environment in the department started to feel a little better.”

In January 1977, now settling into the department and preparing for the start of the spring term, Lipson remembers attending a Russian Christmas party held by the department on the fourth floor of Yale’s Hall of Graduate Studies. The crowd was mainly language instructors and their spouses. Milling around the room was Rurik Dudin, a senior lector in Russian, who had been teaching in the department since 1966, when he was hired as an assistant instructor, and would continue there until his retirement in 1989, six years before his death. Dudin, Lipson recalls, had been drinking heavily throughout the night. Late in the evening, he strolled over to Lipson, she says, and tilted her chin up with his pointer finger. He looked her in the eyes, she recalls, and told her: “‘You pretty Jewess, had I come across you during the war…’” Trailing off, Dudin formed his hand into the shape of a pistol, Lipson remembers, pointing it at her forehead, and he mimed the imaginary gun recoiling, mimicking the sound of the blast with his voice.

By then, Lipson had become close with Robert Jackson, no longer the Slavic department chairman, and with Edward Stankiewicz, a professor in the department and also a Holocaust survivor. Lipson went to Jackson and Stankiewicz soon after the encounter with Dudin, and told them what he had said and mimed.

They weren’t surprised, Lipson recalls, but they told her that nothing could be done and that to keep her job at Yale, it would be best not to make a fuss. It was an open secret in the department, kept close enough to the vest to avoid a second Sokolov-like scandal, that Dudin’s war experience was fraught. At the time, Stankiewicz, according to Vasily Rudich, had claimed to have heard Dudin boasting that he had served in the Waffen-SS and had executed Jews in firing squads. Jackson, when I spoke with him in the summer of 2021, nine months prior to his death at the age of 98, had said that Dudin had told him something similar to what Lipson said she had heard at the Christmas party.

“He drank to a degree,” Jackson said, “and in front of the Hall of Graduate Studies one time, he said to me [looking out at the students passing by], ‘Jackson, if we were in Russia, I could go er er er er er,’ indicating a machine gun.”

Even among the students, rumors circulated that Dudin had fought in some capacity with the Nazis during the Second World War. “Someone told me that he had been in this Vlasov unit that defected to Hitler,” says John-Paul DeRosa ’77, a former student of both Sokolov’s and Dudin’s. “And he [Dudin] was literally a teenager […] and that he had, at the end of the war, when the Russians were coming, hidden in a haystack and barely escaped pitchforks and things, and hid out and probably changed his identity or whatever to get out, away from being killed by the Russians.”

In many ways, Dudin, whom DeRosa remembers being “built like a bull,” embraced the persona of the anti-Soviet warrior, the “rustic Cossack,” as another former student John Zucker ’76 would put it in his remarks at the 1996 memorial service for Konstantin Hramov, another lecturer in the department. In a summer course Dudin co-taught with Sokolov in 1975, DeRosa recalls Sokolov’s literature lessons ending halfway through the class and Dudin getting up to take over and teach history. Often, DeRosa says, Sokolov would play-act getting caught in the sights of Dudin’s machine gun and scurry away from the blackboard, “with a grin […] he [Sokolov] seemed to think this was hilarious.” In 1975, the war was thirty years behind them. Now they could laugh about it.

All in the Family

In the fall of 1940, Rurik Dudin enrolled at the University of Kiev. It was a year before the Nazis pierced through miles of Ukrainian forest outside Kiev, encircled and captured the city, and began a two-year campaign of starvation and slaughter there.

In his adolescence, the war and the Nazis’ final solution were all around Dudin. For years, he had been educated at a Russian preparatory school in the majority-Jewish city of Będzin, Poland. He left the area, he would later write, in the “autumn of 1939,” at age 15, around the time when the city fell to the Nazis. In September of that year, the Nazis would enter the city and set fire to its central synagogue, burning the surrounding rows of houses to the ground and dozens of Jews to death. Over the next three years, the Nazis would concentrate tens of thousands of the city’s Jews into a ghetto, deporting nearly all they hadn’t shot on sight to forced-labor and death camps.

After he left Będzin, Dudin would write, he returned to his parents’ home in the Upper Silesian region of Nazi-occupied Poland. The family, it seems, was well-off. His father Vladimir, according to a declassified document in the CIA file of the high-ranking Nazi and post-war agency asset Gerhard von Mende, which I accessed through the agency’s online FOIA library, had graduated from the Corps of Cadets of the Imperial Military Academy. He later served as an officer in the Imperial Guard, before leaving “for the purpose of developing his estates in the vicinity of BRIANSK,” the document reads. Vladimir Dudin, because of his “anti-Soviet attitude,” according to the file, had his oldest son Leo, who was 14 years his half-brother Rurik’s senior, educated by private tutors before he entered the University of Kiev in 1929.

Rurik Dudin left home for Kiev to finish his secondary studies at a gymnasium in the spring of 1940, before enrolling in the Philosophy Department at the University of Kiev, where his brother Leo had recently been appointed Director of the Department of Foreign Languages. At the university, Rurik would later write, he studied for two semesters “with the career goal of becoming an historian, focusing on Russian and German history.” A different future was in store for him.

By mid-September 1941, the Nazis had choked off all ways in and out of Kiev. Over ten days, the Soviet regiments within the city fought to break through the circle of German Panzer groups, to no avail. As the city fell, the streets emptied and the University shuttered its doors. On the sidelines, the Dudin brothers waited and watched.

“Because my brother and I and the Soviet regime did not see eye to eye,” Rurik would later write in his application to enroll in Heidelberg University in 1949, which I obtained directly from the university’s archive, “we remained in Kiev under great danger, awaiting the approaching German troops.”

In October 1941, several weeks after the Nazis had taken the city, Leo Dudin found work in a “translation agency,” according to a Nazi intelligence interrogation protocol dated December 18, 1941––which was reviewed by Igor Petrov, an independent researcher based in Munich, and re-translated from Petrov’s Russian for my use by Benjamin Tromly, a professor of history at the University of Puget Sound.

(The document, according to Petrov, was published in “Soviet propaganda literature during the Cold War,” which, he says, he rarely cites because of problems with authentication; “but in this case,” he says, “since there is no better source yet and there are some indirect confirmations of the authenticity of the documents, I make an exception.” The documents revealing Sokolov’s past as a Nazi propagandist had also first appeared in the Cold War Soviet press, before the DOJ forensically authenticated them and Sokolov, under oath, admitted to being their author.)

Leo Dudin had been brought in for interrogation by the Nazi authorities, the document suggests, about three of his acquaintances in the city––local writers recruited to staff the Nazi-run newspaper, Ukraïnske slovo (“The Ukrainian Word”). He had met the writers, he would recall in his memoirs, in a lavish office at the paper’s headquarters. The walls, he would write, were paneled with birch wood and vases of flowers filled the room. Above the editor’s table hung portraits of Hitler and Symon Petliura, the president, from 1918 and 1921, of a short-lived independent Ukrainian republic.

The Nazis had become worried about the political direction of Ukraïnske slovo’s editors, according to the document. They believed the paper was drifting toward Ukrainian nationalism, away from the German line. The Nazi authorities wanted Dudin to confirm what they feared was brewing. Leo, the document reads, told his interrogators: “Based on my loyal attitude towards Germany, Mr. Rogach [the paper’s editor-in-chief] asked if I was a Ukrainian or a slave to Germany. To this, I answered him that for the time being we needed to fight together with Germany against her enemies, and the question of a free Ukraine was not yet ripe.”

In February 1942, the Nazis executed Rogach and left his corpse in the Babi Yar ravine, where six months earlier they had massacred 33,771 Jews. Soon after, Leo became editor-in-chief of another of occupied Kiev’s Nazi-run dailies, Poslednie novosti (“The Latest News”). Meanwhile, Rurik enrolled in the Kiev Conservatory of Music’s “Theater Criticism Department,” he would later recount, the only university program there that would restart under the occupation as part of the Nazis’ cultural policy for the region.

But the lives that the Dudin brothers built in Nazi-occupied Kiev would not last. The Soviets retook the city in the winter of 1943, routing the Nazi Panzer units stationed there and pushing them south along the Dnieper River.

“As German troops surrendered Kiev,” Rurik Dudin would later write in his Heidelberg University application, “my brother and I decided to join the German retreat, and I enlisted in the Wehrmacht, to which I belonged until the end of the war. I was distinguished multiple times, and served last with the 5th Mounted Regiment, 4th Cavalry Division. I decided to get actively involved in the war because I am a staunch anti-Bolshevik, and I’ve felt their scars upon my own body.”

Leo, it seems, left Kiev for Berlin before the Nazis’ final withdrawal from the city in the fall of 1943. After proving his reliability, the Nazis had sent him, according to the biographical blurb of his memoir and documents in the CIA file of Gerhard von Mende, to Berlin to work in the Vineta, the anti-Soviet unit of the German propaganda ministry.

Because of the paucity of surviving war documents from the Wehrmacht, Rurik’s path out of Kiev is less clear. But serving in the equestrian units of the Nazis’ 4th Cavalry Division through the close of the war would likely have placed him in Hungary at the Nazis’ last failed attempt to salvage their eastern campaign in the spring of 1945. In a 1980 essay for the Russian political quarterly Kontinent, Rurik would also mention his tours with the Nazi Cossack units, who, according to the historian Jozo Tomasevich, “quickly established a reputation for undisciplined and ruthless behavior.”

The Nazis deployed those units, beginning in the fall of 1943, in Yugoslavia. There, Tomasevich writes, on horseback, armed with German machine guns, they raided and torched villages throughout the region, indiscriminately killing and raping civilians and hanging the corpses of anti-fascist partisans from telephone poles along the railroad. Publicly, Dudin would never write in detail about his self-confessed service in the Nazi Cossack units, or whether it implicated him in the bloodletting of the Yugoslavian countryside. Still, it was a distinction he was claiming for himself in the emigre press until at least 1980 and whispering in the ears of his colleagues in the Slavic department.

Big Brother

When the war was over, Rurik Dudin made his way to Allied-Occupied Germany, where his brother and parents had already settled. Over the next four years, while evading repatriation to the Soviet Union, he would later say, he worked as a journalist for the Western services, putting his knowledge of German, French, Russian, and Ukrainian to use, and paying his parents’ bills.

Laying low in the years after the war in small villages in the south, Rurik took the German name “Hans” and stayed close to the ring of Russian expats he had met while serving the Nazis. Rostislav Antonov, a former captain in the Nazi-aligned “Russian Liberation Army” and assistant to Andrei Vlasov, the army’s leader, was one of them. After the fall of the Reich, Antonov was tried and acquitted in 1945 on charges of being a “White Russian Nazi,” sold alcohol and apples on the black market, and came to be hired by American intelligence to do reconnaissance on the East German border. Michael Schatoff, who had also served the Nazis and been made one of Vlasov’s bodyguards, was another of Rurik’s contacts.

Leo Dudin, meanwhile, was moving in similar circles and gaining influence in high-up places. In the early years of the Cold War, he had caught the attention of U.S. intelligence officers stationed in Germany. Judging by declassified army intelligence files from the period, they seem to have valued his connections to the administrative underbelly of the collapsed Reich, especially his associations with former Nazi propagandists then living in obscurity between Munich and Berlin. In his dealings with the Americans, Dudin advertised these contacts as a potential gold mine of personnel for the new anti-communist effort.

“Dr. Dudin feels personally,” reads one declassified U.S. army intelligence memo dated April 23, 1947, sent by Colonel Henry C. Newton to Carl F. Fritzsche, the Assistant Deputy Director of Intelligence for the Army’s European Command, “that the idea of working with the former leading officials of the German Propaganda Ministry can be most helpful, inasmuch as the individuals named have excellent sources of information and are thoroughly qualified for work of this nature.”

The Nazi propagandists in Leo Dudin’s circle were already seasoned communicators of anti-Soviet ideas and, he believed, would be useful in the emerging confrontation with Russia. During the war, many had ascended into the high ranks of the Reich. Among Leo Dudin’s Nazi contacts courted by American intelligence were Eberhard Taubert, “one of the valued assistants of Dr. [Joseph] Goebbels,” and Gerhard von Mende, who, according to the same memo, “was supposed to be the chief advisor on the Soviet question for the German government.”

Leo Dudin had been inside the Nazi edifice as it came crashing to the ground. He had already seen the Nazis fail to defeat the Soviets once, failing for reasons he believed had been strategic and avoidable, and he hadn’t forgotten them. Now in his talks with the Americans, he cautioned them against giving the former German propagandists too much latitude. As agents in the new conflict, they would have to be kept from repeating their “serious errors in judgment in shaping policy” during the Second World War. Russians who had served the Nazis, like himself, Dudin told them, possessed “more intimate knowledge of the problem” and were better suited to the long task ahead.

The Americans told Dudin that they were well aware of the risks borne in engaging his and other Nazi contacts and would handle them accordingly. “We are planning our policy toward the Soviet not for ten or twenty years,” Newton said they had assured Leo, “but for a hundred years.” As for seeking out Russian collaborators with the Nazis, Leo Dudin had them convinced. “Dr. Dudin speaks excellent English and is extremely well educated,” Newton wrote to Fritzsche. “I am convinced that he would be of considerable assistance to you and suggest that some contact be made.” It was the beginning of a longer partnership.

In the summer of 1948, before the Harvard sociologist Talcott Parsons flew to Germany on a mission to find and hire Russian expats in the country for the university’s Russian Research Center, according to the historian Jon Wiener, he had, through an army intelligence officer, planned to meet with Leo Dudin in Munich. After seeing Leo, he would write to Clyde Kluckhohn, the head of the Research Center, saying that he had met with two other Russian expats, members of what he called the “Dudin Group,” and, according to Wiener, “two U.S. Army intelligence officers who employed them.”

After talking with Dudin and his set, Parsons started to feel uneasy about bringing them to Harvard to write dossiers on the USSR under the university’s auspices. They had once been Nazis, after all. “Perhaps I was a little too hasty in my recommendations on the Dudin group,” he wrote to Kluckhohn in June 1948. But there was something alluring about them still. “Their political inclinations may be extreme––and yet––I want to go back to them with the wider perspective.”

A year later, in the summer of 1949, another professor from Harvard’s Russian Research Center did just that. Over the course of several months, the political scientist Merle Fainsod traveled throughout West Germany, interviewing the Center’s contacts there for the “Harvard Project on the Soviet Social System.” On June 14, 1949, he sat down with Leo Dudin in Munich. They spoke throughout the day in English and Russian, and Fainsod recorded Dudin’s life story as he told it.

Dudin’s father, Fainsod learned, had been a major landowner before the 1917 revolution, hid his past when the Bolsheviks came to power, and homeschooled Leo from middle school on “to insulate him from the influence of the new regime.” When he was old enough, Leo applied to the technical institute in Kiev, where the family was living at the time, hoping to become an engineer.

The institute rejected him and soon after, in 1929, he applied to the Ukrainian Institute of Linguistic Education, a part of the University of Kiev, where, like other children of the “old intelligentsia,” he studied German and English and trained to become a translator. Five years later, after he had completed his schooling, he became a foreign language instructor for Russian troops in the Far Eastern Military District, building roads near the Chinese border, and worked as the private tutor of generals supervising the army presence there.

In 1936, by then finished with his stint with the army and back in Kiev, Leo was hired to the faculty of the Kiev Industrial Institute, doing mostly administrative work, which he resented. After three years of “endless annoyance,” shuffling around schedules and determining room assignments, he was invited by the Rector of the University of Kiev, who had taught him in the languages department close to a decade earlier, to become Chair of Foreign Languages at the university. He took the job, working there until the Nazis descended on the city in 1941.

When the invasion began, Leo was told he had two options: evacuate with the university or enlist as an “interpreter-translator” with the army, ranking as a captain. “He told the University that he was joining the army, the army representative that he was evacuating with the University,” Fainsod would write in his report on the meeting. “Instead, he went into hiding to await the coming of the Germans.” Laying low in the shadows of Kiev, as its streets emptied, its buildings crumbled, and its people fled, Leo Dudin was hopeful. Before the occupation, the city had been home to 900,000 people. By the spring of 1942, only 350,000 remained. According to an interview with an unidentified former colleague of Leo’s at the Nazi newspaper he edited, also conducted by the Harvard Research Center, “five or six professors out of 500” were still in the city after the occupation. Leo Dudinwas one of them. “After the Germans arrived,” Fainsod’s report continued, “he says, he was bitterly disappointed by their behavior, but nevertheless served them as editor of a Kiev newspaper under the occupation. When the job got him into trouble, he found another position in Berlin.”

Whatever misgivings he might have had about Nazi rule, the trouble Leo Dudin had found in Kiev, it seems, had not been with his Nazi supervisors, but with Ukrainian nationalists in the city. In a letter apparently sent from the Nazi command in Kiev to the Reich Security Main Office in Berlin, reviewed by Igor Petrov and translated into English for my use by Benjamin Tromly, Leo was said to have advocated the “unconditional recognition of German domination over Ukraine, as he holds the opinion that Ukraine is not capable of independent political life. He has proven his political beliefs more than once, and local chauvinists threaten him with revenge and death.”

In the end, the Nazis may or may not have “disappointed” Leo Dudin, but he never disappointed them.

Whether it was cunning, conviction, or some combination of both that had led him to join the Nazis, Leo Dudin’s services to the Reich had made his new life in Germany possible. In the span of 10 years, he had gone from tutoring Red Army generals in English and German and working in Goebbels’ office to narrating his life story to Harvard professors and consulting on Cold War strategy for American intelligence officers. Now that he was firmly established, he was prepared to bring his younger brother Rurik along.

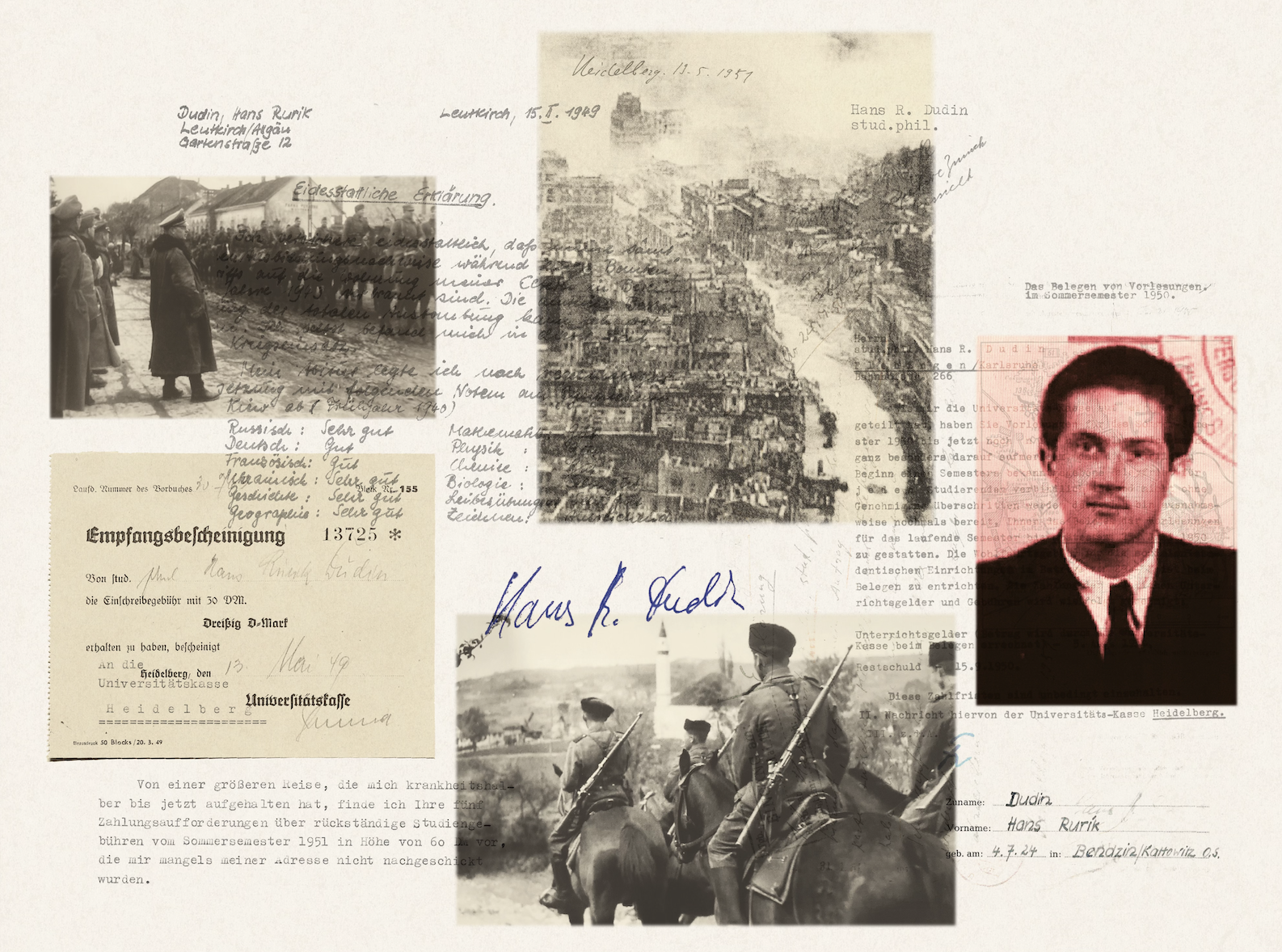

In January 1949, Rurik applied to Heidelberg University. As far as his qualifications were concerned, there was little for the university’s administration to rely on except his word, he would write in a sworn statement prior to his admission, since all his academic papers had been lost during the war. “I affirm under oath that the entirety of my educational certificates were burned in my parents’ home in Berlin during a bomb attack in the year 1943,” he would write. Without those documents, Rurik’s word alone likely would not have been enough for the university to go by. But Heidelberg also had sworn attestations that the documents had once existed and been destroyed from Leo Dudin; Michael Schatoff, Rurik’s friend from the Nazis’ Russian units; and the Kiev-born painter Sergei Bongart, who, by then, was living in Memphis, Tennessee.

Heidelberg University admitted Rurik to its philosophy program that year, and he enrolled in May. By the summer of 1951, he was still enrolled at the university but hadn’t attended a single lecture for the entire term or paid his tuition. The university’s bursar sent him five payment requests for the term, which he said, in a letter dated November 7, 1951, he had missed due to “a major trip, which held me up until now due to illness.”

“I’m sorry to have to tell you that,” Rurik continued, “as a result of my condition after traveling, I won’t be able to come speak to you in person, nor will I be able to pay my debt within the near future.” The bursar’s office wrote back to Rurik later that month telling him that he had been stricken from the university’s directory for the summer term, losing the credits he should have accumulated over those months.

Then on May 30, 1952, the bursar wrote to Rurik again to inform him that he had been expelled. Not only had he skipped the entire summer term, failed to pay his dues, missed the re-registration window for the 1952-3 academic year, and been officially removed from the university, he hadn’t attended a single class in the winter of 1951, despite being enrolled.

On December 12, 1951, when he should have been in class at Heidelberg University, Rurik Dudin was on the USNS General M.L. Hershey, setting sail for New York.

Brave New World

Two weeks later, on December 26, 1951, Rurik Dudin arrived in New York. Like thousands of other Russian-speaking emigrés, he got himself settled in the new country through the Tolstoy Foundation, a relief agency set up in the spring of 1939 in Valley Cottage, New York, 30 miles north of Manhattan. The Countess Alexandra Tolstoy, Leo Tolstoy’s youngest daughter and a leader in Russian America circles throughout the first half of the 20th century, created the foundation to receive “displaced persons” from Eastern Europe and to help them acclimate to America, especially by connecting them to jobs and housing.

Like Rurik, most arrivals at the foundation had come to America by way of Germany as part of the “second wave” of Russian emigrés to the U.S. Many had been Red Army soldiers, civilians captured and forced to work in slave labor camps by the Nazis, or collaborators with the Nazis who had taken up residence in West Germany after the war. In the paranoid early years of the Cold War, in the eyes of American officials, a proven commitment to fighting the Soviets, even if it had been with the Nazis, was a reason to expedite, not slow, the immigration process. Receiving “escapees or defectors from behind the Iron Curtain,” the Countess Tolstoy believed, would prove to be an “important factor in psychological warfare,” effective at weakening the Soviet government’s control over the Russian-speaking world.

Leo Dudin had made it to America months before Rurik, on September 7, 1951, and, after being received by the Tolstoy Foundation himself, he had stayed with the actor and radio announcer Sergei Dubrovsky in Brooklyn before moving to Queens. In America, Leo already had cultivated a reputation as an authority on Russia, and soon began contributing to the Novoe Russkoe Slovo (“The New Russian Word”), a major emigré paper in New York, writing under the pen name Nikolai Gradoboev. He stayed on as a member of the Munich-based Institute for the Study of the USSR, a CIA-backed research center that, from 1951 to 1971, hosted academic symposia and produced reports on Soviet affairs. He also became a script writer and broadcaster for Radio Liberty, the station formed in 1951 out of the American Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia, a sister organization of the Institute, also funded by the CIA. He was putting the connections he had spent years solidifying in Germany to good use.

When Rurik arrived in the States, he stayed with Leo at his home. Within months he had found work that promised him access to influential American actors in the Cold War and gave him cache in emigré politics. No later than April 1952, only four months after he had first traveled to America, Rurik became the president of an organization called the Free Russian Youth Club in America. The Free Russian Youth Club had been founded in New York three years earlier, according to a September 15, 1951, article in the New York Times, “to serve the cultural needs of the newcomers and as a vital link between Russian and American young persons.” But it wouldn’t be until the fall of 1951 that the club had sufficient funds to open its own headquarters, a three-story brick building at 144 Bleecker Street in Greenwich village, at the same address where the America Free World Association, an anti-fascist activist group, had its offices during the Second World War.

The Tolstoy Foundation and the International Refugee Organization (a precursor to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees) supported the club in part, but most of the financing came from the Ford Foundation’s Free Russia Fund. Beginning in April 1951, the Ford Foundation had put aside a massive pot of money in the fund, led by George Kennan, an early architect of America’s Cold War foreign policy, to sow homegrown institutions dedicated to advancing American interests and bringing Russian exiles into the cause.

In an internal Free Russia Fund memo, dated July 18, 1951, which I reviewed alongside other documents at the Rockefeller Archive Center in Sleepy Hollow, NY, the fund’s then-director George Fischer described its goals as being seven-fold. In order, they were: the “humanitarian” rescue of refugees from the USSR; the “coddling” of Soviet exiles by encouraging their “intellectuals [sic] and professional activities;” generating “knowledge of the USSR;” demonstrating the “good faith” of America; strengthening America’s anti-Soviet strategy; deterring total war; and “the reshaping of totalitarian man.”

In the winter of 1951, the Fund was renamed the Eastern European Fund, signaling its broadened purview as a catch-all source of grants for organizations targeted toward new arrivals from Russia and Soviet satellite states. The Ford Foundation was making a major investment with the fund. In its first five years of operation, the foundation funneled $3,791,500, equivalent in today’s dollars to $41,498,943.25, through the Eastern European Fund, into dozens of projects.

More than a dozen “community integration programs” around the country, like the International Institute of Boston, the Welfare Council of Metropolitan Chicago, and the New York Association for New Americans, were under the Eastern European Fund umbrella. Resettlement agencies, like the Tolstoy Foundation and the United Ukrainian Relief Committee, received funding, too. The Fund also supported “cultural” projects, like the literary and political magazine Novy Zhurnal (“The New Review”) and the Chekhov Publishing House, which printed English translations of Russian authors and translated American classics, like Willa Cather’s My Ántonia and John Truslow Adams’ The Epic of America, into Russian.

Then there was the Free Russian Youth Club in New York, where Rurik Dudin took over in the spring of 1952. In its first year and a half up and running out of its premises on Bleecker Street, between May 11, 1951, and December 15, 1952, the club received $36,970, the equivalent today of $409,158.95, from the Eastern European Fund. With all this cash, the Fund expected the club, according to a summary of disbursed grants dated October 31, 1953, to be “furnishing Russian youth with a fuller knowledge of American democratic principles and traditions and other phases of American life by helping maintain a meeting place where activities conducive to this may be carried on.”

Members of the Fund were encouraged by what they initially saw at the club. By the spring of 1952, a couple hundred students passed through each week, taking English lessons, playing chess, volleyball, ping pong, and musical instruments, fencing, dancing, and attending lectures on American and Russian politics. The club started up a choir, stamp-collecting and photography groups, a theater troupe, and literary and politics discussion circles. Rurik Dudin himself trained a “sniper’s team” of 14 students at the club, taking them on occasional trips out to the countryside to shoot .22 rifles, in preparation for competitions with other youth squads in the area. “The youth feels that the FRYC [Free Russian Youth Club] is its baby,” read a May 27, 1952 report to the Eastern European Fund from the club’s governing committee. “There are many examples in the last time showing that the Club is considered the only cultural center of the youth.”

On the evening of September 17, 1952, Donald Lowrie, at the time the assistant director of the Eastern European Fund, stopped by the club to see these activities with his own eyes. “I had introduced myself as a chance visitor,” he would write a day later to Melvin Ruggles, then-director of the fund, “and the Club members had no idea of my connection with the Eastern European Fund.” The club’s vice president gave Lowrie a tour of the premises. About forty kids were in the hall that night, some playing chess, others playing sports. The building was well-kept and had a “wholesome, comradely atmosphere,” Lowrie wrote in the letter. Despite the good feeling in the room, the club was facing serious financial pressure, Lowrie was told, and it was unclear how long the organization could survive.

The day after he stopped in at the clubhouse, Lowrie wrote to Rurik Dudin to tell him about his visit and to congratulate him on his success with the FRYC. He wanted to help Dudin plan the club’s future. “I would very much like to meet with you and discuss your organization, and would appreciate it if you could come to this office [the Eastern European Fund’s office in Midtown Manhattan] some time at your convenience.”

The next week, on September 24, 1952, Dudin and Lowrie got together to discuss the club’s budget and goals. FRYC had plans to create competitive chess, fencing, and soccer teams, a ballet studio, and three new series of lectures, geared toward easing the process of integration, the first on “American life,” the second on “general cultural topics, Russian and American,” and the third, of particular interest to Lowrie and the Eastern European Fund, on the “USSR today.”

“Dudin points out,” Lowrie would write about the third series of lectures in an internal memo dated September 26, 1952, “that many of their members entering the Armed Forces are expected to be of particular use as persons informed about life in the Soviet Union and correlated topics […] These men could be made much more useful and probably improve their position in the Armed Forces as a result of their attendance at such a course of lectures.”

A week later, Dudin returned to the Eastern European Fund’s office with a more substantive proposal for the third series of lectures he had discussed with Lowrie. On October 2, 1952, he delivered to the Eastern European Fund office a three-page report on a “leadership training program” he hoped to institute at the Free Russian Youth Club. He conceived of it as a 48-week initiative taking place every Saturday morning through Sunday evening, during which a select group of 15 to 20 youth in the club would be primed on the “Soviet army, the Soviet economics, the situation in the party machine, Soviet life, and maybe, some other subjects.” The course, Dudin wrote, would be taught in part by his contacts in New York, who had come over from Germany after the Second World War. It would, he suggested, prepare its students for “all kinds of intelligence and counter-intelligence offices” in the American military.

From May 1951 to July 1952, the Eastern European Fund had awarded the Free Russian Youth Club $20,000 in four installments of $5,000 grants. But by late October 1952, as Dudin pitched enticing plans for boosting America’s prospects in the Cold War to higher-ups at the fund, the club had practically no money on hand. By late November, things had only deteriorated. The club couldn’t pay salaries, electric bills, or rent, and had fallen into thousands of dollars in debt. “There is a real crisis in the situation of the Free Russian Youth Club,” the club’s then-director Blair Taylor would write in a November 26, 1952 letter to Ann Walton, at the time the Eastern European Fund’s executive secretary. Per Taylor’s request, the Fund agreed to infuse the FRYC with a $3,000 emergency grant on December 1, 1952 to pay down what it owed and to get through the end of the year.

A couple of days later, on December 3, 1952, after the Eastern European Fund had agreed to bail out Dudin’s club, Lowrie sent him a letter, hoping to clarify the fund’s relationship with the FRYC as it reeled the organization in from its sea of debt. “In the light of certain recent conversations,” he wrote, “I think it might be useful if we state in writing, the purpose and hopes of the Eastern European Fund insofar as they concern your organization.” The fund, he told Dudin, was a “non-political” organization, and couldn’t overtly support whatever his broader ideological ambitions for the club were. The club could only receive funding for activities related to its mission to integrate Russian youth into American life.

Before Lowrie’s note arrived, Dudin, as president of the Free Russian Youth Club, had become increasingly involved in emigré anti-communist politics in New York. At a November 9, 1952, rally held by a phalanx of emigré anti-communist organizations in America, explicitly political ones, many with roots stretching back to Nazi Germany, he had been named in the newspaper Novoe Russkoe Slovo (“The New Russian Word”) as one of roughly a dozen leading representatives, out of a crowd of 800 or more attendees––the voice of the “Russian youth.”

This sort of activism did not align with the Eastern European Fund’s general aims and nonprofit bylaws. From its inception, the Fund had been surveying and hoping to indirectly shape the political landscape, “‘priming the pump’ for activities which will later carry under their own momentum,” according to its operating principles. Dudin’s club, in order to secure future support from the fund, would have to abide by those rules.

In December 1952, after the emergency grant came in, money continued to flow from the Eastern European Fund into the Free Russian Youth Club, with Dudin still serving as the club’s president. The Fund had agreed, at a meeting of its board of trustees on December 15, 1952, to disburse a $13,970 grant to the club, giving it a sizable runway for the coming year to continue its programing and coordinate joint efforts with other emigré youth groups in New York.

Eight months later, Dudin, though still a senior officer of the club, was no longer its president, having swapped roles with Blair Taylor, the former FRYC director. By August 1953, the thousands of dollars sent by the Fund had been exhausted again, and the club was in the midst of another crisis. It had raised no additional money that year to offset its expenses and could not account for how it had spent that year’s grant money, sparking the Fund to pause new financing and hire a team of independent auditors to get an accurate picture of FRYC’s books. The club had been evicted from its location on Bleecker Street, and agreed, through an attorney, to pay $1,250 in back rent and vacate the building. They had gone back to the Eastern European Fund, pleading for cash to pay down the debt, which they received in September, but failed to pay the $200 they owed their attorney, who, becoming “thoroughly disgusted and angered,” sought the money directly from the Fund. They then moved the club’s operations from Bleecker Street into a house on East 18th said to be owned by a Russian prince, where, they assured members of the Fund, their operating expenses would be trimmed to zero.

On November 4, 1953, Ann Walton, then the executive secretary of the Eastern European Fund, went to the new headquarters of the club to meet with Blair Taylor and to determine whether anything could still be salvaged from the relationship. When she arrived at the East 18th Street address, Walton would remark in an internal memo dated November 5, 1953, she could see that the house was “indeed a possible place for a variety of group activities.” But the place looked like it had been abandoned. The windows were shuttered and coated in grime. No light hung over the front door or in the foyer, and rotting garbage and dirty clothing were piled up inside. “A good deal of demoralization in the group is evidenced further by notice from the telephone company that unless the bill of $49 is paid promptly, service will be discontinued,” Walton continued.

The administrative problems that had plagued the Free Russian Youth Club for close to two years were starting anew, but this time it was nearly the end. The organization’s leaders had treated the club as a means to an end, a nice-sounding platform that promised good connections and real authority but on its own had limited reach. They had tried to develop the club as part of their larger ideological goals, selling it to their benefactors as a crucial element of Cold War operations. But as the Eastern European Fund began sunsetting its support in the winter of 1953, whatever little will had been left to continue the program among the club’s officers was gone. Rurik Dudin had been in charge of the club for close to two years, and, watching it cave in all around, Walton would write in the same memo, he was “eager to be relieved of his duties.” So he left.

The Path to Power

Now it was Rurik Dudin’s chance to break into the political arena of New York emigré anti-communism. He became involved in the North American Department of the Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (SBONR), where his friend Michael Schatoff––who, like himself, had been in the Nazis’ Russian detachments, and whom he had listed as a reference on his application to Heidelberg University––was chairman. The SBONR was one of about a dozen emigé anticommunist groups active in America in the 1950s, all organizing under similarly tongue-twisting names. Besides the Union of Struggle for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia, there was the Union of Liberation Movement Soldiers, the Union of Struggle for the Freedom of Russia, the Russian People’s Movement, the Vlasov Association, the Russian Anti-Communist Union of Non-Party People, the Association of Ukrainian Federalists, and the National Alliance of Russian Solidarists (NTS).

Most of the groups had emerged from the same place––Nazi Germany––with like-minded goals. They hoped that by building the infrastructure for aggressive anti-communist advocacy on behalf of Russian-speaking emigrés in America, they would be able to make new inroads with intelligence agencies, lobby U.S. policymakers to adopt a more militant Cold War strategy, and form a kind of Russian government in exile.

To a degree, they succeeded. In the fall of 1952, the disparate groups managed to coalesce under the banner of the Coordinating Center of Anti-Bolshevik Struggle (KTsAB), a project funded by the CIA through its subsidiary, the American Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (AMCOMLIB). The Coordinating Center, according to an English translation of its governing principles included in a declassified State Department memo sent by the American diplomat Charles W. Thayer on November 25, 1952, was committed to the “active struggle directed toward the liquidation of the anti-peoples communist dictatorship […] and toward the establishment on this territory of a democratic regime.”

Through his post at the SBONR, Rurik Dudin became an officer of the Coordinating Center, working closely with his future Yale colleague, Vladimir Sokolov, then the chairman of the North American branch of the right-wing nationalist National Alliance of Russian Solidarists (NTS). Before they both arrived at the Coordinating Center, the two had been working in the Eastern European Fund network at the same time, Dudin heading the Free Russian Youth Club and Sokolov editing manuscripts at the Chekhov Publishing House. All the while, they were delivering speeches at the same rallies.

Now, according to a February 20, 1954 article in the Novoe Russkoe Slovo, Dudin and Sokolov were together again in New York, in the same room, as representatives of the Coordinating Center, negotiating with officers from the Russian Political Committee, another New York anti-communist organization, on the matter of how best to plan “their activities in relation to the official institutions of the United States and on joint work to explain the ‘Russian question’ to the American public.”

Dudin and Sokolov had grandiose ideas about their place at the Coordinating Center, considering it to be their opportunity to “appeal […] to the conscience of the world.” A couple of months after their backroom negotiations in the New York circles, they seized it. Writing as leaders of the Coordinating Center, Dudin and Sokolov would publicly lobby John Foster Dulles, the U.S. Secretary of State, in an open letter dated April 22, 1954, available in the Congressional Record, to investigate the alleged kidnapping of an anti-communist activist in West Germany by Soviet agents.

But the Coordinating Center, with all its government backing and ambitious plans to win hearts and minds, would ultimately be short-lived, splintering only months after it had been formed due to in-fighting among its component groups. In the aftermath, Dudin went back to concentrating his energy on the SBONR and Sokolov did the same at the NTS, still hoping to advance the Russian nationalist movement in America and to stay relevant in the eyes of Cold War policymakers.

Even after the Coordinating Center had disintegrated, Dudin and Sokolov stayed in touch with one another and kept the same company in New York. In the spring of 1955, still as a member of the SBONR, Dudin would attend the opening night of Sokolov’s NTS clubhouse in Brooklyn. In subsequent years, they would give lectures at the same events on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, and sign the same open letters in the pages of the Novoe Russkoe Slovo, where, eventually, they would both become regular authors.

In the late 1950s, after years of striving for influence, forming political alliances and watching them burn, both Dudin and Sokolov’s careers were taking off. Sokolov had become a trusted informer on emigré political intrigue for the FBI, and by 1959, he had been hired as a lecturer in the Slavic department at Yale. By 1962, Dudin had become a host at Radio Liberty, a CIA-funded station broadcast behind the Iron Curtain, where he translated scripts into Russian and read them at the mic under the pseudonyms Roman Dneprov and Rurik Dontsov.

At Radio Liberty, according to Alexander Genis, an anchorman at the station since 1984, Dudin became known as an aesthete, a collector of Mexican art, a heavy drinker, an eccentric who carried a dagger at his hip wherever he went, and an unapologetic antisemite. In Genis’s memoir, according to an unfinished electronic draft of a forthcoming English translation that he shared with me, Dudin “defended his antisemitism by explaining that it was instinctual rather than intellectual: Jews simply made him sick to his soul.”

Dudin’s instincts would never impede the trajectory of his career. For twenty years, beginning in 1969, he would work, also under the name Roman Dneprov, as a columnist at the Novoe Russkoe Slovo, discoursing on whatever captivated him––Mexican art, Russian literature, Cold War politics––reporting on his travels around Europe, throughout Germany, Austria, Greece, and Italy, and attending events held by the Overseas Press Club. In 1973, he would join the first executive board of the Congress of Russian Americans, a major advocacy group still in operation today. And for 22 years, beginning in 1967, he taught at Yale, where, soon after his arrival on the faculty, he had also enrolled in a masters’ program in history.

By the late 1960s, Dudin had managed to secure the life of prestige and proximity to power that he had been building toward for more than two decades. But even from his perch at Yale, he was restless, still publicly lamenting the failures of the anti-communist movement he had hoped to lead years before, which by then he believed had been “decapitated.” “A significant part of the formerly very active emigrant intelligentsia became teachers,” he would write in a June 12, 1972, column in the Novoe Russkoe Slovo, possibly with himself in mind, “and, again, with rare exceptions, completely fell silent for fear of causing not imaginary, but quite real, although not official, repressions from their own, usually very ‘liberal’ bosses.”

Dudin’s sense that, by the 1970s, organized emigré anti-communism had no future would never dissipate. Knowing that the movement’s time had passed, he turned his attention away from the fact that it had failed and toward how it would be remembered. In 1979, three years after his longtime friend and former colleague Sokolov had resigned from Yale after the university discovered his Nazi past, he had gotten word that someone was working on a book about the Russian Liberation Movement.

After the war, the Russian Liberation Movement became a convenient short-hand for Russian nationalists who had fought for the Nazis to use to put a gloss on their service to the Reich. They had become Nazi soldiers, policemen, and propagandists, as part of a supposedly independent crusade to restore Russia to its pre-revolutionary glory. During the war, the movement was known as the “Russian Liberation Army,” a force, the scholar Karel Berkhoff writes in his 2004 book Harvest of Despair, covering the history of the Holocaust in Ukraine, that had been a “largely fictional” feature of Nazi propaganda. It had been a fabrication woven into the Nazis’ Russian-language press to drum up Russian volunteers for their war effort, promising them the gleaming badge of the “ROA.” In addition to what was printed in the newspapers, advisors to Andrey Vlasov, the former Soviet general whom the Nazis appointed leader of the fantasy Liberation Army in 1942, Berkhoff writes, made speaking tours throughout Nazi-occupied Ukraine, in an effort to rally the local population to the German side. They were an essential part of the Nazis’ war, part of their campaign to weaken Soviet morale and pave the blood-soaked path to a “Thousand Year Reich” encompassing all of Europe.

Over the course of the war, roughly a million Soviet citizens defected to the Nazis, roughly 100,000 of whom Vlasov’s Liberation Army claimed, without significant corroboration, as its own. The Liberation Army itself, though nominally assembled in 1942, would not have its own divisions until November 1944, when Hitler reluctantly agreed to give Vlasov ten garrisons, of which he was only able to muster two. In the early years of the Cold War, Vlasov would become the idol of many Russian anti-communists in Germany and America, who believed rehabilitating his legacy of collaboration with the Nazis would point the way forward for their new activism in the West and for Russia once the Soviet fell.

“The Vlasovites claimed that Hitler had been the lesser of two evils––and, one senses, by a wide margin,” writes Benjamin Tromly in his book Cold War Exiles and the CIA. “Indeed some of the Vlasovites’ postwar writings places in doubt whether they even acknowledged the enormity of Nazi violence. An example is a SBONR proclamation that excoriates Nazism not for its crimes but for its ‘mistakes’: Hitler’s ‘incomprehension’ of the Russian people’s anti-communism, it argued, allowed Stalin to rally Russians behind the Soviet regime and to win the war.”

Whether the postwar anti-communist cliques acknowledged it or not, the majority of Russians who had fought with the Nazis had done so under the direct command of the Wehrmacht and the SS, often participating in crimes of unimaginable sadism and scale against civilians and prisoners of war. The S.S. Sturmbrigade RONA, christened the “Russian National Liberation Army” by its Cossack commander Bronislav Kaminski, for example, along with other of the Nazis’ Cossack cavalry units, had been deployed in the suppression of an uprising led by Polish resistance fighters in Nazi-occupied Warsaw in August 1944, during which the Nazis slaughtered hundreds of thousands of civilians in the streets, door-to-door, and in mass executions. During the massacre, Kaminski’s Russian National Liberation Army––a unit distinct from, though later absorbed into, Vlasov’s Russian Liberation Army––captured Warsaw’s Radium Clinic, a cancer ward founded by Marie Curie in 1932, mass-raped its nurses and patients, and lit them on fire.

Since the war had ended, in his public writings and private organizing with the SBONR, Dudin had been unyielding in his defense of what he and members of his circle liked to call the “Liberation Movement,” and the book project he was now hearing about in 1979 piqued his interest. The author’s name, he would soon learn, was Catherine Andreyev, then a PhD student at the University of Cambridge who had chosen the topic for her dissertation. As Andreyev, an emeritus professor of Russian history at Oxford, now explains it, she was drawn to researching the Liberation Movement because most of its records were available in American archives, when Soviet ones were closed off, and many of its proponents were alive at the time of her writing and willing to talk. She says that, in writing the dissertation, which would eventually become her first book, published in 1987 as Vlasov and the Russian Liberation Movement, she had hoped to cut a path through the ideological fog of the Cold War and understand the movement from its own perspective.

“Soviet researchers were obviously political and when not denying the existence of opposition to Stalin started from the position that all these people were traitors,” Andreyev wrote to me in an email in July 2022. “Western commentators immediately asked how they could possibly be allied to the Nazis. I was trying to understand how they had got involved and what they stood for.”

In the fall of 1979, while she was doing research for the project at Columbia University, she contacted Dudin, and arranged an interview at his house in Westchester, NY. At first, when they met, he seemed suspicious of her, Andreyev now recalls, peppering her with questions to determine who she knew and might have been working for undercover. “I didn’t know any of their names and thought that was my fault and that I had failed to read some important work on the subject,” she wrote to me. When Dudin was sufficiently assured that Andreyev was only a graduate student, he explained to her whom he was asking about. “All the people he mentioned worked for various intelligence services: US, German and perhaps the KGB as well.”

Over the course of the evening, the two of them spoke in general terms about the Russian Liberation Movement. Dudin, she now recalls, would not discuss the extent of his own involvement in the war. Andreyev would, however, eventually list Dudin in the index of her book Vlasov and the Russian Liberation Movement as a “member of a KONR [Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia] youth organization,” part of the council the Nazis created in November 1944 in the hopes of drumming up Russian volunteers to their war effort.

The meeting got Dudin thinking seriously about the Russian Liberation Movement, especially about who would write its story, and in the months that followed he wrote an essay for the winter 1980 issue of the Russian political quarterly Kontinent. He called the piece “Was it the Vlasov Movement?” and framed it as a call to the aging members of the Russian Liberation Movement not to take up arms but to pick up pens. “The hour is not far off when we shall hear of the death of the ‘last lieutenant’ of the White Movement [defenders of the Tsar against the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War of 1917],” Dudin wrote. “Soon after that the last ‘Vlasovite’ will close his eyes. And the Soviet regime, as well as some people in the West, is eager for that moment to come […] In a word, sit down and write your memoirs, my comrades-in-arms!”

As time raced on, in small West German towns, Ford Foundation offices, open air rallies, back-rooms, emigré newspapers, radio broadcasts, Overseas Press Club events, and Yale classrooms, Rurik Dudin was still clinging to his past, disdainful of a present where his political prospects had dimmed, fearful of a future he suspected would forget him. His service to the Nazis, he would say, had been a political choice inspired not by desperation but his commitment to anti-communism and an “instinctual” hatred of Jews. These were his glory days, self-myths to brag and laugh about behind closed doors and tortuously defend in public. His brother Leo had helped him along, from Kiev to West Berlin and then in New York, where the two of them processed through the institutions of the Cold War, advancing their daytime careers and dreaming of revolution against the Soviets. Striving to remake the world, early on Rurik had abandoned his degree at Heidelberg and his aspirations of becoming an historian to travel to America only to watch his early projects go up in smoke. And as he gained a comfortable life with prestige and access to power, Dudin saw his ideological aims, the same that he had never renounced since the war, come to nothing.

At Yale, none of this mattered. Dudin taught at the university until he reached retirement age, lectured at academic conferences around the U.S., and wrote for major American Russian-language outlets. In the years after the Sokolov case tore the campus apart, neither Yale nor the Slavic department, it seems, initiated an investigation into the possibility that Sokolov had not been the only member of the department to have collaborated with the Nazis. Annual reports sent by the Slavic department to “the President and Fellows of Yale University,” between 1976 and 1980, made available to me by the university’s Manuscripts and Archives library, never mention the Sokolov case. The reports suggest that an inquiry into Sokolov’s time on the faculty, and the possibility that instructors with a similar background were teaching there, was never conducted internally by the department or mandated by the university.

In her memoir, Hanna Holburn Gray, the Provost of Yale College during the Sokolov case, would write that, when she met with Sokolov in the summer of 1976, he “could not be persuaded to accept my plan to institute an orderly internal process to ascertain the facts and deliberate on his status.” When in 1979 the DOJ requested internal university files on Sokolov, the university adopted the same posture, saying it would be up to Sokolov to grant federal investigators permission to view select documents or the Department would have to subpoena them.

This shroud of confidentiality still surrounds the history of admitted Nazi collaborators in Yale’s Slavic department in the mid-20th century, so much so that nearly all current faculty in the department, according to Edyta Bojanowska, the sitting chair, have never heard of Sokolov or the scandal surrounding his resignation.

The university explains this far-reaching lack of knowledge of what happened 50 years ago as a consequence of its records access policies. “Correspondence between members of the Provost’s Office and members of the faculty is confidential,” wrote Scott Strobel, the current Provost of Yale College, in an email response to my request for information on the Office’s handling of the Sokolov case and whether any of its internal files on the subject are viewable. “Therefore, I am not able to provide you with access to any private communications that may or may not be in the Provost’s Office records within the University Archives.” When I then asked in a follow-up email whether the university has ever conducted or contemplated retroactively conducting an investigation into the presence of admitted Nazi collaborators on the faculty of the Slavic department in the mid-20th century, Strobel replied: “Not to my knowledge, no.”

Zachary Groz is a junior in Jonathan Edwards College and a former Editor-in-Chief of The New Journal.

Collage design by Kevin Chen.