“Four days a week I was going to church,” Holly Nichols told me in the nave of the United Church on the Green. “They waited a year and a half to tell me I was going to Hell.”

Nichols has been religious since the age of six or seven, when she first attended Lutheran services in Hamden with a childhood friend. She described to me how being in church continues to give her a peace she cannot find anywhere else. Despite her love of God, she has struggled to find a church that accepts and affirms her as a lesbian.

About six months before we spoke, Nichols had been attending a non-denominational church in North Haven. She’d been there for around a year—involved with Bible study, prayer group, and services—when she brought her wife to a Sunday service. Shortly after, she told me, one of the five church alders told her that being married to a woman was a sin and that she had to repent. Nichols brushed it off as just one person’s opinion rather than that of the church. But she did not bring her wife back again.

The next intervention came when Nichols attended membership class, hoping to become an official member in the church after more than a year of devoted attendance and financial support. But before she entered the church, a member at the door warned her that she couldn’t become a member if she was gay.

“I think I was in denial that they were going to take it as far as they did,” Nichols said. “I thought they were just trying to make a point, but I didn’t think it would stand in the way of my becoming a member or eventually my being able to attend.”

In September 2022, a year and a half into Nichols’ time with the church, the congregation staged a third, full-on intervention for her. Four alders—those with long-term experience and standing in the church—and two long-standing members surrounded her in a room.

“They went around in a circle and told me why my marriage was wrong, why I was going to Hell,” Nichols said, growing quieter. “And that did test me.”

After that final intervention, Nichols decided to leave that church. She first took some time away from formal religious spaces, instead investing in her personal prayer life, journaling, making gratitude lists—even skydiving.

“It’s traumatizing to be told that you’re rejected by God,” Nichols said. “It was really hard to feel like it was safe to go back to church.”

After a few months, Nichols began seeking a new worship community, but found it difficult to locate an affirming church. Her search, mainly directed by Google hits, led her to one dead end after another, including uninspiring Zoom-only services and an empty parking lot where a church had once been.

Perhaps the most overt condemnation appears in Leviticus 18:22: “You shall not lie with a male as with a woman; it is an abomination.”

She started attending the United Church on the Green a little over a month before we met. One of her Google searches for an “open and affirming” congregation had finally worked.

“Open and affirming” is a designation created by the United Church of Christ (UCC)—the national Christian denomination to which the United Church on the Green belongs—to assert the full inclusion of LGBTQ+ congregants in church life. The label means not only welcoming queer congregants into the church, but also affirming that their lives are not in conflict with the Bible’s teachings.

In practice, “open and affirming” churches fall along a spectrum; some churches incorporate it as a tenet of their community philosophy, while others—according to some queer churchgoers—appropriate the phrase as a means of drawing in new members. UCC is a congregational church, which means it’s much less centralized than other Christian denominations like Episcopalian, Presbyterian, and Catholic churches. Because of this decentralization, each local UCC congregation can determine its own policies and practices, including whether to adhere to suggested national guidelines. This includes approaches to queer affirmation. State by state, county by county, each congregation exercises their own discretion around inclusion.

Standing by the light-filled pews at the back of the church, Nichols smiled as she told me about bringing her wife to United. She hopes to reintegrate church into their lives together.

“It’s a fresh start without that negative nagging, enemy voice telling me this is what makes me not good enough or this is what separates me from God that they were feeding me at the other church,” she said, as she relaxed her fidgeting hands. “Here I don’t have that. I have peace.”

Nichols’ experience with homophobia in the Church is not unique. Christian spaces and teachings have notoriously created violent and traumatic experiences for members of the LGBTQ+ community—in Connecticut and beyond. But Nichols is also not alone in her persistent desire, as a queer person, to find a Christian community despite these hostile encounters. For the LGBTQ+ members of New Haven and Yale’s religious community with whom I spoke, creating queer spaces and forging new meaning in the church means adapting old traditions and reexamining conventional readings of the Bible. Many say their queerness and spirituality enrich each other.

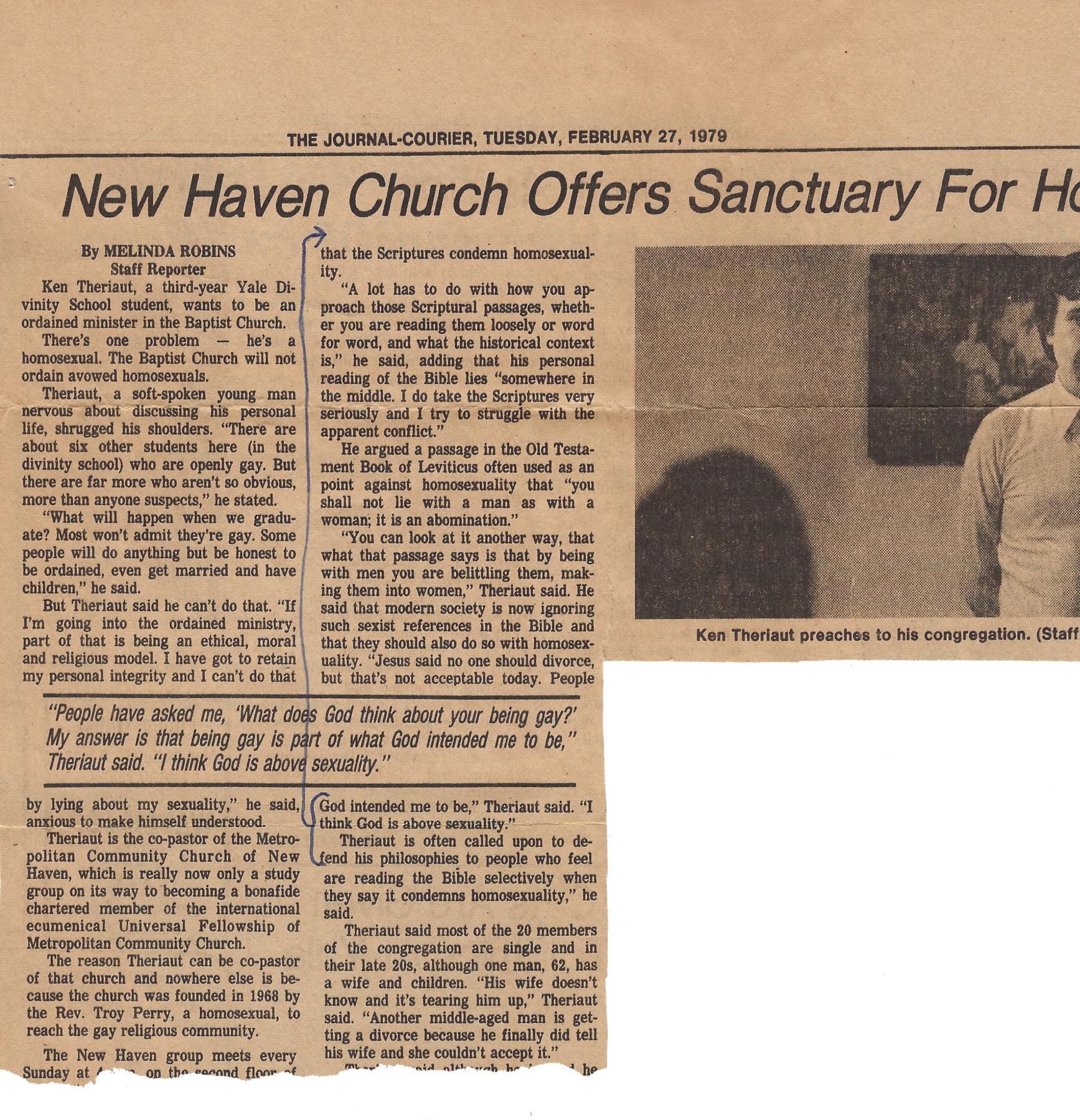

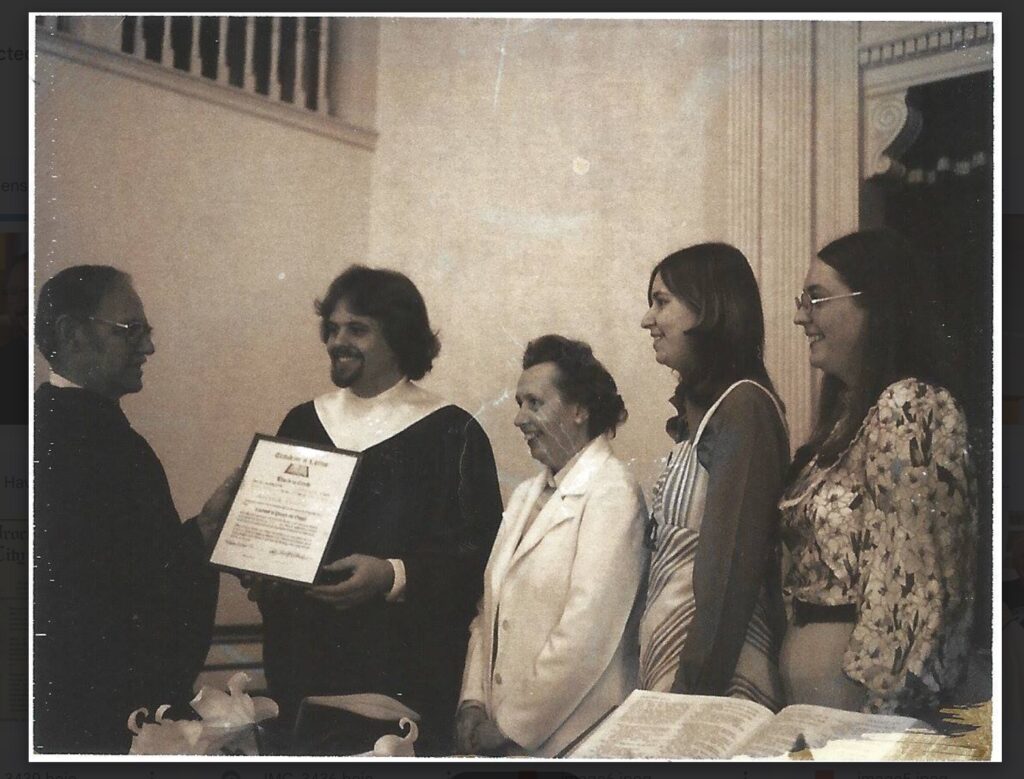

Ken Theriault, second to left, receives his license to preach in 1978.

Reclaiming the Bible

To exist as a queer person in a Christian space is to stand up against generations of canonized, homophobic dogma. Despite newer, affirming interpretations, many church leaders still weaponize the Bible to condemn homosexuality. They often ground these attacks in what have become known as the “clobber passages,” those most cited to condemn LGBTQ+ people as heretical. Perhaps the most overt condemnation appears in Leviticus 18:22: “You shall not lie with a male as with a woman; it is an abomination.”

Congregants I spoke with had varying reactions to these texts. Some cited other archaic rules in Leviticus—like prohibition of eating shellfish or mixing fabrics in one’s clothes, and a decree ordering menstruating women to leave city limits—as proof that some homophobic Christians selectively punish queer people over those who commit other listed abominations.

Others see the process of interpretation as one that changes over time. There are a growing number of theologians who are reading the Bible—particularly these “clobber passages”—with a new lens that recasts them as condemnation of other sexual wrongs, like rape or incest, rather than being overtly homophobic.

“I’m not going to look at it as this perfect document that has been delivered to us today, as it exactly was when it was written,” Cal Swanson ’25, a co-chair of the Episcopal Church at Yale (ECY) who is also queer, told me. “I’m going to look at it as an artifact that has been through centuries of interpretations and changes.”

In the face of the Bible’s weaponization, many of the queer people I spoke with explained how the text could be reclaimed as a powerful tool of love and affirmation. Most told me they blamed the misinterpretation of Christian teachings for the harm they faced, rather than the tenets of Christianity. Queer churchgoers generally hold the fundamental belief that God is good, loving, and just—even when church doctrines don’t reflect that.

Rev. Aaron Miller is a transgender man and a pastor at mcc in Hartford.

“The greatest harm we have ever done in religion is to not say love yourself first, and you are lovable, and loved,” Rev. Aaron Miller, a transgender man and a pastor at the Metropolitan Community Church (MCC) in Hartford, tells me. “That’s the thing I say over and over again because if you’ve heard it a million times, I want you to hear it a million from me. Because you’ve been lied to.”

Miller was confirmed as a Lutheran and attended Catholic Church for nearly a decade with a former partner. He left the Catholic Church for a number of years before eventually returning to religion and attending Yale Divinity School, graduating in 2008 and working in pastoral care at Yale New Haven Hospital. Then he started attending and later working at MCC, a denomination founded in 1968 by a gay ex-Pentecostal minister explicitly for queer people to worship together.

At the beginning of our conversation, I told Miller—just as I told everyone I spoke to—that I am a lesbian who was raised Episcopalian, having grown up seeing sexuality and religion in fundamental tension with each other. Like the others, he was quick to try to persuade me otherwise.

“You have to really do gymnastics to ignore us in the Bible—the queer folks in the Bible,” he told me, referencing specific passages in the scripture that lend themselves to queer-affirming interpretations, including what he interprets as same-sex romantic relationships and trans representation.

“It was the gay community wanting to worship with itself,” Theriault explained.

He told me about Jonathan and David, and Ruth and Naomi. He described them as the only romantic couples in the Bible, both of whom are same-sex. Ruth’s vow to Naomi, he said, is even commonly used at straight weddings. He went on to explain readings of transgender identity in the text, telling the story of Genesis 1:27—“So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them”—as connoting not separate beings but the fact that we contain the potential for both genders within us, embodying spectral identities.

“It’s so strange to me that this is the same text that’s used against gay people,” said Rev. Ali Donohue, chaplain at the ECY and a lesbian. “It’s so clear to me how much of this message is helpful, and familiar, and home.”

Creating Space

As older churchgoers were quick to remind me, to come out as queer even as little as fifty years ago could result in anything from forced exile to social isolation in any given church, depending on its denomination.

In 1975, Ken Theriault, then a 21-year-old junior at Yale College, came out as gay. Theriault had been raised American Baptist, “singing in church choir since they had a robe small enough for me.” He began studying at the Yale Divinity School, hoping to be ordained in the American Baptist Church even as it became clearer that he would not be able to serve in their ministry because of his sexuality.

Alongside Beverly Lett, a fellow student at the Yale Divinity School, Theriault founded a new branch of MCC in New Haven in 1977. The expansion filled a void, Theriault said, creating a space of formal LGBTQ+ religious acceptance in New Haven at a time where no churches allowed or affirmed queer worshippers and leaders.

At its first meeting, MCC New Haven met in the small upstairs parlor of a local Methodist church. There were about fifteen attendees, most of whom had heard about the church through word of mouth or the MCC Hartford newsletter, Metroline. MCC New Haven also joined with the New Haven chapters of Integrity and Dignity—an Episcopalian and a Catholic gay religious group, respectively—for monthly potlucks at members’ homes.

Al Forino, right, and his husband, Eric, following their marriage vows at the United Church on the Green.

From 1977 to 2015, MCC New Haven moved across several churches and hosted anywhere between twenty and one hundred congregants a week.

“It was a real church. Just the population was a little different,” Theriault told me. “A place to gather and sing and hear sermons, I mean it was a regular church service. We weren’t playing church.”

Theriault found that even though local churches weren’t openly affirming of queer people yet, they accommodated Theriault and Lett’s requests to meet in their space, often for free.

“It was the gay community wanting to worship with itself,” Theriault explained. “Just the fact that there were three congregations that were willing to house us, and saw that as important as part of their mission—there was some acceptance there.”

The church advertised through word of mouth, as well as what Theriault called a “bar ministry,” in which members recruited patrons of local gay bars like Partners Cafe and passed out leaflets advertising the church. Later, the church accrued more formal local coverage, including a 1979 profile of Theriault in the New Haven Register entitled “New Haven Church Offers Sanctuary for Homosexuals.”

Rev. Jocelyn Cadwallader is a pastor at the First Presbyterian Church of New Haven

“I would say most of us came with some negative experience, and that’s why we’re looking for something else,” Theriault told me, forty-four years later. “People still have their spirituality and want to express it somehow.”

Participation at MCC New Haven eventually dwindled. Co-founder Lett left in 1979, and the church struggled to hold down a permanent location or pastor. As more of New Haven’s churches became accepting of queer worshippers in the early 2000s, the need for a specifically queer church diminished, and social schisms proliferated within the MCC. Today, there are no gatherings of MCC in New Haven—parishioners can join the MCC Oasis Zoom group or travel forty-five minutes to Hartford.

MCC still exists—across the United States and twenty other countries—but it faces struggles unique to being a queer church amid a broader landscape of declining church membership and aging parishioners. A lack of an endowment or the security of a historically owned space makes stability nearly impossible, explained Sharron Emmons, a member of the Board of the Directors at MCC Hartford and a lesbian. She added that the historical lack of queer families—and thus the opportunity to raise children in queer churches—hurts growth.

The first time he attended a service at United, he remembers, he was so overcome by emotion that he cried through the whole sermon.

“Early on, if you wanted to go to church, [MCC] was the church you went to, unless you wanted to be closeted. But as different congregations opened up, now you didn’t really need an MCC,” said Cathy Vitelli, a lesbian and former member of MCC New Haven who moved to an Episcopalian church. “You’re more comfortable there. [But] you could find a community someplace else.”

Finding God, Again

While most of the queer churchgoers I spoke with cited affirming interpretations of the Bible as helping them reconcile their faith and queerness, they stressed the greater importance of church as a site of that interpretation and burgeoning community, one that could transcend the text itself. The physical space and communal tenets of a church could provide shelter, refuge, and community in a way that the Bible alone couldn’t.

“I don’t know if it’s because we’ve been deprived of religion for so long, but there’s more of a yearning for it in the [LGBTQ+] community,” Alfred Forino, Moderator at United Church on the Green, tells me as we talk over coffee.

A skinny wooden cane, with a handle carved into an ornate crocodile head, leans against his chair—this is his lucky charm. At sixty-five years old, Forino has been a member of United for twenty-three years. The first time he attended a service at United, he remembers, he was so overcome by emotion that he cried through the whole sermon.

Rev. Ali Donohue, chaplain of ECY, with her wife Rev. Kerith Harding and their two kids.

Forino is gay. Like many queer people, he has navigated a complicated relationship with church.

“Growing up as a Catholic, I was very lucky that I had a good enough sense of my own self because what I heard from the pulpit was just homophobia,” Forino said. “There was a brief time where I prayed to change, [but] I realized very quickly that wasn’t going to happen. But I also had enough self worth to know that God made me this way.”

Forino ended up marrying his husband, Eric, at the United Church on the Green in 2005, three years before it was officially legal in Connecticut and ten before it was federal law. He was quick to point out to me the significance of having a church recognize the validity of their partnership before the government did.

Rather than leaving church altogether when they faced homophobia or belittlement, the queer Christian and religious people I talked to were determined to keep pushing for a church that would accept them—whether that meant encouraging their church to be more affirming or searching for a new one altogether.

“The church is a community where people can gather together and worship God and seek to be faithful to God. But it’s also flawed and very human,” Rev. Jocelyn Cadwallader, a lesbian pastor at First Presbyterian Church of New Haven, told me. “I’ve always been very clear of separating those two things: that the church is not a God.”

Cadwaller learned this distinction firsthand. She was raised Presbyterian and had been involved with her local church from a young age. Despite the fact that the national Presbyterian Church at the time did not allow openly queer people to be clergy, Cadwallader still felt compelled by God to serve in the ministry as a priest, and attended seminary school in 2004. She emphasized a commitment to staying within the Presbyterian denomination, despite its nationally hostile regulations, because her local church community had helped raise her and always supported her.

“I never felt interested in moving somewhere different for the sake of my own sexuality,” Cadwallader said. Instead, she hopes the denomination will grow into what she feels God calls the church to be—affirming of all its congregants.

There is definitely still defiance of like, I’m not going to let them have the Church,” she said, referring to homophobic Catholics. “They’re going to have to deal with my baptized ass as well.”

Many queer congregants I spoke with emphasized Cadwallader’s idea of church as a pillar of community and an extension of their social, cultural, and familial history. This belief can be especially strong with queer Catholics.

“I see the Catholic Church as not just something you hop in and out of as you sort of church shop. I see it as a community to which I belong,” said Stephen McNulty, ’25, a gay Catholic at Yale and an active member of the LGBTQ+ Ministry at St. Thomas More (STM), Yale’s Catholic chapel.

McNulty echoed an idea shared by others: abandoning the churches he’d grown up in because he was queer could feel even more wrong than staying in a non-affirming denomination.

Jacquelyn Oesterblad YLS ’22, a Catholic and lesbian who helped found the St. Thomas More LGBTQ+ Ministry, believes that she is showing respect for the Church by thinking it has room for her. “There is definitely still defiance of like, I’m not going to let them have the Church,” she said, referring to homophobic Catholics. “They’re going to have to deal with my baptized ass as well.”

Oesterblad stressed the importance of queer representation even in non-affirming spaces, which she noted will inevitably host new generations of queer children looking for role models.

“As long as queer kids are being raised in this church—and they will be—I think it’s better for them to see people like me in the pews than to not,” Oesterblad told me. She emphasized she does not try to recruit queer people into the Church. Instead, she works with others just like her: baptized Catholics trying to navigate hostile yet familiar spaces.

While McNulty and Oesterblad are not alone in their identities, many of the queer people with whom I spoke who were raised Catholic ultimately left the denomination for a variety of reasons. Some, like ECY’s Rev. Donohue, realized that, despite their love of the faith, it would not make room for their marriage or official ordination. Others, like Forino, were unwilling to endure homophobia and partial membership due to their sexualities.

Rev. Jocelyn Cadwallader holds her daughter while in the pulpit, and her son is crawling up in the foreground.

In New Haven’s affirming churches, some queer churchgoers disregard the religious element of church altogether, staying for the welcoming community and its benefits for fostering queer connections and social justice.

“From a Christianity and believing-in-God point of view, there’s none of that there for me, it’s not what works for me,” says Emmons, who has spent decades at both MCC New Haven and MCC Hartford despite being an atheist.

“But I’ve seen the church save lives. People come to our church, broken—older people, especially because it was tougher in the past—where they were kicked out of their families, kicked out of their churches,” Emmons adds. “Our message is ‘come out, come home, and come back.’ Here’s a place where you can re-find your God.”

And many queer people are intent on doing just that. I was shocked by the number of queer religious people I stumbled upon—young and old—in churches at Yale and New Haven. At the United Church on the Green alone, I chatted with three queer churchgoers out of a crowd of around twenty people.

One of them was Darnel Ray, a middle-aged gay man who sat in the pew in front of me and hummed “mmhmm” in agreement throughout the service. Having been raised American Baptist, Ray continued to crave Christianity even after his coming out was a source of conflict between him and his parents. Years later, in 2019, he saw the pride flag outside of United and decided to try it out. He’s since moved to West Haven but still commutes about twenty-five minutes for services. He’s unsure if the church closer to where he lives is accepting, and he’s nervous to find out.

From the Altar

As more openly queer individuals join religious communities, queer leaders face a dilemma: do they spearhead progress towards greater acceptance or seek out already affirming spaces? Some, like Donohue and Cadwallader, opt for churches that have made strides towards inclusion. Others, like Oesterblad and McNulty, find that the nature of non-affirming spaces thrusts them into leadership roles since their mere presence challenges the status quo. This tension between leading change and seeking acceptance animates church communities at New Haven and Yale.

Donohue noted that she and her wife, who is also an Episcopalian reverend, choose local churches that are already affirming. But this choice only came after Donohue left the Catholic Church, in which she’d been raised and educated for decades of her life.

MCC Hartford aims to protect and support the local queer community.

“I experience [queerness and religion] as a source of strength, I observe it as a source of pain,” Donohue explained, noting the queer students she’s worked with at Yale are often the ones struggling the most. “My only hope is that I’m able to have people join me where I’m standing, because I see zero conflict.”

At Yale, there are only four explicitly affirming Christian groups out of twenty ministries, explains Rev. Jenny Peek, an Associate University Chaplain and lesbian. “Explicitly affirming” here means believing in the full inclusion and affirmation of LGBTQ+ people (including celebrating queer marriages and ordination) and advertising themselves as such. These groups are the Episcopal Church at Yale (ECY), the University Church at Yale (UCY), LuMin at Yale, and Yale Progressive Christians Students. Peek added that the landscape can sometimes be difficult for incoming queer students to navigate.

St. Thomas More walks a thin line when dealing with queer students as a Catholic university chapel. The church can—and does—welcome queer students, but it cannot formally affirm them in their ability to live out their queerness, particularly in sexual relationships. This would be a violation of Catholic teachings.

Oesterblad recalls being thrust into a leadership role for the LGBTQ+ Ministry at STM—a ministry affinity group founded during the pandemic—as one of the few openly queer people in the church. Laughing, she remembers wishing she could join an already existing space: “Can I just plug into something that already exists and be ministered too, please?” Oesterblad ended up helping to create, design, and lead the ministry.

In the midst of this landscape, queer chaplains at Yale can offer a beacon of representation and affirmation. “Knowing that she’s queer and she has this amazing understanding of the Bible being about love and being about affirming your LGBTQ identities is so helpful for me,” Swanson said of Donohue, who leads his church. “I feel like I absorb some of my certainty about it from her. And so I think it’s been a big thing having a queer chaplain.”

Outside of Yale’s walls, queer reverends often engage in the same kind of affirmative work, though for a much broader audience—not just young adults. But the pastors I spoke with noted that the churches that call these queer leaders are often already accepting and progressive.

Rev. Cadwallader of the First Presbyterian Church recounted a time that a congregation offered her a job with the disclosure that about half of the congregation was not ready for a queer pastor. The hiring committee hoped she could change their minds. She ultimately turned them down: “I’m not in the business of splitting churches…That journey needs to be done by somebody else.”

But not every queer member of non-affirming spaces feel that they have a choice.

“I’ve often been the one who starts conversations,” McNulty said of his work at the STM’s LGBTQ+ Ministry. “And I’m okay with that.” He starts these conversations with a contradiction he says he incurs “by virtue of existing”: being a gay Catholic.

Ultimately, queer religious leaders across New Haven can usher in a more accepting space, buttressed by the virtue of representation. Cadwallader says her queerness is a strength when she preaches to all her congregants—even those who aren’t queer.

“I get to remind them again about who Jesus is in their lives and why Jesus is important,” Cadwallader said. “And they tend to listen to me because I am the voice of the one that was told for so long that I shouldn’t be there.”

Coming Home

“Do you have a church home?” Nichols asked me when we first met in the nave of United. She echoed the common language of many that I spoke with—a church where I could belong, be affirmed, and return to, no matter where I was in life.

I told her how I had grown up in the Episcopalian Church, but now I was more of a Christmas and Easter Christian. I worried I’d stopped believing too soon, and I didn’t know if there was a future path for me.

After we finish talking, I thank her for opening up about her story. She looks at me, holding eye contact as I close my notebook. I have a strange feeling, like I’m about to cry.

“I hope this project opens your eyes to whatever it is you need to see,” Nichols says. “I hope you find whatever it is you’re searching for.”

I think I’m starting to see. Perhaps more than queer people seeking and finding religion, I’ve found them reclaiming it—coming home.

Abbey Kim is a sophomore in Branford College and an Associate Editor of The New Journal.