In the early morning of June 6, 2007, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials swooped into New Haven, handcuffs at the ready, searching the city for undocumented residents. By the end of the raid, they had taken thirty-two people off the streets of Fair Haven or from inside their own homes. Families gathered in a local church to record the names of those missing.

The arrests shook the community and even prompted a response from the mayor at the time. “Children have been traumatized; civil rights have been trampled; U.S. citizens and legal residents have been stopped and questioned without cause; and families have been ripped apart. America is better than this,” Mayor John DeStefano wrote in a letter on June 11, 2007, to Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff.

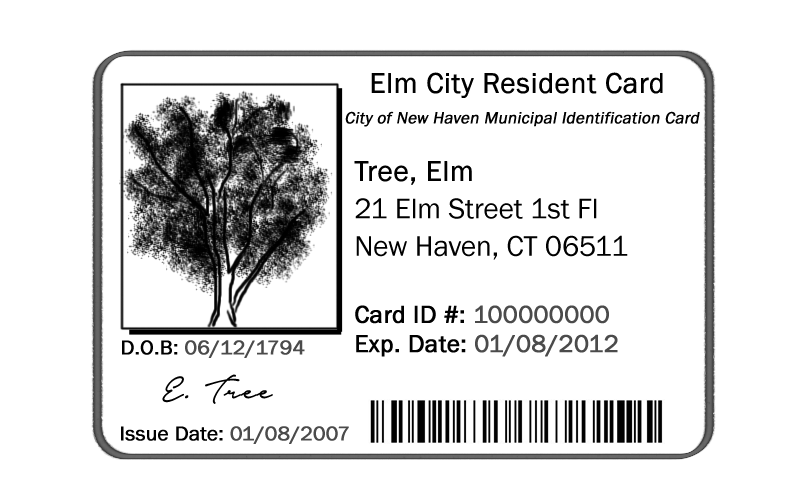

The appearance of dark-jacketed ICE agents was a startling setback for grassroots groups, whose advocacy on behalf of the city’s 10,000 to 15,000 residents without valid U.S. documents had been gaining momentum after years of work. The arrests came just two days after New Haven’s Board of Alders voted to create the nation’s first municipal ID card. The Elm City Resident Card, as it was called, serves as photo identification for residents regardless of their immigration status.

The card was created with a few specific goals in mind. Undocumented immigrants, unable to open bank accounts, often carried or stashed large amounts of cash, making them prime targets for robberies. The card would allow them to present identification at banks, open accounts, and store their funds safely. They would also be able to check out books from the city’s public libraries and enter public parks and beaches. And, since the government itself would issue the card, officials hoped that cardholders would feel comfortable approaching local police to report crimes.

“The Elm City card was a shot heard around the country for many of us trying to resolve these problems for low-income and immigrant groups,” says Dr. Paule Cruz Takash, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. New Haven, with a current population of about 130,000, was the first major city to offer a municipal ID card, and several other cities have since followed in its footsteps. San Francisco started its own program in 2009, and, as of July of this year, more than 21,000 people had obtained cards. With Takash’s help, Oakland, California, developed an ID that doubles as a debit card. Nearly 5,000 people have received the cards since February 2013. Los Angeles and New York City are also in the process of preparing their own versions of the project, and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio signed legislation for IDs this summer, with plans for the city to roll out the card by January 2015.

The idea for a municipal ID wasn’t exactly born in New Haven. Years before the Elm City ID’s arrival, similar identification systems already existed in other parts of the country, according to “A City to Model,” a 2005 proposal crafted by the community groups JUNTA for Progressive Action and Unidad Latina en Acción, with the help of Yale Law School students. Florissant, Missouri, a town of about 52,000 people, offered a resident card to anyone who could provide photo ID and a utility bill. The card provided access to community centers and local recreation facilities. Aventura, Florida, a town of about 37,000 people, issued cards for access to parks and city-sponsored programs to anyone who could provide proof of residence.

The Elm City Resident Card did not have revolutionary ambitions, according to Michael Wishnie, who runs the Workers and Immigrants Advocacy Clinic (WIRAC) at the Yale Law School. But the New Haven proposal went beyond recreation. It asked local police and businesses to accept the card as a form of identification. And it had another important goal: It would allow people to open bank accounts. This innovation made it the first municipal ID in the country with implications for residents’ economic livelihoods and legal concerns. Suddenly, New Haven was making the national news.

While New Haven still receives credit for being the city that led the way in the ID debate, its program is getting less attention these days, and the number of sign-ups has dwindled. To date, over 12,300 people have signed up for the card, but nearly half did so in its first year. Decreased press coverage and the disappearance of mobile sign-up units may have contributed to the slump in numbers. In 2013, there were only 1,234 cards issued. About 550 Yale students signed up as part of a “New Haven Solidarity Week” in the fall of 2007, demonstrating that the card was meant for all residents, not just undocumented individuals. But many current students have never heard of the card. With limited use across the city, there is a renewed concern that the card will become a sort of scarlet letter for the undocumented.

It also turns out that some just won’t buy into the city’s dream. Major banks do not accept the card, so the problem of “unbanked” residents remains unsolved. When customers try to pay for purchases with a check or credit card, businesses sometimes refuse to accept the card as a valid form of identification. The ID was never reformatted to work with the city’s current electronic parking meters, and the original proposal to make it a low-value debit card never took off.

Yet, as far as former Mayor John DeStefano is concerned, the federal government is the one making the mistakes. When I met him for coffee on an April morning, he calls its immigration policy “fundamentally broken and incoherent.” Dressed in a white shirt and a grey suit appropriate for his job as Executive Vice President of Start Community Bank—one of the few that fully accepts the Elm City Resident Card—DeStefano tells me that his aim was always to create “an open and welcoming community.” His smiling face appeared on the first sample ID, dated May 7, 2007, below the banner: “New Haven: It All Happens Here.”

In his view, New Haven took a bold stand against the federal giant. Complicating the matter, the government did not act with a single voice; even when the Attorney General and other federal agencies approved plans for the card, the Department of Homeland Security remained wary. Chertoff, the Secretary of Homeland Security, told the Yale Daily News in April 2008, a year after the card’s aldermanic approval: “I don’t think that having identifications to enable people to live illegally is a good thing…It’s inconsistent with the law as we have it.”

When I contacted DHS to ask about the current policy toward municipal IDs, the e-mailed answer dodges the question. “Secure driver’s licenses and identification documents are a vital component of our national security framework,” reads the brief I received on the REAL ID Act, which Congress passed in 2005 in response to the 9/11 Commission to set standards for state identifications. However, the Elm City Resident Card was never meant to address the act’s goals: to regulate access to federal facilities, nuclear power plants, and commercial aircrafts. The response suggests that DHS disapproves of the numerous rogue states—not including Connecticut—that fail to follow these national standards, but the department may have bigger problems than one small city’s outdated project.

***

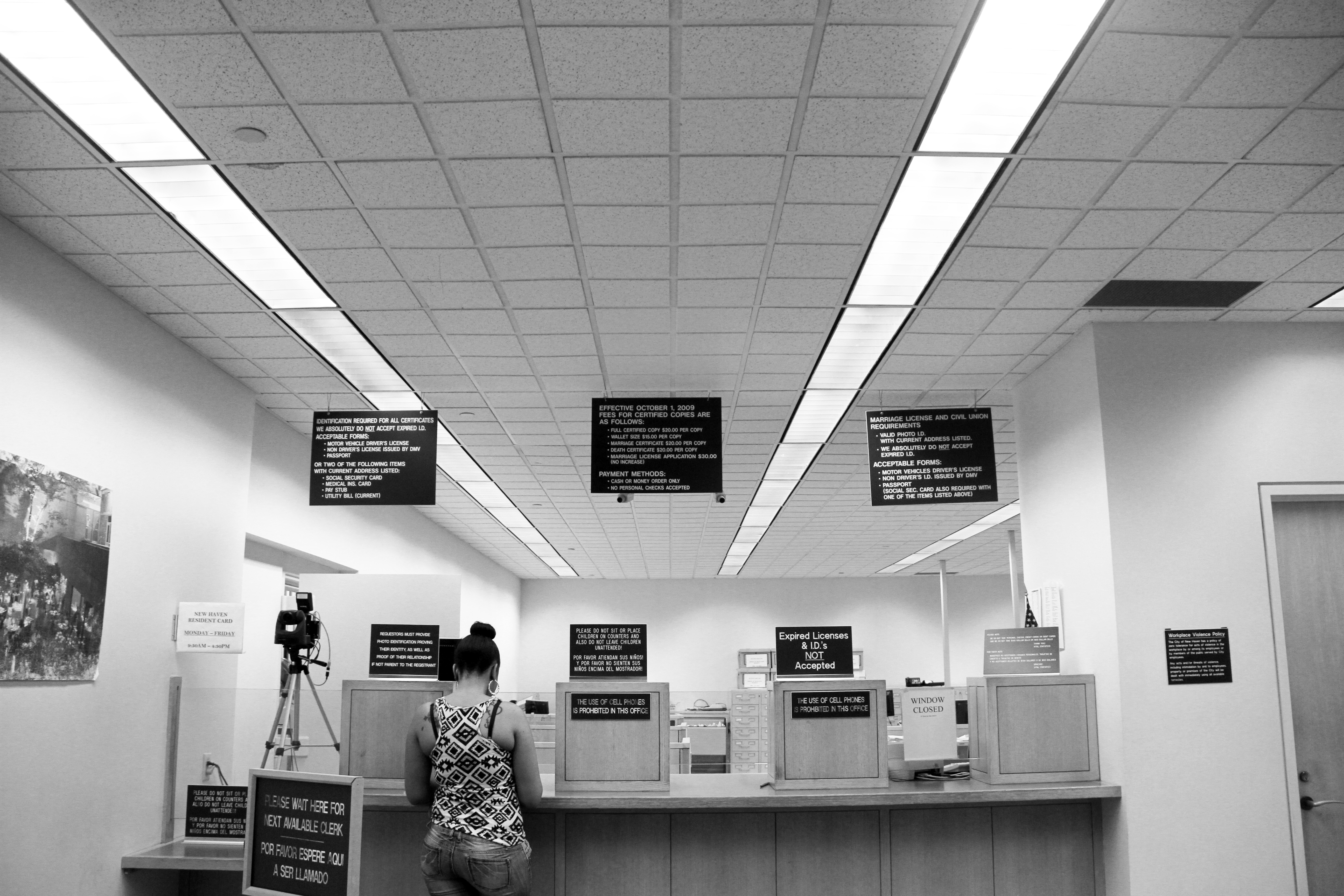

The Office of Vital Statistics, where the municipal ID cards are issued, is on the ground floor of City Hall. A plain sign above the door matches the bland interior, spruced up with a couple stock photographs of New Haven. People line up, waiting for help from clerks. Blue signs located above the counters dictate general rules—“Expired Licenses & ID’s NOT Accepted.”—in large white letters.

Applications for birth certificates, marriage licenses, and death certificates are available at the center of the room, as though one can sort through all of life’s milestones with a series of forms. For those interested in an Elm City card, a yellow paper to the left states that a card can be obtained with a valid photo ID and two pieces of mail. A tripod points outward, ready to take quick snaps of applicants. The cards, which are valid for three years, can be issued on the spot, Monday through Friday, 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Passports, birth certificates, drivers’ licenses, national identification cards, consular IDs, voter registration cards, and visas can be presented as proof of identity. Applicants must also provide proof of residence: insurance and utility bills, bank statements, employment pay stubs, property tax statements, school enrollment forms, voter registration cards, or forms from a New Haven health or social services organization will work.

The office is quieter than it was in July 2007, when people lined up out the door to get the first Elm City Resident Cards; now, a few people wander in ahead of me to the wooden counters where staff wait, though none head over to the photo corner. According to office director Lisa Wilson, there is no accurate record of the number of cards issued each year since 2007, because the office’s software can’t crunch the numbers that far back. Though she provided me with a total from the past year, she insists that she is unable to track the annual changes in registration numbers. Still, the department’s website and the downloadable application form suggest a certain sleepiness in the office; they lack, for example, consistent information about the hours during which an applicant can obtain the card, as though there is nobody ensuring they are updated.

The lines are generally short, and for those who do come in, getting the card is easy. The staff does not ask for any information beyond residents’ full name, date of birth, and address, in addition to the required documents. According to Wilson, employees do not compile information about residents’ demographics, immigration status, or area of residence within New Haven. In essence, they operate with a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy, but without any fanfare. However, the online application, which is more detailed than the single page I get at the office, hints at the threat that follows some applicants: “Would you like the City of New Haven to keep confidential your name and residential address as listed in this application to the extent permitted by law?” Applicants check a box: “Yes/Si” or “No.” Employees do not keep copies of the identifying documents, such as passports or consular IDs, or proof of residence, such as utility bills or employment pay stubs. They collect ten dollars from each adult applicant and five dollars from each child. Then they move on and assist the next person in line.

Neither the city nor the police nor community groups collect information on which ID card holders lack federal U.S. documents. If those who continue to sign up are indeed the immigrants who stand to benefit most from it, the card may have achieved some of its goals. Martha Okafur, who started as Community Services Administrator in June, said her department is in the process of assessing what still needs to be done to help the unbanked, and plans to discuss with banks their reluctance to accept the card. But without the data, the only way to find out what’s really going on is to speak to members of the community.

***

Ten years ago, chances are that I would have been mugged on my bike ride to Fair Haven, says neighborhood resident Ruben Mallma, an organizer for the immigrant rights group Familias en Camino. Crime rates in the area were higher back then, and he credits the ID for contributing to a sense of safety in his neighborhood.

Fair Haven, the city’s immigrant hub and home to thousands, is the place to watch when following New Haven’s progress on immigration issues. It is difficult to obtain accurate figures, since undocumented individuals may be wary of officials who are collecting population statistics. But according to “A City to Model,” approximately 3,000 to 5,000 people in Fair Haven are undocumented. About half of the neighborhood’s population is Latino, with people from Mexico, Ecuador, Peru, and surrounding countries.

Mallma’s stories illustrate the difficult realities and daily problems that the ID card attempted to address: Residents without bank accounts were often robbed, and were too fearful of the police to report the crimes. He knew of eight people living in a three-bedroom apartment in Fair Haven whose three-bedroom apartment was burglarized ten years ago but they did not tell police. Another man got off a public bus with the money from four paychecks in his pocket. He was chased by a thief until Mallma pulled him into his house. Since police were often not alerted about these crimes, they could not keep accurate statistics. But newspapers reported that the undocumented were called “walking ATMs,” and people kept track of the situation through stories passed from one neighbor to the other.

Many of the city’s undocumented have little hope of obtaining citizenship, unless they are able to marry a U.S. citizen or find an employer to sponsor them. So they find ways to conceal their status. Two decades ago, many of the people Mallma knew carried fake documents. Some had papers from people who were deceased in other states. Others used their IRS tax identification numbers instead of Social Security numbers. Living in the shadows, people couldn’t help but feel that they didn’t quite belong in the community.

“When the police knock on your door, or when the police stop you for driving your car without a driver’s license, or when you try to buy something by credit and you are denied, you think, ‘What am I doing over here?’ You, as a person, you are nothing,” Mallma says.

David Hartman, the media liaison for the New Haven Police Department, states that when the Elm City Resident ID Card was first implemented, the number of burglaries and robberies reported in Fair Haven increased—and the police actually found that encouraging. The change suggested that people were more willing to report crimes. Overall crime rates dropped across the city in following years, and Hartman says that the ID card was part of the change. With more people turning to the police, “those people that were perpetrating these crimes realized that their descriptions were going to be out there,” making it more likely that they would be apprehended. Indeed, crime reports for the county show that the robbery rate dropped steadily after 2007, while the burglary and larceny rates jumped by several hundred in 2008 and then returned to lower levels. However, it is all but impossible to determine if the Elm City card was the primary cause of these changes.

***

At a small meeting of Unidad Latina members in April, I seat myself next to John Jairo Lugo, the bearded organizer whose name often appears in news articles about the latest immigrants’ rights protests. Unidad Latina, founded in 2003, is the new kid on the block, as far as Latino rights organizations go; its collaborator, JUNTA, which also works on issues affecting the Latino population, has been around since 1969. But there are still over twenty people gathered in the long, wood-floored room in the New Haven People’s Center on Howe Street.

There is an old A.B. Chase piano in the corner, next to the whiteboard where Lugo stands with a dry-erase marker in hand, poised for discussion. The walls are adorned with a black-and-white image of Rosa Parks, a poster commemorating “America’s Labor Heritage,” a painting by the Mexican artist Diego Rivera, and a collection of children’s drawings on colored construction paper with messages addressed to “Dear Mayor Toni Harp.”

Knowing that I came to hear people’s stories, Lugo turns to one of the other early arrivals and says, in Spanish, “Marco, you have the ID card, right?” When the skinny man next to me assents, Lugo grins: “Your first victim,” he says to me, before turning back to the man. “Only if you want to [talk], of course.”

“People want the card,” Marco Rodriguez tells me in Spanish. “It’s good.” Not great, not life-changing. But he did use it to open several bank accounts. However, many people, he tells me, cannot apply for the card, because they do not receive utility bills in their name. That makes providing proof of residence difficult.

Lugo points to a couple other people as they walk in, repeating his question, and each man pulls out his card from his wallet and extends it toward me, so I can see. I know what the cards look like from photos, so I am not sure what more I am supposed to find printed on the white surfaces. It is simply a moment of proof, of providing the identification that was asked for.

The meeting’s agenda includes the dispute over underpaid, undocumented workers at Gourmet Heaven and the cases of several residents who were arrested by ICE. As Lugo attempts to rally people for a protest in the following weeks, he tries to convince a woman in the back that one does not need to be documented to participate. But after her own experience being detained, she is afraid to take such a risk: “I haven’t gotten over the trauma,” she says.

Looking back at the 2007 raids, New Haven’s most public round of deportation, it is clear that ICE cannot round up the undocumented without proper warrants for arrest. But it can entangle people in years of legal battles, with the threat of extradition constantly hanging over their heads. Of the twenty immigrants represented by the Yale Law School’s Jerome N. Frank Legal Services Organization after the raid, all were released except two, and the rest decided to either voluntarily leave the U.S. or to seek outside counsel, according to Wishnie. When eleven were awarded compensation of $350,000 in 2012, the Yale Law School reported that it was the “largest monetary settlement ever paid by the United States in a suit over residential immigration raids, and the first to include both compensation and immigration relief.” However, not everyone is so lucky, and no amount of money can take away the anxiety that the woman at the meeting—and thousands like her—live with daily.

This fear lies at the core of the Elm City ID’s struggles. Even when official policies change, people’s attitudes might not. The ID card arrived soon after another victory for immigrant groups; in 2006, the local police department ruled that officers cannot ask about witnesses’ or victims’ immigration status. This measure was intended to encourage undocumented residents to report crime; previously, if they gave their name to the police, they ran the risk of being matched to ICE’s national database. New Haven police followed officials in several other cities in declaring that their role was not to enforce federal law, but to keep the city safe. Last year, Connecticut as a whole took another step toward curtailing ICE’s powers by becoming the second state to sign the TRUST Act, promising not to detain immigrants unless they are convicted of serious crimes.

Still, a 2012 report by JUNTA and the Transnational Development Clinic at the Yale Law School stated that there is still “widespread suspicion” among Fair Haven residents about the resident ID card. Rumors persist, the report noted, that the card is solely for people who did not have papers or that federal officials will use it to detain undocumented workers. Okafor, the Community Services Administrator, says that until her staff starts meeting with focus groups and conducting interviews in September, they cannot know the community’s current attitudes toward the card. Anecdotes are, for now, the only evidence.

The card hopes to make residents feel safer in their community, but after past run-ins with the local police, some residents remain wary. After the meeting, Abel Sanchez, who has lived in New Haven for fourteen years, tells me that a policeman stopped him three years ago while driving—“I knew it was racist,” he says—and did not accept the card. It is useful as an identification document when dealing with the city’s trash collection services, he adds. But he doesn’t have much more to say about it, and he knows of only a few friends who have one.

Domingo Lopez, who has lived in New Haven for twenty-two years, tells me the ID is important here. He uses it at businesses and hospitals, and he has even opened a bank account. But he has also had problems with the police, even during the time he has had the card: “They see that you’re Latino, and they bad-mouth you,” he says. However, when I ask him for more details, he tells me that his last problem with a policeman was five years ago.

Latrina Kelly-James, the deputy director for Development & Programs at JUNTA, says the people she works with understand that ICE and local police operate independently, and that the municipal ID has helped give residents a sense of pride in New Haven. “The card makes them feel part of the city and makes them feel civically engaged,” she says.

However, the card is ineffective beyond city limits, where they may face other threats. In 2010, after being sued by residents, the city of East Haven was found guilty of repeatedly harassing Latinos. The city paid a $450,000 settlement in June 2014, but residents are still uneasy outside New Haven.

“When you have a welcoming city and two blocks down, you have a fear of being deported, that sense of fear is always going to be there,” Kelly-James notes.

Back in the People’s Center, Lugo asks a man who was released after being detained for eight months to come speak at the front of the room. As the man tells it, he was on his way to buy a sandwich when the police stopped him and sent him to immigration services. Lugo pulls out a mailing envelope and, with a flourish, hands the man at the front of the room his own United States Employment Authorization Card. “You can get Social Security, and a driver’s license,” Lugo tells him, and the man looks genuinely moved as he holds the card in his hand, until someone shouts from the back, “You can pay taxes, too!” Lugo takes a photo of the man holding up the card as he poses at the front of the room.

Documentation is coveted in this community. Even though the national card is just a temporary work permit, it is prized. And it grants far more privileges than New Haven’s local ID ever will.

***

The Elm City ID can help holders accomplish everyday tasks, but it only works if city organizations and companies accept it. Liberty Bank and Start Community Bank, both local banks, accept the card as a primary form of identification from people who wish to open a bank account. But, despite DeStefano’s early efforts, many of the city’s largest banks do not.

TD Bank, People’s United Bank, and Webster Bank do not accept the card as identification when opening an account. Webster spokesperson Sarah Barr said the bank is limited in the types of identification it can use, because it is a national bank that requires permission from federal regulators.

An employee at Citizens Bank who asks to remain anonymous tells me that residents come in once or twice a month requesting to open an account with the municipal ID. “I wish I could take it. I get so many people who come in and that’s all they’ve got,” he says, but a manager explains that the bank’s policy is based on “government-issued IDs”—and apparently New Haven’s does not make the cut.

Chase, Wells Fargo, and Sovereign Bank will take the card as a secondary form of ID. First Niagara spokesperson Karen Crane said the bank would also take it “on an exception basis,” when New Haven residents who are applying for banking services do not have other approved forms of identification and if the bank manager approves it. She cannot guarantee the same outcome in every case.

The murkiness of banks’ policies leads to confusion among residents and means that fewer of them end up opening accounts. According to the 2012 JUNTA report, residents in the organization’s focus groups were more likely to try to open accounts at big-name banks, which means that some may have been denied accounts simply for turning to the wrong bank. (Start Community Bank, for example, had had only 148 people open accounts using the Elm City Resident ID as of August of this year.) Only 48 percent of people surveyed reported having a bank account, and 27 percent stated that they used no financial services, including credit cards, prepaid cards, or check-cashing. Residents who could not open bank accounts because they lacked proper identification or because they didn’t understand the identification requirements were left without a safe, reliable way to manage their money.

Beyond the banks, only some local businesses accept the card as photo documentation. In a 2012 study titled “Documenting the Undocumented,” three Yale students concluded that Latinos were more likely than whites to be carded when paying with a check. However, stores were more likely to accept Ameracard—an unofficial ID, from a company based in Stamford that can be purchased online without proof of one’s identity—than the Elm City Resident ID. The problem, the researchers reported, was largely the municipal ID’s amateurish design and unofficial-sounding name.

If New Haven wants people to renew their ID cards, it will have to convince them that the card is a useful investment of time and money. At present, people lack information about its processing, and banks’ and businesses’ unwillingness to participate makes the card ineffective.

Luis Alberto Lopez, another New Haven resident, tells me that ten members of his extended family have the card, but it hasn’t helped them much. Bank of America turned it down when he attempted to open a bank account, and Walmart and Comcast refused to accept it as photo ID when he tried to make credit-card payments several years ago. A policeman in North Branford stopped a car he was a passenger in and asked about the ID, “Where did you get this one?” “As soon as I realized that nobody takes it, I realized that I better use my passport,” Lopez says, referring to his Mexican documentation.

Another immigrant couple Mallma introduces me to says that neither of them has the card, though they have been living in New Haven for eight years. The man tells me that the consular ID he uses marks him as a foreigner, so the Elm City ID would probably be good to have. But his wife states they did not have much information about it earlier, and now she cannot apply because her passport is expired. Their answers about the card are, in many ways, half-hearted; they alternate between lukewarm positivity and verbal shoulder-shrugging. After a prolonged conversation, the man concludes that there is no real difference between the municipal ID and the consular one: “I don’t get a better job if I have the card. It neither betters nor worsens life. It’s the same.”

***

The municipal ID has certainly helped some New Haven residents, but with mediocre reviews and little current publicity, current residents may not hear about the benefits in the years to come. And the 2014 changeover in the city’s administration introduced a new set of officials who were not around for the extensive community discussions that led to the creation of the card. Though Laurence Grotheer, the new mayor’s communications director, tells me that the city is still considering adding a debit function to the card, he adds that there is no real timetable for such a change. Instead, he points to another city project, the Shop•Dine•Park gift card, released in January 2014, which can be loaded with money to serve as a debit card at parking meters or to make purchases at more than two hundred participating local businesses—as the flagship ID card never could.

The municipal ID has certainly helped some New Haven residents, but with mediocre reviews and little current publicity, current residents may not hear about the benefits in the years to come. And the 2014 changeover in the city’s administration introduced a new set of officials who were not around for the extensive community discussions that led to the creation of the card. Though Laurence Grotheer, the new mayor’s communications director, tells me that the city is still considering adding a debit function to the card, he adds that there is no real timetable for such a change. Instead, he points to another city project, the Shop•Dine•Park gift card, released in January 2014, which can be loaded with money to serve as a debit card at parking meters or to make purchases at more than two hundred participating local businesses—as the flagship ID card never could.

At present, seemingly more legitimate forms of identification also threaten the success of the New Haven card. Starting in 2015, undocumented immigrants will be able to obtain Connecticut drivers’ licenses, though they will be marked “for driving purposes only” on the back and will have to be renewed every three years.

Emily Tucker, an attorney for immigrant rights and racial justice at the Brooklyn-based Center for Popular Democracy, says that New Haven’s work still serves as a model for the rest of the country, where municipal ID’s are the focus of many people’s efforts. The center has been one of the groups instrumental in developing the legislation in New York, after conducting a comprehensive review of the nation’s municipal ID card programs. “New Haven was at the forefront, so all of the lessons learned from that campaign, we knew they were going to come up for us too,” she says. But they also took into account the card’s shortcomings.

Theoretically, a municipal ID could offer even more advantages than a DMV-issued card or a Shop•Dine•Park card. Where the city has failed—in getting an official-looking design and offering discounts to card users—cities such as San Francisco and Oakland have succeeded.

In New York City, where the undocumented population consists of about 500,000 people, some of the key concerns raised at the start of the Elm City ID program and those in other cities are being revisited on a larger scale. Questions remain about why New York City will keep copies of applicants’ documents—such as pay stubs or children’s educational records—for at least two years. The New York Civil Liberties Union refused to support the legislation because of concerns that the police department, FBI, or Department of Homeland Security could force the city to turn over the records without probable cause.

There is still a vocal group of Americans opposed to measures that are so openly supportive of immigrant groups, and these voices exacerbate the worries of the population now gingerly approaching new forms of identification. William Gheen, the president of the Americans for Legal Immigration PAC, states that New Haven is still a sign of the federal government’s terrible willingness to turn a blind eye to the “illegals” in the country. When the card was first released, his group distributed bilingual pamphlets in forty states with the instructions: “Come to New Haven CT for sanctuary. Bring your friends and family members quickly.” His opinion has changed little since 2007, when anti-immigrant groups such as the Yankee Patriot Association, Southern Connecticut Citizens for Immigration Reform, and the Community Watchdog Project protested against the card. “It sends a clear message to encourage illegal aliens to enter the United States,” he says.

***

DeStefano, the former mayor, is not blind to the city’s failure to build a complete support structure for the immigrant population. But he slips out of the precision of policy makers into the language of an idealist when I ask why he still believes that the country will come to embrace its immigrants: “There is an American identity that does value freedom and does respect hard work and does value choice and does respect decency,” he says.

Even if New Haven’s municipal ID card still needs some work to be effectively integrated into the political, social, and economic life of the city, it outlined a process to help residents considered “illegal,” allowing other cities to learn from the Elm City’s successes and missteps.

Okafor, of the Community Services Administration, says expects to see Toni Harp’s tenure as mayor to bring greater collaboration with banks, as per the card’s original goals. The summer has brought the early stages of planning, as she attempts to assess the barriers still in place for undocumented residents who have not managed to open accounts. In the meantime, many are still in economic limbo.

Idealists brought the card to New Haven, but it remains to be seen whether the idea can stay alive—and whether programs like it are the right answer for America’s undocumented. “We strive for perfection. We do not always accomplish perfection,” DeStefano adds, before he leaves for work.

Maya Averbuch is a junior in Berkeley College. She is the managing editor of the New Journal.