“What is a museum guard to do, I thought to myself; what, really, is a museum guard? On the one hand, you are a member of a security force charged with protecting priceless materials from the crazed or kids or the slow erosive force of camera flashes; on the other hand you are a dweller among supposed triumphs of the spirit.”

— From Leaving the Atocha Station, Ben Lerner

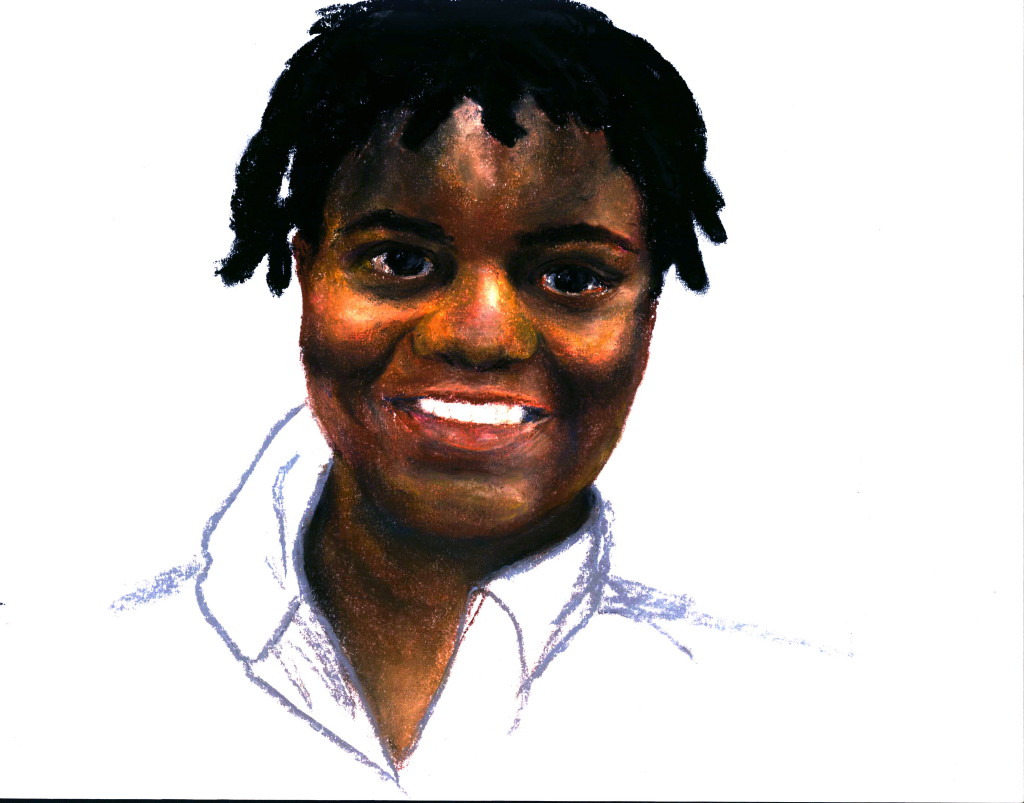

It’s noon, and Imani Lane looks over forty-seven tiny security screens spread across two PC monitors. Lane has been a guard at the Yale University Art Gallery for more than thirteen years. After years on the floor, she now also works at the front desk in the Nolen Center, the museum education building across the street from the Gallery. She scans the screens for movements the on-floor guides might miss. When visitors walk through the galleries, sit on benches, or encounter a Van Gogh for the first time, Lane is watching.

As a guard, especially when in the gallery, Lane is tasked with helping patrons. But, mostly, her job is not to get in the way. “We’re supposed to be invisible,” she says. It’s difficult to imagine Lane, who is bubbly and effusive, fading into the background. Lane laughs often when she talks. She is at ease in her black leather office chair, wearing a uniform of a blue button-up shirt, khakis, and clogs. But she emphasizes that the role of a guard is to maintain order, not to “to bother or talk too much to people in the gallery.”

When visitors walk through the galleries, sit on benches, or encounter a Van Gogh for the first time, Lane is watching.

It can be tough not to talk, especially when patrons want to address Lane. “When you’re in an art gallery, you can get emotional,” Lane says, and visitors sometimes look to her to unload their reflections. Van Gogh’s Night Café, in particular, often moves people to talk. Lane just listens and nods politely. When people ask if she likes the art, she can’t share her opinions. But, at her desk away from the art, Lane makes it clear that her natural impulse would be to engage enthusiastically with visitors.

A few minutes into our conversation, a museum patron wanders out of the elevator near Lane’s desk, looking lost. Interrupting herself mid-sentence, Lane greets him, “Hi, how are you doing? Welcome to the Nolen Center. Are you looking for the way out?” The man responds yes, revealing his French accent. Immediately, Lane asks, “Parlez-vous Français?” and, when he nods, she adds, “Je m’appelle Imani.” He grins and asks if she speaks Spanish, too. Lane replies, “un pocito,” before laughing and giving him directions to the exit (in English).

Sending the tourist off in the elevator, Lane modestly shrugs. “You meet so many people from around the world, you want to be able to say something.”

Lane stands still as her well-practiced gaze cuts easily to the center of the painting, to the knife in the figure’s hands. She focuses on the slits and angles on the canvas; they remind her of the flipbooks she used to make in art class as a kid.

When there aren’t visitors in the galleries she’s guarding, Lane switches from being a guard—watching people watching art—into being a patron of the museum. She fixes her gaze on her favorite pieces, focusing on one or two at a time. “I love objects that look like they’re in motion,” she says.

When I meet Lane again, this time in the lobby of the Yale University Art Gallery, we take the elevator up to the Modern and Contemporary section to visit The Knife Grinder, one of Lane’s favorite paintings. In it, a man hunched over a knife pushes through geometric shapes. It’s a cubo-figurist piece. Shapes radiate outward from the central figure as multiple iterations of each of his body parts repeat in shades of orange, blue, and grey.

Lane stands still as her well-practiced gaze cuts easily to the center of the painting, to the knife in the figure’s hands. She focuses on the slits and angles on the canvas; they remind her of the flipbooks she used to make in art class as a kid. “The more you look at it, the more you notice the movement of the knife,” Lane notes. Then she starts to recount the progression of her relationship to this work: at first she was puzzled by the knife, since when she looks at a painting for the first time, she never reads the labels. (She waits until she has explored the painting on her own.) “For a while when I first saw it I was like ‘is that a fork?’” She told herself, “Let me figure it out.” So she asked questions. Where is the figure standing? Is he in a basement? Is he using the knife to create or destroy? She muses, “Sometimes I don’t want to know too much because that wouldn’t leave as much for me to do on my own.”

Looking closely, Lane cycles slowly through the museum’s collection, interpreting and re-interpreting. But then, as soon as a visitor walks in, she snaps to attention. She needs to make sure that the art is out of harm’s way.

The Gallery holds pieces by Picasso, Brancusi, Rothko, and Fra Angelico, to name a few. But, for most of her day, Lane is not focusing her gaze on brushstrokes. Instead, she says, “I make sure no little children are crawling on the floor crying that they lost their mommies” and “I’m just here to make sure the art stays on the walls.” She scans the corners of the room in case someone trips on a bench. From her perch at her security desk, she focuses more on the moving shapes of visitors than the tiny, static art on the gallery walls. She is constantly watching to make sure no one gets too close to the art. “Everyone has the urge to touch,” she says.

She envisions a “touch gallery” with touchable copies of famous pieces. Instead of discouraging tactile engagement, this space would sanctify it.

Leaning in, as if telling me a secret, Lane describes her dream exhibit: the full a tactile museum space. She envisions a “touch gallery” with touchable copies of famous pieces. Instead of discouraging tactile engagement, this space would sanctify it. She pictures a space filled with reproductions of the museum’s greatest hits. She has a specific room in mind, one in the basement of the YUAG that has an empty wall. Visitors (and Lane) could view pieces that, she says, for example, will “Feel and look just like an actual Picasso. And you can touch it.”

There would still be guards in this gallery, to help out if someone trips or if a kid wanders in unaccompanied. But the works would not need to be watched so vigilantly. This dream space would make Lane’s life as a guard easier. In this touch gallery, she imagines, “people can hopefully get the touchies out of them,” so upstairs they would not try to touch original works. Lane prefers when she does not need to stop visitors from doing what they want to do. When visitors come in, she says she always thinks, “I don’t want to talk to you,” hoping that the patron will not cause trouble.

Lane develops all kinds of plans while in the gallery, and she acts on some. After hours looking at Picassos, she had the idea to start sketching famous Picasso paintings “from a security guard’s perspective” in her free time. She just ordered some fabrics on eBay to start sewing dresses inspired by patterns in paintings. “All these ideas come from me working here, me being around the art handling, the exhibitions department, conservation,” she says.

The museum guard does a delicate dance—protecting art while trying not to interfere with the onlooker’s experience. In the tactile gallery of Lane’s imagination, this task might be easier. But for the moment, she continues to guard the space, eyes flickering across the canvases or computer screens, absorbing all the angles.