Observant Jews in New Haven distill beauty and closeness from socially distanced religious practices.

At 10 a.m. on the Fourth of July, Esther Nash arrived at the parking lot of Congregation Beth El–Keser Israel in the Westville neighborhood of New Haven for Shabbat service. For three weeks, with new COVID-19 cases declining throughout the state, the synagogue at Harrison Street had been able to hold services in-person, albeit outdoors.

That day, the summer sun was high in the faultless blue sky. Nash carried a leather-padded brown folding chair from a cart, which the synagogue staff had wheeled out earlier that morning, and took a seat in the shade of a large sugar maple tree.

People sat dispersed across the parking lot in twos, threes, or fours, half their faces concealed behind masks. At the reader’s table, the Rabbi’s teenaged son, Noam Benson-Tilsen, was chanting from the Torah. As he chanted, letters became words, words became song, and the sonorous melody flowed through the listeners’ ears. Congregants bowed as they prayed, rocking their knees, the red bound book of scripture and smaller blue book of prayers clasped in their arms. Before the pandemic, the synagogue’s Rabbi, Jon-Jay Tilsen, led services in the synagogue’s sanctuary. His voice would reverberate off the laminated wood panelling and fill the high-ceilinged, sunlit space. But now, for the 35 people present to gather in the sanctuary together, breathing the same air, would be a health and safety risk.

Outdoors, Benson-Tilsen’s voice was muted by the wind, dissipated into a low call. From twenty feet away, he sounded as though he was standing behind a thin wall.

“God now wants us to sing quietly,” Nash said afterward. She was reminded of the prophet Elijah, who was sent fleeing South from Queen Jezebel through the wilderness of Judah for defending the Hebrew God against the prophets of Baal. Through mountain-splitting winds, rock-shattering earthquakes, and vicious fires, he did not see God. He did not hear Him. Then, in the silent aftermath of the blaze, he heard the “still, small voice” of God address him. That morning, in the synagogue parking lot, Nash thought now was the time to listen to the still, small voice of God.

When he was finished, Noam returned the Torah scroll into its blue velvet cover and carried it to the holy ark of law, an ornamental chamber which houses the scroll. Before the pandemic, a procession of five or six people would carry the scroll counterclockwise through the sanctuary. The act is symbolic of “bringing the law to the people,” Tilsen explained. That day and during every outdoor Shabbat service so far, however, the task belonged to the Rabbi’s son alone.

When the pandemic prompted many religious groups to convene online, with Zoom worship sessions and Friday prayer live streamed on Facebook, the same transition could not be applied in certain Jewish communities.

Orthodox Jews, who adhere most strictly to Jewish law, refrain from using electronics during the Sabbath because it is prohibited by Jewish law on the day of rest, along with thirty-eight other activities. Some members of the Conservative Jewish movement, which believes that Jewish law, while binding, should evolve historically, also do so.

Many of the Congregation Beth El-Keser Israel’s members, including Tilsen’s own family, fall into this category. The reasons Tilsen offered for avoiding technology on the Sabbath are varied: it is a religious commitment, a way of being a good Jew, and a personal way of serving God.

And so, when the synagogue closed for the first time in its 128-year history on March 16th to help contain the spread of the deadly coronavirus, Rabbi Tilsen did not hold Shabbat services online. “If you’re going to do all these things, then it removes the beauty that we created by adhering to constraints,” he said.

In the pandemic world, some things can be moved to Zoom—calling into a wedding, practicing daily prayer, and singing songs together during the Seder, or the ritual feast that marks the beginning of the Jewish holiday of Passover. Many others cannot—hugging a loved one, holding Shabbat service in observant Jewish communities, and, depending on who you ask, forming a minyan, which is an assembly of any ten Jewish adults (in the Orthodox tradition, specifically men). A minyan is required before certain religious rituals can be performed, including reading from the Torah and reciting important prayers like the Kedusha and Kaddish.

The Rabbinic definition of a minyan is unequivocal: the ten adults need to be physically present in the same space for the group to constitute a quorum, explained Tilsen. “So a group that is connected only by being ‘on-line’ by Zoom or phone does not constitute a quorum,” he said. That said, many reform and modern synagogues are holding full services, including Torah reading and Shabbat services, on Zoom.

Rabbi Fred Hyman, who leads the Orthodox Westville shul in New Haven, said, “The Kedusha and Kaddish is a very meaningful part of the service, and we still don’t allow it [to occur online]. We don’t just follow an emotional response. That’s how strict we are, and I think the virtual minyan is misplaced.”

In 1999, Rabbi Maurice Lamm warned presciently of a “crisis” in the introduction to a reprint of his 1969 seminal textbook on deathcare, The Jewish Way in Death and Mourning, that would pressure Jewish people to succumb to “commercial,” “American,” non-Jewish ways. “The crisis will come, ready or not,” he wrote.

The Covid-19 pandemic appears to be one such “crisis.” The story of religious Jewish communities during the pandemic has been one of finding beauty in constraint. There has been more continuity, rather than change, in their practice of Judaism even as stores are shuttered, synagogues are closed, and people are quarantined.

The dozen Jewish people interviewed for this article explained how they have adapted, resumed, and in some cases, coped without the rites of birth, life, and death that generations before them practiced according to Jewish law. Seven of them referenced the specter of the Holocaust and enduring anti-Semitic hate in the United States and Europe as something that informs their understanding of the pandemic’s impact on the practice of Judaism.

Andy Sarkany, an 84-year-old Westville resident and Holocaust survivor, does not think the pandemic has changed his Jewish faith at all. He was a child in the seventh district of Budapest during the Holocaust and could not openly observe religious practices at that time. And when he was a teenager in Soviet-occupied Hungary, religious observance was practically forbidden. His mother still lit candles at home every Sabbath.

Now, every Friday night since the pandemic began, Sarkany’s wife Aniko lights candles at home. He recites the Kiddush, a blessing said over wine or grape juice to sanctify the Sabbath, reads from his prayer books, and does individual prayer at home. Although social distancing has reduced many Jewish practices to private worship at home, Sarkany does not think it matters.

“When you have a certain level of belief, the environment around you will not affect that belief,” he said.

1. Birth

Rachel Somerstein’s baby, Jonathan, had fallen asleep on the dining room table even before the brit milah began. His mother guessed that it was the sugar water-tylenol mixture that the mohel had given him, but newborns sleep a lot, and Jonathan was only ten days old. Soon, the circumcision ceremony would take place, welcoming him into the covenant of Abraham and to his family. It was the ideal situation: Emily Blake, his mohel, said with a laugh that her definition of a “perfect bris” is one where the baby doesn’t cry but where the parents are moved to tears.

Jonathan’s father nearly passed out as he observed the procedure. The mohel placed a Gomco clamp, shaped like a steel bell, on the baby’s penis. It would protect the head of the penis during the procedure and limit blood flow to a minimum. Blake took a scalpel and cut straight along the foreskin, easy and simple. It is a ritual of blood, one that Blake strives to make as painless as possible.

Jonathan is an easygoing baby. It took him a few moments to cry when he was first delivered from the warm womb into a hospital room. Giving birth during a pandemic wasn’t easy, said his mother. The virus was ravaging her home state of New York and she worried that she may have to give birth alone. As Jonathan kicked inside her, more than 100,000 people around the country died from COVID-19.

But as soon as she found out she was having a boy, Somerstein knew she had to have a bris, a circumcision ceremony done according to Jewish law and with kavanah, which refers to a mindset of sincere intentionality that must accompany Jewish rituals. Although her husband is not Jewish and has not yet converted, the couple keeps a kosher home, practices Shabbat, and says the Shema prayer with their daughter before she goes to sleep each night.

Somerstein had envisioned renting a place downtown in their small village of 14,000, nestled by the Shawangunk Mountains in the Hudson Valley, and inviting all their siblings, parents, and close friends. But because of the pandemic, the guest list dwindled to just five: Jonathan’s mom, dad, sister, and grandparents.

“At one point I felt so sad about it,” she said while watching over her son and 4-year-old daughter. “It’s so sad that we couldn’t introduce our son to our families the way we wanted to.”

But having a brit milah was important to Somerstein. She wanted to give her son the freedom to decide how he wanted to practice Judaism when he grew older and this was a way to give him that agency, she said. Jewish men who do not have a bris done by a mohel with the proper blessings, in the proper time frame (not before—and ideally on—the eighth day of life), or with the proper intention, must have a ritual drop of blood taken from their penis to make the circumcision “kosher,” as Blake calls it.

The baby’s grandparents, father, older sister, and mother, said prayers over him. One of the blessings they recited was the birkat hagomel, spoken after someone has survived a dangerous journey—in this case, childbirth.

Four years earlier, Somerstein had survived a C-section for her daughter without anaesthesia. This time, she had gone into prodromal labor five days days before Jonathan was born. She was dilating and having contractions, her body was preparing for a baby that was coming but not ready yet. Jonathan was finally born at 9:17 p.m. on a Tuesday, with big cornflower blue eyes and pudgy legs. In early August, Jonathan was just over a month old, “figuring out who he is as he figures out the world around him,” says his mother.

During the bris, after they said the prayers, they gave Jonathan his Hebrew name—Yonatan. It was the name by which he would be called to the Torah, his covenantal name. On a laptop screen, Jonathan’s aunts, uncles, and grandparents said blessings. They each drank grape juice and wine, in lieu of a celebratory meal that could no longer be held in person.

Now that many brises have to be celebrated over Zoom, Emily Blake, Somerstein’s 64-year-old veteran mohel who has dedicated more than three decades of her life to this work, likes to begin the ceremony with a pun: they’re doing this “chai-tech” (“chai” means life in Hebrew).

“We are accepting things we never thought we’d have to live with, in this pandemic,” said Blake on the phone one morning as she drove from New York to New Haven for a bris. “I think people are just so happy they’re getting a joyous moment to celebrate, that there’s this new baby coming into their family. It’s a moment that you can step out of the incredible sadness of being stuck in lockdown, to have the sunshine break through that dark cloud.”

2. Survival

As a child growing up in the Jewish neighborhood of Borough Park in Brooklyn, New York during the 1950s and 60s, Esther Nash carried with her a message, forged by her parents’ experiences as Holocaust survivors, that the world is not a safe place. Her mother, Eva, had been plucked from her rural town in the Hasidic belt of Transylvania, Romania and deported to Auschwitz in the spring of 1944. She was trapped there when the camp was at capacity and eventually was moved to work as a slave laborer at a Krupps munitions plant, where she worked on an assembly line making grenades.

Eva would later tell her daughter about how on Yom Kippur, the Nazi guards in the concentration camp would deliberately offer more rations throughout the day of fasting, “to let the Jews know they no longer had a religion, no longer had a culture, no longer had a life,” said Nash. But Eva always fasted on Yom Kippur even though she was near starvation. In the spring of 1945, the Russians liberated her and other Jewish prisoners.

In 1948, Eva, then a 24-year-old Hasidic Jewish survivor of Auschwitz with shoulder-length dark hair and a shy smile, found herself in a displaced persons’ camp in Pocking, Germany. Her own parents had been gassed immediately on arrival in Auschwitz.

At the displaced persons’ camp, she met a fair-haired young man named Chaya Rosenberg who was four years her senior. He was almost six foot one and Eva found him very good-looking. One Friday evening, she walked into his family’s room as they were preparing for the Sabbath. Years later, Eva told Esther that they were celebrating it in much the same way they did in her own home: a white tablecloth laid out, lighted candles, prayers recited. When Eva saw that Chaya had a home, parents, and a family, and was revelling in the “beauty of the Sabbath,” she knew she wanted to marry this man.

the Pocking displaced persons camp in 1948.

Three weeks later, they were married during an “epidemic of marriages” in displaced persons’ camps all over Europe immediately after the war. Nash said that people were trying to recreate the family they had lost. Eva wore a white wedding dress with long peasant sleeves and deep skirt folds that were circulated among many brides in her displaced persons’ camp. The rings were secondhand. Chaya’s was engraved with somebody else’s name: Linda, inscribed with the date “07.01.37.”

Their wedding photo was taken in black-and-white in an area of the camp that the refugees called “Cafe Tel Aviv,” where weddings were held. Fir trees decorated the backdrop. There was no bouquet, so Eva held potted flowers.

“My parents were traumatized people,” said Nash, as she looked at the photograph, now colorized and digitized on her computer. “There was always the message that it was dangerous to be a Jew, but you should never, can never, give it up. It’s part of your identity and existence.”

Her parents arrived at Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy Airport) in June 1949, carrying with them their Yiddish tongue, the trauma of the Holocaust, and their 3-month-old daughter Esther. Her father spoke no English. By then he had long been accustomed to working on the Sabbath because he had done so while working as slave laborer in a special settlement near Novosibirsk, Siberia, and then on a kolkhoz in Tajikistan during the war. When he arrived in New York, he continued to work on the Sabbath because he needed to make money. But every Sabbath, he would recite Kiddush over challah and wine in a silver Kiddush cup. On holidays and festivals he attended the synagogue across the street with his family.

For the first three years of her life, Nash only spoke Yiddish, the common language used at home, with her Romanian mother and Polish father. Every Friday night, her mother would prepare a Sabbath meal—challah, gefilte fish, chicken noodle soup, roast chicken, and sometimes stuffed cabbage. Eva would light a candelabra with glowing Sabbath candles and recite blessings. But there were many things her mother kept to herself—what happened in Auschwitz, what she had seen, what she had survived. “More was revealed in her inability to speak about it,” said Nash.

When the coronavirus began infecting scores of people worldwide earlier this year, Nash was not at all surprised, owing to her years of professional experience as a physician. But she had also grown up with the heavy lesson, first borne by her parents, that had prepared her for this.

“The pandemic showed that there was a chance the world could change in a heartbeat because it did for my parents,” she said one afternoon in July. “You wanted to know about how other such difficult times adapted Judaism—I would say it’s the reverse. Judaism allowed us to adapt to whatever times we found ourselves in because of the values, because of what it tells us about humanity, about people, about the tenuousness of life, and the important things.”

***

Three-year-old Ruthie Frosh loved to sit with her grandmother in the front row of the synagogue’s balcony, overlooking the central nave, in Vienna’s sixth district. From that point, she could see everything—the beautiful neo-Gothic architecture, the colorful stained glass windows, and the oil paintings in the interior. She could see the ark, the lectern, and the Rabbi chanting from the Torah. On special Jewish holidays, her grandfather would carry her in his arms downstairs and bring her to the Torah scroll. It is her first memory and the one that she conjures today, as 89-year-old Ruth Weiner, and one that speaks to the strong sense of Jewish identity she had even at that young age.

She learned to read by age four, and by age five, she was reading the newspapers, finding out about “all kinds of stuff not appropriate to my age level.” When the Anchluss happened in 1938, she was seven years old. Germany and Austria had formed a union. Hitler and thousands of Nazis marched into Ruthie’s home city of Vienna and “the welcome could not have been more wholehearted or widespread or complete,” she said. Buildings were draped in red buntings with swastikas. In the streets, everybody was in uniform.

“On that day I stopped being a child,” said Weiner. It became clear to her that to be Jewish meant you could be arrested or shot in the street for no reason, or made to scrub the sidewalks until your hands were bloody. She had to learn how to make herself invisible.

One morning in first grade, a close friend came to school, looked at Ruthie, and spat on her. “She said, ‘You’re a Jew. I didn’t know you were a Jew,’” Weiner remembered. “That just slashed me to my core and made my new status very clear to me.”

In 1938, at first, young Jewish children could still attend public schools and receive Jewish religious education there. Ruthie learned Hebrew and prayers. Whenever Ruthie and her family went to the district’s elegant synagogue with its balcony and its bare-faced brick turrets, they were on guard. “There was a great sense of foreboding, you were prepared for something bad to happen at any point,” she said. Months later, during Kristallnacht, a brutal two-day pogrom targeting Jews, the Schmalzhoftempel synagogue would be burned to the ground.

Weiner explained that Judaism is a very portable religion, a characteristic that would become important later when she fled Vienna to England as a refugee child in the kindertransport, a rescue effort that transported 10,000 children from Nazi-occupied territories to safety just ahead of the war.

“Being Jewish goes beyond religious practice,” said Weiner. “Judaism is both a body of ceremonial practices, either in the home or in the synagogue, and equally a practice of everyday values, of how you see yourself in terms of what you expect of yourself, in terms of your own character, and more importantly, how you interact with your community at large.”

On November 10, 1938, the day that would become known as Kristallnacht, Ruthie took two streetcars and walked four blocks to school in the Jewish quarter with her best friend, as she had done each day for months. Something was seriously wrong. Jews were huddled in streets filled with broken glass and crowds of people were throwing rocks. At 10 a.m., the teachers dismissed them out of a side door, ordering them to hold hands. If you see a group of more than two Nazis, cross the street, they told her. Stores were looted. Fires were burning in the street. That day, more than 91 Jews were murdered. All but one of Vienna’s synagogues were incinerated.

When Ruthie arrived home, her mother was waiting for her. By then, her father had been imprisoned for a month because of “political crimes.” A non-Jewish Nazi lawyer who was her father’s friend had protected him from being sent to a concentration camp.

Her mother rushed her into the house, past two Gestapo officers standing outside. Five minutes later, they heard an “unbelievable banging” on the door. Her mother made a motion for Ruthie to remain silent.

For seven hours, they stayed seated in one spot, not making a sound, unable to eat or drink or use the bathroom. Every half hour, the telephone would ring. Ruthie’s mother was terrified, but remained silent: Was it a trick? Was it somebody in the family calling for help? She did not know what to do.

By 9:30 p.m., the intervals between the pounding had grown longer. The phone rang and her mother finally picked up. The voice on the other end told her not to say a word. It told her to dress herself and the child. If she heard three taps on the door, it meant the Gestapo had left and they could come out. It was the lawyer who had protected her father and was now rescuing them. That night, Ruthie shared a bed with the lawyer’s daughter, in his house.

Over the next few months, Ruthie’s mother worked on finding a way for them to gain entry into the United States. She managed to contact very distant family members—descendants of cousins of Ruthie’s grandfather—who lived in Texas. They banded together and issued an affidavit, promising to take on the responsibility for financially supporting Ruth and her parents, should they come to the U.S.

Eighty-two years later, Weiner sat on an old sofa at her home in Bloomfield, Connecticut. Even at her age, she still has a twinkle in her eye and an exuberant energy in her voice. After all that she has witnessed, she said she still believes in God but that “I’m sometimes quite angry with him.” She has lived through periods of deprivation and rationing, learned how to make cake out of sweet potatoes for Shabbat when she had nothing else to use, and shared the last of her sugar with a neighbor because “that was just the thing to do.” In light of her experiences, she said that the inconvenience of the pandemic can be dealt with. “This is nothing compared to that.”

But she added, “I feel for people who are alone or are not in comfortable housing. I feel for the people who are experiencing illness or loss or deprivation, or who’ve lost their job.” She said that people reveal who they really are in times of crisis, pointing out that during the pandemic, some people truly rise to the occasion, such as her neighbors who offered to deliver groceries to her. Yet others refuse to wear masks, and some big businesses take advantage of economic relief loans yet fire their employees.

“It is incumbent upon us to care for each other,” said Weiner. “This goes back to how the Jewish religion operates in times of crisis.”

3. Death

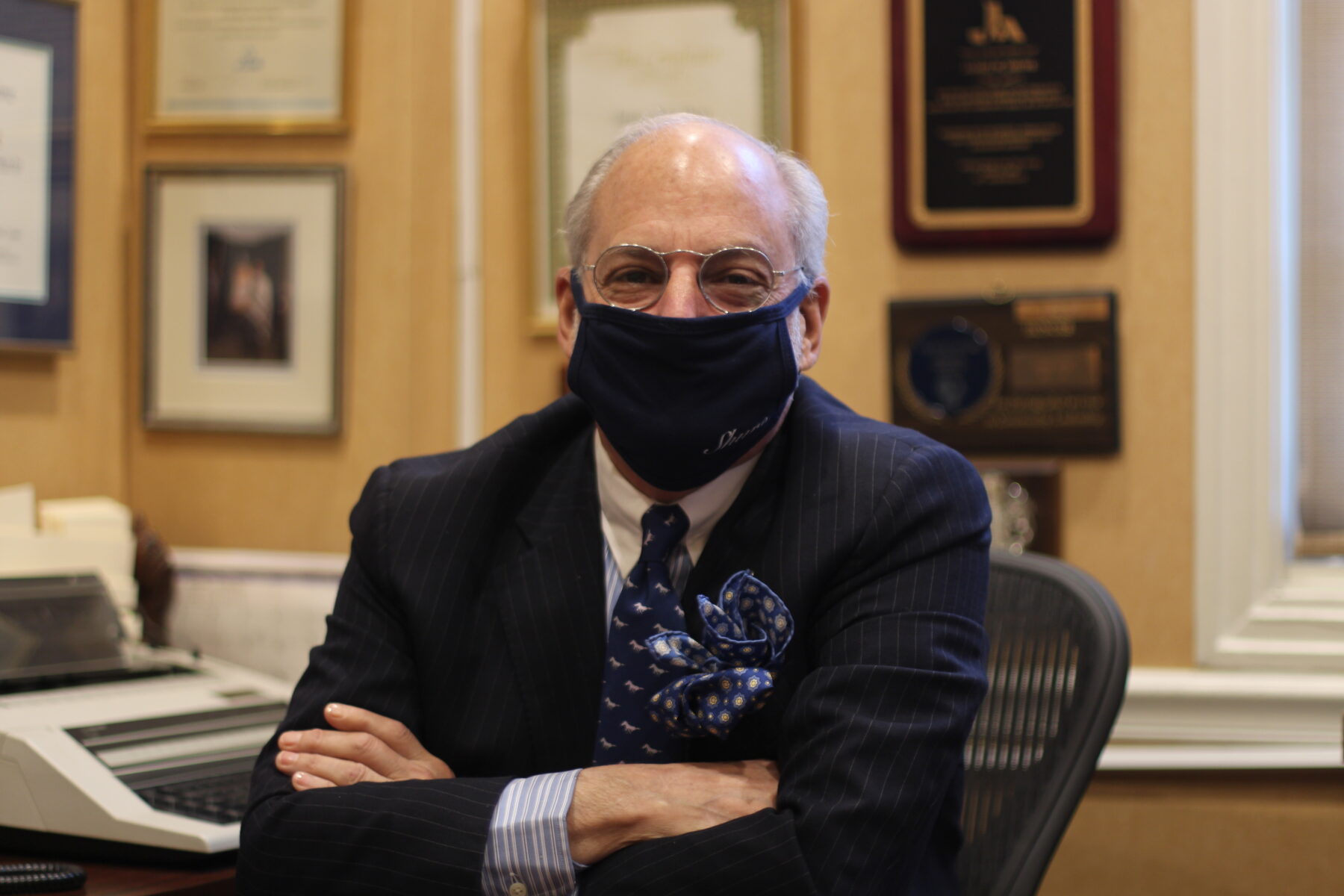

“Everything that is done in a Jewish funeral stems from the word respect,” said James Shure, a Jewish funeral director who works out of a Dixwell neighborhood funeral home founded by his father. You do not let a person die alone. You light a candle near their head. In the pandemic, many family members could not enter hospitals to visit their Covid-infected family members, let alone sit by their side as they died.

Each member of the chevra kadisha, translated “holy society”, looks more like a surgeon than practitioner of Jewish law when they enter the room at the George Street funeral home. They are volunteers who give their time and energy to do the tahara, or the sacred washing of a dead body, which is intended to return a person departing this world to the same pure, clean state they were in when they entered it as an infant. They wear face shields, masks, goggles, gowns and double-layered gloves. It is one of the greatest mitzvot, or good deeds, a Jew can perform. In the pandemic, the deed is even greater.

“These people put themselves at risk without batting an eye,” said Shure.

After death, the body of a person who died from coronavirus might still be contagious, although scientific literature on post-mortem contagion is still nascent. Since the outbreak of the virus, the shomer, who watches over the dead body, has to stand at least 20 feet away from the body in Shure’s funeral home.

As soon as the pandemic was declared, it took only two phone calls—one to California and one to New York—for Shure to determine how to carry out the tahara in a way that protects the people who are doing it while respecting the ritual and the dead person. The duration of the washing was halved. Instead of leaving an infected body on the washing table, they would be carried directly into the casket. But all the prayers are still said—prayers for forgiveness and prayers for eternal peace.

Jewish burial law requires that the casket be lowered into the earth and covered with soil. They recite the Tziduk Hadin, a prayer, right after the grave is filled. They chant the El Malei Rachamim, asking for rest for the person’s soul. It is a moment of reckoning with the finality of death, Shure said. “It somewhat brings closure to the family to see the casket lowered and very often, that is when the family becomes rather emotional.”

Now, safety regulations mandate that Covid patients have to be lowered prior to the family’s arrival at the cemetery. “It’s not cathartic,” Shure said.

He has witnessed many funerals happen without those present being able to say the mourner’s Kaddish, an Aramaic prayer that is often said at Jewish funerals. To recite the kaddish, a minyan must be formed, something not always possible with the Connecticut state rule allowing no more than ten people at a gravesite.

“The kaddish does not mention death at all,” said Shure. “Rather, it installs and magnifies God’s name again as our world has fallen apart as we know it. We merely boldly, boldly, put our faith in God.”

“The repercussions of the disease did not stop at death. It absolutely affected, I think, the well-being of the mourner,” he said. “I do not believe to this day, and it’s sad, that [families] were able to at least begin their mourning in a meaningful way.”

***

Yaron Lew has known Shure for 21 years but has never needed to use Shure’s funeral home until now. Lew does not believe in God. He doesn’t believe in the afterlife. His wife, Liora, believed in God. She grew up with a very orthodox Jewish grandfather and an observant mother who emerged from the Auschwitz death camp believing that her survival was due to divine intervention (her father, after surviving the Dachau concentration camp, became an atheist). Lew grew up on a secular kibbutz, a collective community, in Israel.

Lew speaks with a commanding voice and laughs a lot, smile lines visible through his thin-framed glasses. Over the course of his 36–year relationship with Liora, he went from being a Jew who never went to synagogue to becoming the President of his local synagogue, BEKI. Lew met Liora underwater, beneath the Mediterranean shore, in an Israeli military submarine in the city of Haifa, where Lew was serving as a naval officer and where Liora had grown up.

Yaron Lew’s wife and his brother passed away within a week of each other in June this year. Lew was by his wife’s bedside when she passed, while his brother was in Israel. He had been sick for over two years; she had only been sick for two months. Neither of them passed from the coronavirus. He was buried according to Jewish law without a casket, so that his body may return to ash and dust in the earth. She was buried according to cemetery rules in a casket. Lew sat shiva, the seven days of mourning that commence upon burial, in his home, in person, to mourn his wife. He called his family on Zoom for a few hours a day as they sat shiva for his wife and then for his brother.

The cemetery told him a maximum of 30 people could attend, so 30 people gathered at the gravesite for the burial. Everyone who attended had to wear a mask, and the funeral home tried to live stream the funeral for those who could not be present. But that sweltering day, with the temperature in the high-80s, the equipment overheated and the live stream failed. Each person donned a pair of latex gloves to pick up a shovel and scatter dirt onto the casket. The act is symbolic of saying goodbye, said Lew.

At the shiva, Lew and his family used the outdoor deck and backyard of his Westville home to ensure the safety of the mourners. They didn’t kiss, they didn’t hug, they didn’t shake hands; he mourned within the constraints. Each day, more than the ten people required to have a minyan attended evening service so that they could say kaddish. They held a Zoom call for those who were unable or uncomfortable with travelling to Lew’s home for the shiva. Up to 50 people attended virtually, including his wife’s sister and Lew’s siblings, who live in Israel.

He found himself on the opposite side of the screen when he sat shiva for his brother. He could not travel to Israel for his funeral and shiva. When I asked him how it felt, Lew paused for a long time and sighed. “Very distant. Very difficult,” he said.

In mid-June, when Liora was hospitalized for the final time, the doctors called Lew. During her previous hospitalizations, Lew and their children were not allowed to visit due to COVID-19 regulations. He snuck packages of letters and chocolates, cookies and flowers, in for her—“so at least she could have the smell and taste of home.”

“They said, ‘It’s good news and bad news. The good news is we are letting you and your daughters into the hospital, the bad news is we only let relatives of terminal patients go into the hospital,’” Lew recalled. She was moved into a hospice room a week later. “I spent the whole last night with her, and then she passed away in the morning,” he said, eyes sparkling with tears behind his glasses.

I asked him what mourning means to him. “I talk about her a lot,” he said, smiling slightly. “I have pictures of her. I cry in the shower in the morning. I talk to her once in a while. I talk to friends about her. We talk with the girls about her, what she would think and what she would say. I’m not sure if that is remembering or if that is mourning.”

This April, two weeks before Liora was diagnosed with a rare and aggressive cancer, the Lew family celebrated the Passover Seder together. Instead of the usual 40 people gathered in a rented clubhouse, it was just Lew, Liora, and one of their daughters around the Seder table at home. Liora made chicken soup and butternut squash soup and brisket, Lew made gefilte fish (it was a three-day cooking event), and their friends delivered the sweet, sticky traditional Passover dish of haroset, homemade. The families were physically separated, but they were together––eating the same food, singing the same Passover songs, reciting the Haggadah. “Mah nishtanah, ha-laylah ha-zeh, mi-kol ha-leylot,” they sang. “Why is this night different from all the other nights?”

As a non-believer, Lew had always seen going to synagogue as a non-spiritual affair. But since the pandemic hit, Lew said he has started providing more spiritual support to the synagogue community. He writes to the congregation once a week. In those letters, he reminisces about returning to the kibbutz where he grew up, and how when he walks through the gates, he sings a song about how he is just a visitor in the landscape of his childhood. He writes about how he has felt a little like a visitor in the synagogue of late, and of how the pared-down Shabbat service in the parking lot was familiar. “It led me to reflect on the evolutionary road we travelled during these quarantine months,” he wrote in one letter. “We started to adapt and we reinvented ourselves.”

***

When Esther Nash’s father was on the frozen tundra in Siberia, freezing and close to death, he would pray to God that He should let him live. “I think he would have been very happy back then if he was told that he would live to ninety-two,” Nash told me on the phone on a sunny day in July. Both Eva and Shaya Rosenberg lived to be the same age. Until her last days in a nursing home, Eva always wore a gold Star of David, an engagement gift that Shaya had made by his brother-in-law.

Since the pandemic began, Nash has begun taking long walks through Woodbridge walking trails, and kayaking down the Housatonic River. “I think I’ve become more spiritual in some ways,” she said. “I’m in nature a lot more. I’m taking time to be in the moment a lot more. I’m trying to put this in perspective, thinking about life, and the frailty of life, and how things can change in a heartbeat.”

Rabbi Tilsen said that he’ll never know how different Jewish people are responding to the turmoil of the pandemic. Some people turn toward religion and God in times of crisis, others turn away. “Jewish theology is not doctrinal; so much theology is implicit. We don’t have a formal vision or idea of what God is,” said Tilsen. “Judaism has to do with the search for truth and it means rejecting ideas that are clearly falsifiable or clearly wrong. God often just comes from a sense of awe at the world.”

On the Fourth of July at noon, as Noam returned the Torah scroll to the ark, those present rose from their chairs and praised God a final time before the service closed. “The voice of Adonai stirs the wilderness. The voice of Adonai strips the forest bare…” they sang in Hebrew as one voice. Above them, thick foliage rustled and the sun stung their skin.

In ones and twos, the faithful took their leave, stacking the chairs and tomes of scripture and prayer books onto the cart as they went. Nash’s low heels clicked on the baked tarmac as she walked away. The synagogue staff wheeled the trolley, heavy and laden with the Law, back into the cool sanctuary, where it would wait seven days until the next Sabbath.

—Ko Lyn Cheang is a senior in Grace Hopper College and TNJ’s recipient of the Ed Bennett Memorial Fund.