Just six blocks south of the New Haven Green, the strongest signs of life are the distant roar of traffic on the Route 34 Connector and the less-regular stream of cars here on Church Street South. A schoolbus drops off a girl carrying a backpack with a cartoon design whose mother waits to walk her home. I watch two boys behind them bike back and forth on the sidewalk. They are the only pedestrians on this boulevard. Though I’ve been told that the long beige buildings to my left hold three hundred residences, the nearly-empty streets of the neighborhood make that hard to believe.

“CHURCH STREET REDEFINED: A VITAL MAIN STREET FOR NEW HAVEN’S HILL-TO-DOWNTOWN DISTRICT.” The black letters crown the city development plans that were unveiled at a public meeting at Hill Central School on September 24. The plans are part of an effort by city officials to dramatically re-envision the future of this area between Union Station, Yale School of Medicine, and downtown. Within a decade, the street I am walking along could be thronged with residents of different ages, incomes, and backgrounds living in new four-to-six-story homes. They could take long walks through a neighborhood bordered by an array of shops and restaurants.

If they succeed at redefining Church Street, the project will be the second major identity shift for the area in the past sixty years. What officials now sterilely label as the “Hill-to-Downtown District” once formed part of the vibrant Oak Street neighborhood. In 1959, a diverse but poor community of immigrants lived in the area. It was culturally rich, but physically poor, and officials fixated on the limited infrastructure. Instead of improving living conditions, the government decided to demolish the neighborhood altogether. Three thousand people were displaced. Subsidized highways and mass production were making the automobile a ubiquitous presence in American culture, and the project aimed to clear the way for a freeway—the Route 34 Connector—to send traffic from Interstate 95 smoothly into downtown New Haven. City planners envisioned a city in which commerce would flow, unimpeded by the Oak Street neighborhood. Mayor Richard C. Lee was certain that New Haven would become “a slumless city—the first in the nation.”

But rather than supporting an urban core, the highway accelerated a mass exodus to the suburbs. It served commuters, not the dwindling surrounding population. By the time political momentum for Lee’s mid-century urban renewal project ran out, plans for a longer highway were scrapped—the connector now splits at the hulking Air Rights Garage into the two forks of Legion Avenue—and the promises of a renewed city were unfulfilled. With the Oak Street neighborhood permanently razed, the connector became infamous for dividing the city in two—separating the Hill neighborhood to the south from downtown New Haven. Today, the several-block trek from the Hill to the Green, or from Yale School of Medicine to the heart of campus, is a knot of over- and underpasses. Blocks are long, and loud with the roar of speeding cars.

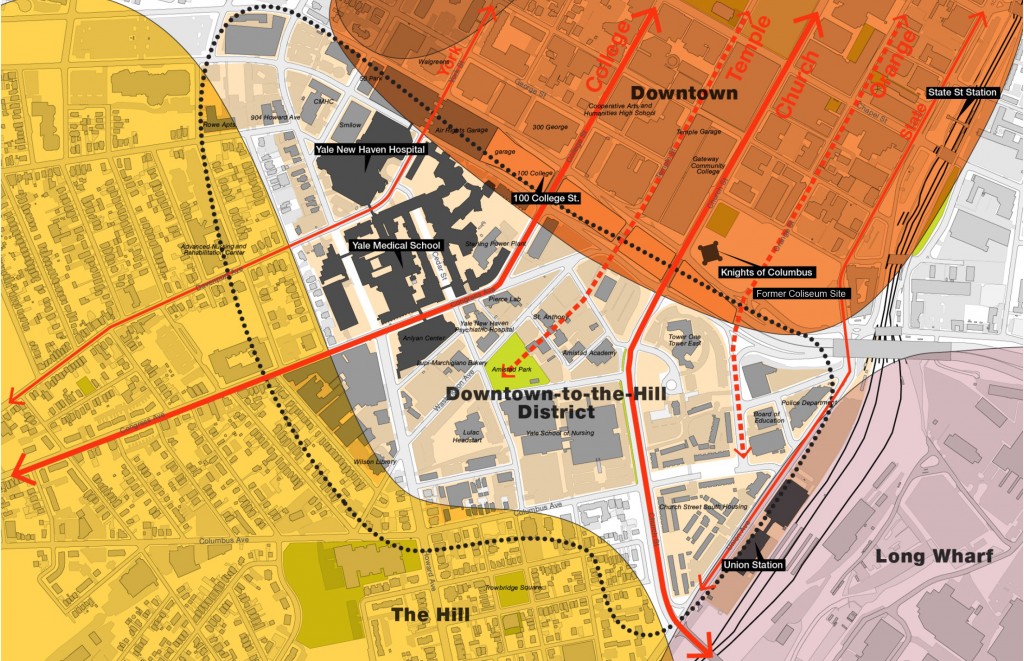

New initiatives are aimed at reenergizing the urban wasteland created by the connector. In 2007, the city was awarded a federal Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grant to convert the eastern section of Route 34, which runs from Park Street to Union Avenue, into two “urban boulevards”—with traffic lights, narrower lanes, and a lower speed limit—alongside new developments. The ambitious project, called Downtown Crossing, will eventually lower the College Street overpass to street level. Phase I of construction will replace a segment of highway at 100 College Street with a new pharmaceutical skyscraper. Ground was first broken in June.

The Downtown Crossing project will pave the way for a larger—and, ideally, a more coherent—urban plan. To achieve this, as the Downtown Crossing project advances, the city is simultaneously redesigning the area lying south of the Connector, between Union Station and the medical school. Called “Hill-to-Downtown,” the expansive new project includes two large residential-and-retail developments, the first across the street from Union Station and the second on a more upscale site in the former Coliseum property just north of Route 34. The first development sits on Church Street, which in the new plan forms the centerpiece of the district, with more stores, housing, and greenspace. The district will host new office and lab buildings, most of them serving the biomedical industry that currently dominates the area around the medical school on the district’s western side. Residents and officials hope that the changes brought by this pair of major projects will reap social and economic benefits for the neighborhood, transforming an area still feeling the effects of the sixties-era urban renewal into a community.

**

“You could classify Oak Street back then as a slum,” acknowledged Robert Silverman in a 2004 interview, “but it was a thriving slum. People were living in the houses, business was in the stores, and business was being done.

Silverman lived in the Oak Street neighborhood until it was razed. Along with several other former residents, he lent his voice to a historical project undertaken through the Manuscripts and Archives department of Yale’s Sterling Memorial Library in the early 2000s. The New Haven Oral History Project compiled voice interviews of these New Havenites into an exhibit called “Life in the Model City,” a reference to the Johnson administration’s national Model Cities project, which had been inspired by Lee’s program for New Haven. Silverman remembers urban renewal with bitterness; it displaced Jewish organizations he had belonged to, and erased many other features of a previously flourishing community.

Today, few homes remain in the area where Oak Street disappeared, and residents nearby miss these hallmarks of a lively neighborhood. “There’s a lot of nostalgia for what used to be,” says Chris Soto, who works for the mayor’s office’s Livable City Initiative.

There is good reason to look back with longing. Since the removal of the so-called slum, the Hill-to-Downtown area has felt lifeless and bleak. On Church Street, vast swaths of surface-level parking surround squat office and medical buildings. Iron fences and security cameras remind passersby that they are not welcome.

**

Crossing the street on a sunny Tuesday, I start to reconsider. Despite the city’s mistakes, some features of a community have clearly taken root. The beige buildings of the government-subsidized Church Street South housing complex seem lived-in. Residents stroll around and lounge beneath the trees of a small designated greenspace. Groups of people gather on the balconies or sidewalks, chatting in Spanish and English. A young man stands at the corner with a skateboard and a spaniel. This atmosphere gives me hope that I had misinterpreted the foreboding atmosphere. Perhaps Church Street South has retained the communal atmosphere that I thought had been lost decades ago. A family jokes and laughs together in front of their apartment door. I approach the group and ask them what it is like to live there. Two of them introduce themselves as Shanequa and Tangie, and, asking not to be identified by their last names, tell me:

“Shitty,” Shanequa says, then adds, pausing between each word, “Trashy. Messed-up. Terrible.”

At each word, the others nod. “Everything’s falling apart,” Shanequa says. Problems abound, and the street feels unsafe for the families who live there. “The area point-blank is bad, with drug dealers, and our kids having to see it all.”

To make Church Street South a better home, developers would “have to do a lot of rearrangement of the people. They’d need to rebuild it, step up security, make it safer for kids,” she adds.

Developers have made an attempt to respond to residents’ concerns. Representatives from the mayor’s office, as well as from Goody Clancy, the architecture firm hired by the city to lead the project, held a series of public meetings at Hill Central School. After listening to feedback from New Havenites, particularly residents of Hill neighborhood and Church Street South, the firm spent three months narrowing the ideas into a single drafted plan, unveiled on September 24.

At the meeting, I listened as David Spillane, Goody Clancy’s director of planning and urban design, explained the plan behind that promising title: CHURCH STREET REDEFINED. He envisions a thriving district centered around Church Street as its main commercial and residential street.

At previous meetings, Church Street South residents had advocated for grocery stores, pharmacies, and other shops that would serve their daily needs. Planners for Goody Clancy and the city have acknowledged these requests, but because the properties are privately owned, they are vague about which businesses will eventually move in there. “They potentially serve residents, they potentially serve commuters,” Spillane says. “Over time the goal would be to get a real mix here.” The city is in discussions with the private owners of Church Street South.

Renowned urban designer Julie Campoli emphasizes that urban vibrancy begins with density—in order to make a city street lively, a large number of people must live in a relatively small area. But a large population alone will not create community. In New Haven, the Church Street South planners have their own ideas about what will make this happen: they hope to build mixed-income, mixed-age housing where residents feel safe. Current residences there would be torn down to make way for these developments.

Campoli wants to upend the idea that affordable housing has to be unpleasant. At an October 1 talk at the New Haven Hall of Records, she challenged participants’ preconceptions. She showed the audience vibrant housing developments at various communities throughout the country and gave them handheld clickers to vote on whether the houses were market-rate or affordable. The homes blended in attractively with their cityscapes, and many had small gardens for residents to tend. The audience members frequently guessed incorrectly.

Talking to me outside the residential complex on Church Street, Tangie said that she thought the current buildings look “like jail”; instead, she would like to live somewhere that people admire, where “when you walk you go, ‘Damn.’” Shanequa adds, “I don’t feel that just because we can’t afford it, we should have to live like that.”

The new plan makes room for between six hundred and 750 units, but just twenty percent are affordable. This would halve the current number of federally-subsidized units to 150. Though they are anxious for change, this and any additional plans to replace these units elsewhere leave some residents wondering where they will fit into the project. “They need to hurry up and do it!” says Shanequa. “Hurry up and kick you out,” quips one of her friends.

**

Walking through the Hill-to-Downtown district is challenging. From Church Street South, I turn onto Lafayette Street and quickly find myself thwarted. This street was a prominent place for business and housing in the old Oak Street neighborhood. Now the road, which abuts St. Basil the Great Greek Orthodox Church and the Tower Hill/Tower East assisted living facilities, ends in a fenced parking lot and a walking path between the buildings of Church Street South. Two men on their balcony stare. The paths do not feel like public space, and I backtrack.

For the casual walker, there is no clear or intuitive route to Union Station. I start again down Church Street South, continuing along its length until I am able to turn at a sharp angle. From here, it is a nerve-wracking jay-walk across a large intersection before I am headed north on Union Street toward the station.

A few days later, I am poring over the recently unveiled Hill-to-Downtown plan alongside Anstress Farwell, president of the New Haven Urban Design League. I notice that, as part of the development, Lafayette Street will be rerouted and extended. But will it be walkable?

“There are some good things about the plan,” Farwell says, mainly “the basic objectives to make very direct and intuitive connections to downtown.” Direct routes tend to improve “walkability,” a buzzword among urban designers; it is often used in tandem with the phrase Transit Oriented Development (TOD), which prioritizes placing a mix of housing and retail within easy walking distance of transit.

The new urban boulevard is designed to correct the problems caused by building a highway in the middle of a city. Kelly Murphy, New Haven’s director of economic development, remarks, “A highway doesn’t really generate jobs or income or create vitality, but we think that what we’re doing to remove the highway will.” An urban street, rather than serving as a thruway for suburban commuters, should serve as a place to walk, congregate, browse, shop—in short, a place that can be lived in.

**

Unlike the suburban population that was to be served by Connector in the fifties and sixties, a growing number of people today either prefer not to drive or cannot afford cars. According to the 2008 American Community Survey census, close to half of commuters in New Haven reached work without solitary driving—fourteen percent used public transit, thirteen percent walked, eleven percent carpooled, and two percent biked. Fewer young people in the U.S. own cars, and they are increasingly living in cities. 2011 marked the first time in a century that cities grew at a faster rate than their surrounding suburbs. With increased migration to city centers rather than suburbs, the same forces that rendered Route 34 obsolete should prompt the design of cities less reliant on cars.

These shifts emphasize the importance of making New Haven a place where people can explore the city by foot—and the ways in which the current proposal falls short. Back in the Urban Design League office, I find myself nodding as Anstress Farwell describes some necessary improvements.

“For instance,” she says, pointing to a proposed park near Church Street South, drawn in a line with Union Station, “you wouldn’t know to go around the park to downtown.” When pedestrians are frustrated, they often choose not to walk at all. This problem extends to the rest of the plans for the neighborhood. “There still isn’t an intuitive way to know that you can go downtown or to the med school.”

The city is set up in such a way that people are expected to drive to the station, but residents are questioning this layout. In the community meeting, a young man raises his hand: “Is there any talk about changing mass transit included in this plan?”

Erik Johnson dodges the question: “That’s a separate conversation.”

Urban designers and residents disagree. People taking the train would not need to park near Union Station if buses ran from their homes to the station. At the moment, Goody Clancy has drawn up an additional garage to supplement the massive one already abutting Union Station. Bus routes will not be added, however, if parking additions are a central component of the plan. By trying to solve the problem of how cars fit into place, they ignore the way that people would like to travel from one place to another.

I repeat the question of transit to Kelly Murphy, administrator of the mayor’s office’s economic development department. She evades: “Generally, the service comes after the need.”

Residents already feel that need. Some urban planning advocates who have long been at work designing a transit- and person-centric New Haven object to the indefinitely long delay in taking action. “There’s really a strong community of people that understand this and have been very active for years talking about this,” Farwell argues. “The city has adopted the language but not the principles.”

**

As I walk west and turn up College Street, I watch as bicyclists weave around construction at a nearby bridge over Route 34 and lean on the curbs while waiting for the slow Frontage Road traffic light to change. Depending on decisions made in the planning process, the bicyclists’ route after development could become much more pleasant—or remain tedious. In place of a highway, the two new “urban boulevards” are meant to create easier routes for New Haven’s already-thriving bicycling community. After Route 34 is dissolved and the section of College Street rebuilt, bike lanes will be added.

Elm City Cycling, a bicycling advocacy group, was an early and vocal supporter of the Downtown Crossing project even as others raised concerns. But it publicly withdrew its support in August 2012. The city had dismissed some proposals for two-lane or four-lane city streets in favor of eight lanes of traffic. The group’s public statement explains that they grew disenchanted with the project. What had begun as a “bold vision” had become a “road-widening project that repeats the mistakes of the past.”

“There was really a failure to bring it up to today’s desired standards,” Elm City Cycling’s spokesperson, Mark Abraham, tells me. “I think the standards have to do with equitable access to all ages, all abilities, and making it more walkable, more bikable. You’re not going to see children riding on these roads alone.”

**

Looking back from the roadwork toward the Hill-to-Downtown area, where construction has yet to begin, I still have questions. Despite the many meetings and published material, the plans for the district remain more tenuous than their bold headings suggest. When Mayor John DeStefano, Jr., leaves office at the end of the year, many appointed city officials may also be on their way out. The execution of any plan will inevitably rely on the choices of the new administration, and the vision set out for Hill-to-Downtown could change drastically.

City planners are hurrying to set the current plan in stone before the mayor’s term ends. At the September 24 meeting, Erik Johnson invited interested residents to be part of a steering committee that will champion the presented Church Street plan. “When Kelly [Murphy] and I aren’t here and other people aren’t around, we want to make sure that there is a community voice.” The plan will go before the city planning commission on November 20. “We want you to come with us to talk about our plan,” Johnson says to the assembled community members. “After we go to the planning commission, we are going to take this to the Board of Aldermen in December…We would like you to be there.”

Many aspects of the Hill to Downtown plan could change over the fifteen to twenty years it will take for the Downtown Crossing project to be completed. But just by agreeing to remove Route 34, the city has shown that it believes that New Haven can be a better and more livable city. I recall Shanequa’s words: “They need to hurry up and do it.”

**

Past the treacherous highway overpass, I thread east through the park behind the Knights of Columbus tower, to the site where the New Haven Coliseum sports arena stood from 1972 until the city imploded it in 2007. The Knights of Columbus tower casts a shadow over the sweeping parking lot. In the future, this lot could be entirely transformed as part of the Hill-to-Downtown projects: a developer hired by the city submitted a design featuring a town square with apartments, restaurants, and top-of-the-line wine shops; later plans include a luxury hotel and a corporate office tower. The estimated cost of the project is $250-$350 million.

After the meeting, Chris Soto says of the plan, “In their scheme, you see a hotel. You’re also seeing a lot more activated streetscape. The folks on the street aren’t just walking by businesses, it’s more stopping and looking and whatnot.”

Many details of the Coliseum development would be out of place in a development at Church Street South, where residents are hoping for grocery stores. But it evokes a style of city life that the designers think Hill-to-Downtown district could aspire to: a place where people can live, work, and play. A revitalized Church Street, if executed well, could be just as lively as the architectural designs. People could be excited to gather and to walk down in the new Main Street. Instead of living among the ghosts of a once-vibrant neighborhood, residents could find a place to call home.