The walls of Nick Provost’s suburban Connecticut living room are decorated with a taxidermied deer head and a few grandmotherish tchotchkes in the colors of the American flag. A flat-screen television occupies one corner. Provost’s three blonde daughters, ages 9, 8, and 7, chase each other through the room. About a dozen people sit around on couches, chairs, and stools.

Nick Provost, a boyish 28-year-old with a warm, crooked smile, lies on the floor. A black strap called a Hasty Harness is wrapped between his legs, behind his back and around his armpits. The people sitting in a semicircle around his prone body watch carefully as Jason Wyman, a barrel-chested former army medic whose beard looks long enough to reach his navel, holds the ends of the strap and pulls up. One of Wyman’s arms is covered in ornate gothic script that reads, “From the gates of hell.” On the other arm is printed “To the halls of Valhalla.” Wyman easily drags Provost’s muscular six-foot frame using the lightweight contraption. Provost groans as the straps tightens around his upper thighs.

“My primary rule: pain is the patient’s problem,” Wyman says.

The observers had come to learn, from a combat medic, how to care for the victims of countless violent scenarios: mall shootings, car accidents, pipe bomb explosions, home invasions, urban riots. The type of disaster that might require a Hasty Harness seemed far away from Provost’s living room on that grey Saturday in November. But for the people watching Provost squirm—members of a Facebook group he runs called the Community Rapid Response Team (CRRT)—planning for the worst is a way of life. Their group is a small part of the vast network of Americans interested in disaster preparedness and self-defense. The “prepper” lifestyle was made famous by the National Geographic show Doomsday Preppers—a lovechild of TLC’s Hoarders and MTV’s Cribs, with the addition of existential and often politicized dread. But many CRRT members, including Provost, reject that label, conscious of the stereotype that preppers are paranoid, irrational, or crazy.

“We’re not a militia, we’re not survivalist, we’re not preppers,” Provost says. “We go about our normal lives and we prepare to take action in bad situations.”

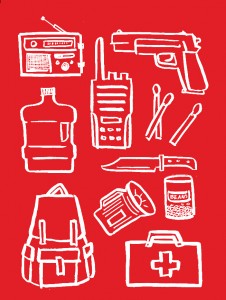

Those “bad situations” run the gamut from a massive snowstorm to a home invasion. The good news is that modernity offers up a host of useful gadgets and gizmos, approved by the U.S. military and available for purchase online or at particularly well-supplied outdoor equipment stores. With a little ingenuity and a bit of cash (the Hasty Harness costs just twenty-five dollars), the average American can feel ready to fight whatever Mother Nature or a fellow human being dishes out.

A former soldier now supervising shifts at a plant that manufactures nuts and bolts, Provost established CRRT in the summer of 2014. CRRT became the latest addition to a virtual world of disaster preparedness and self-sufficiency communities, joining the Connecticut Preppers group (“Preparation for when ‘IT’ happens!”) and the Connecticut Preppers Network page’s 900+ members. The CRRT group now has over 170 members, twelve of whom paid Wyman fifty dollars to attend the medical course. Twenty to thirty regularly attend events.

Jason Wyman, the medical instructor, spent four years as a military medic in Iraq. He was there in 2005, during the insurgency. When he came home to Maine, he brought with him stories of shrapnel-studded organs, jellied brains, exploded limbs, the comrades he had saved and those he hadn’t. Now, as an instructor at the self-defense training company Muzzle Front, he teaches civilians how to do what he did. But instead of gearing up for patrol in Fallujah, they’re protecting themselves for a trip to the mall.

The members of the CRRT focus on everyday disasters. I spoke with people who use downtime at work to browse the web for supplies and devote weekends to practicing marksmanship. For others, a trip to the grocery store is an occasion to pick up a few extra cans of beans to add to their stockpile. One man begins his daily commute by checking that the bag filled with medical supplies and enough food and water for 72 hours is still tucked safely in his car’s back seat. They rarely discuss such behavior with outsiders, who often dismiss these actions as paranoid. Quietly, methodically, they stock the basement shelves.

Driven in part by nostalgia, members of the CRRT ultimately advocate self-sufficiency. They invoke the lifestyles of their grandparents to explain why they do what they do. Two generations ago, they insist, every household in America stocked enough food to last a week without power or transportation. Kids learned basic survival skills on camping trips, everyone knew their neighbors, and journalists told the truth. The off-screen, Regular Joe disaster preparedness movement is rooted in the belief that Americans back then had less to fear, when the national lifestyle was one of communal sufficiency. Their behavior is a response to distinctly contemporary events. They’re often violent, and occasionally horrific: September 11, mass shootings, the financial meltdown. Responding to these events requires preppers, despite their nostalgia for a bygone way of life, to embrace the complex technology and grim outlook that pervade our times. I am not surprised, then, that Jason Wyman was teaching us how to conduct triage, not how to plant victory gardens.

***

The group in Provost’s living room reflects the demographics of the broader disaster preparedness crowd, estimated at three million Americans and growing: mostly male, mostly white, mostly middle-aged.

Wyman’s instruction takes up the better part of two hours, during which the audience asks many questions. Should you try to remove shrapnel from a patient? Where can you buy the equipment to set up an IV unit? Can a tampon be used to stop bleeding from bullet wounds?

When he finishes covering the material, Wyman pulls out a large brown pack and takes out its contents to show everyone what to consider purchasing for their own medical equipment kit.

“This is my fuckin’ murse,” he says. “Got multiple kinds of beard lotion because that shit’s important.” There are also eye drops, bandages, Ace wrap, gloves, a bandage with a plastic closure apparatus, and a large holster called a “thigh rig” that allows the wearer to strap supplies around their hips and both legs.

After showing off his equipment, Wyman tells us to present our medical emergency kits so he can evaluate their strengths and weaknesses. On the couch beside me, a middle-aged man in a neat button-down shirt sets down the yellow legal pad and pen with which he’s been carefully taking notes.

“My kit’s in the car, but I’m not even going to go get it,” he says, seeming ashamed of and a little guilty about his substandard equipment.

He introduced himself as Frank. Frank now lives in the greater Hartford area and works in real estate, but he traces his prepper impulse back to the long gasoline lines he witnessed as a 6-year-old in Connecticut during the 1973 oil embargo. He learned then that basic assumptions of American life could be quickly and unpredictably undermined, though he didn’t start prepping in earnest until a few years ago. He can’t pinpoint a specific event or experience that led him to begin stockpiling food, taking self-defense classes, and researching humanity’s long history of disasters, but he thinks the recession of 2008 made the world seem a more fragile place.

In the scores of credit card-carrying customers at the grocery store, Frank sees a contemporary insecurity. What will happen if the power goes out? Or if the computer systems that allow cashless transactions fail? The everyday technology that makes the modern American lifestyle so convenient, so easy, so comfortable, Frank says, is particularly vulnerable to attack or malfunction.

Frank can rattle off a cascading list of crises ending at the present: in 1859, a major coronal mass ejection—a burst of solar wind that caused electrical disturbances on earth; in the nineteen-seventies, the gasoline shortages; September 11; Hurricane Katrina; the Great Recession; Hurricane Sandy; the blizzard Nemo. His primary concerns are natural disasters, financial crises, and home invasion. He considers the more extreme potentialities only as a kind of enjoyable thought experiment on prepper forums and Facebook groups.

“We’ll discuss what we would do, like if you knew an asteroid was coming,” he explains. “Fun stuff.”

Frank is a generalist. Like others I meet, he prides himself on not wasting mental energy and resources seriously preparing for unlikely events such as the asteroid collision. His approach to general preparedness is systematic and disciplined. And though many of the disasters he fears are caused by modern technology, that same technology has enabled him to connect with thousands of like-minded individuals to share thoughts on preparedness.

Robert Higgins, one of the CRRT’s most active members, owns Muzzle Front, the self-defense training business where Wyman works. Higgins thinks that the actions of American preppers now congregating en masse online would have seemed unremarkable a generation ago. He believes that contemporary Americans embrace convenience more than ever before. As American urbanization has continued, camping and outdoor activities interest people less than they once did. In earlier generations, when people lived farther from shopping centers and had stronger memories of hardship, they were sturdier. Higgins’s parents were born just after the Great Depression, and they grew vegetables and canned them for the winter in his childhood. Sometime in the nineteen-nineties, he realized that such behavior was increasingly unusual.

“The more people had easy access to things, the less they stored things in their home,” he says. “Fiscally that can make sense. Why have anything sitting on your shelf when you could go get it at any time and still have access to the capital should [a disaster] arrive?”

While Frank considers his online prepping research and socializing fun, others consider it deadly serious business. Higgins teaches a host of self-defense classes at Muzzle Front. The company’s courses offer “tactical” self-defense training, which means that instead of firing their pistols at a paper target or performing roundhouse kicks on a dummy, participants learn to deal with surprise attacks. “Attempting a particular punt or kick may reveal that a preexisting injury prevents the effective use of that particular movement,” Muzzle Front’s website explains. “Better to discover it in the dojo, than in some back alley with Pookie the Crackhead.”

Some of the people interested in his courses harbor fears that Higgins considers extreme. He doesn’t cater to such people, whom he describes as “on the brink of paranoia,” but rather to those who have what he considers legitimate concerns and reasonable plans to address them. Sitting in Blue State Coffee on Wall Street, he tells of his encounters with people on the fringe. Higgins once went to a meeting of the Connecticut State Militia, a group that prepares to fight back in the event of a government attack on the American people. Their Facebook group is closed but offers a description that includes the emphatic claim that “THIS IS AMERICA, NOT RUSSIA, NOT CUBA, NOT CHINA AND SURE AS HELL ISNT NAZI GERMANY!!!!”

When he arrived, Higgins found a group of people who represented the sect of preppers from which he distances himself.

“I said to them, ‘You look like a bunch of white supremacists, you look like you’re ready to attack the world, and you look like a bunch of middle-to-old-aged white guys,’” Higgins says. “I offered to help steer them in the right direction, and leadership decided that they didn’t need that help. They were an interesting group of individuals.”

As Higgins explains the underground landscape of Connecticut’s radicals, a man near us in Blue State seems to be tilting his head in to listen.

“It’s not polite to eavesdrop,” Higgins rebukes him.

I don’t blame the man for listening. I, too, find it hard to understand how someone could see America on the road to becoming a new Third Reich.

Higgins views this extremism as a predictable outcome of the way we consume news and information today. Dark rumors spread rapidly across computer screens and televisions. When Frank says he believes today’s America faces a uniquely volatile economic and international relations landscape, referencing the crisis in Crimea, quantitative easing, ISIS, and cyber attacks, it’s hard to tell if we actually face more threats, or if we are simply more aware of them. Perhaps the past is appealing because back then we were less cognizant of danger.

The members of CRRT draw a sharp line between themselves and extremists. The CRRT doesn’t obsess over government plots like the Connecticut Militia. Frank, who owns a pistol for self-defense and a rifle for hunting, seems to enjoy preparing for disasters in the same way other people enjoy crafting or training for triathlons. But when I ask how he spells his last name, he hesitates. He worried about giving away too many identifying details.

“We talk about this thing called op-sec, operational security,” he explains. “If something was to hit the fan, they would know where to get my supplies.”

***

Though the Internet plays a crucial role in connecting preparedness-minded Americans, the mission of the CRRT is to build community in person. In addition to the medical training class, the group has participated in hikes, a cold-weather pistol technique class, and overnight camping trips. Provost’s cousin, Adam Hummel, believes that what makes CRRT special is its rejection of the isolation instinct that leads preppers to hoard knowledge and resources. He recently posted a message encouraging members to ask each other for help with spring cleaning projects and renovations.

Provost sometimes gets into virtual arguments, defending cooperation within families and communities as key to survival. In response to preppers who insist that, come the Big One, they will barricade themselves inside their homes with their weapons and stockpiled food, Provost always poses the same question:

“What happens when I come burn your house down?” he asks. “You have to come out of the house.”

Provost’s disdain for aggressive individualism is a far cry from the blunt self-interest prevalent on other prepper forums. Alex Kingsbury, a self-described moderate prepper I met on the Connecticut forum of the American Prepper Network site, said he doubted many people would want to be interviewed because they fear compromising their identity, location and supplies.

“I don’t know you, but I think it’s probably pretty unlikely that you’ll show up at my house with a gun to steal my beans,” Kingsbury says.

Given their emphasis on amassing supplies and equipment, catering to preppers is big business across the country. Companies offer everything from fairly standard camping supplies to vast quantities of dehydrated food to ready-to-use nuclear bunkers.

“There’s a whole industry out there,” Hummel says.

Hummel, who serves as the group’s IT specialist, established a program on Amazon that allows equipment vendors to sell their products to his members at discounted prices. Sitting at his office desk, he pulls up the group’s Amazon page and lists off items members have bought: water bottle holders, fishing kits, emergency blankets, and a physician’s desk reference.

Within this community, as in many American communities, the act of consumption bonds people together. The CRRT members in Provost’s living room ooh and aah at the disaster gear Wyman shows off the way I imagine Greenwich matriarchs admire expensive clothing at trunk shows.

Some companies marketed to preppers focus on a particular genre of disaster. Based in Gonzales, Texas, a company called Ki4u.com sells items to help people survive nuclear disaster. An $815 “Radiation Safety Combo Package” includes radiation detection devices, KI tablets and facemasks to minimize contamination, as well as several books and pamphlets produced by the company. One is entitled “The Good News About Nuclear Destruction!”

Other companies profit by selling “situational awareness,” according to Stephen Austakalnis, who founded AlertsUSA in the aftermath of September 11 to help people access immediate information about threats emanating from all over the globe. His team of six spends all day monitoring news outlets around the world. When they notice a potentially troubling development—say, the murder of a Mexican politician by a drug cartel or an announcement that American troops will be sent to battle Ebola in West Africa—they send an alert to twenty thousand subscribers. The subscription is ninety-nine dollars per year.

The American Preppers Network offers users the opportunity to become “Gold Members.” For sixty dollars annually, the Gold Member gains access to an exclusive newsletter, special discounts at shops that offer survival food and supplies, and a private Facebook page to connect with others similarly dedicated to surviving disaster. For five hundred dollars, one can obtain “Platinum Lifetime Membership” and receive these benefits for life.

In Connecticut, the Old Saybrook storefront of Harris Outdoors began as an Amazon vendor account. Bob Harris, the owner, bought and resold outdoor supplies he considered high quality, and soon local customers were filling his driveway, eager to pick up equipment instead of paying for shipping. Now, he does almost all his sales out of the shop he opened three years ago and recently doubled in size. He sees about twenty to thirty customers a week, estimating that at least half are preppers.

“Our more reliable customers seem to be a fairly tight-knit community,” Harris tells me over the phone. “As far as our success story, the biggest thing has been word of mouth.”

Harris considers himself a “common-sense prepper.” He stocks his home with extra food and practices his outdoor survival skills through backpacking trips. When I visit his shop in March, the inside looks similar to an REI. There are sleeping bags, water filtration devices, shoes, backpacks, and first aid kits. A couple spends at least half an hour chatting with Harris about his collection of duck decoys, set up in the back corner of the store.

Harris admits there is a good deal of overlap between backpackers and preppers, and it can be hard to tell them apart based on their purchases. Many outdoor enthusiasts read the shop’s slogan, “Prepared for every adventure,” and don’t recognize the range of meanings the words “prepared” and “adventure” can assume. Talking to Frank, Higgins, and others, I get the impression that they might relish a shit-hits-the-fan moment as a kind of adventure, maybe even as an opportunity for heroism. But they still bear little resemblance to the Doomsday Preppers who are morbidly convinced of imminent destruction. I ask Harris what he thinks about the show and its depiction of excessive consumption of niche products as the route to salvation. He says the people on Doomsday Preppers just aren’t very good at prepping.

“Honestly, I think they’re stupid to be on that show, because they’re disclosing all the things you shouldn’t be disclosing,” he says, referencing their exhibition of their bunkers, food supplies, and backup generators, now vulnerable to attack or theft. “They sold themselves to the devil.”

Harris’s response to Doomsday Preppers points to the eventual limits of some preppers’ desire to help one another in crisis situations. A certain degree of secrecy is crucial to survive in a world of scarcity and competition. Even when the catastrophic event is a natural disaster, the use of physical force against other people must be on the table. As Frank puts it, New Orleans descended into anarchy within a few days of Hurricane Katrina. Stockpiled food is only as good as your ability to defend it. No one at the medical training class mentioned it, but the hotdogs and potato chips in Provost’s kitchen were secure; after one woman had to remove her pistol holster to try on Wyman’s thigh rig, I looked around the room and realized nearly every adult was carrying a weapon.

***

At Wyman’s course, someone’s box of bullets spills over a coffee table in the Provosts’ living room. One of Provost’s daughters wanders through. She leans over the coffee table and rolls the bullets under her tiny fingers. Their cold metal casing slides across the wooden surface. The potential for violence is omnipresent, even casual, but there’s not much discussion about how to take down the gunman or the home invader. The class is all about what to do once the fighting stops.

Because self-defense seems to be a crucial component of prepping, I wanted to talk with people as they actively work on their ability to fight. In February, I learned from the CRRT Facebook group about a course taking place one weekend at King 33, a “public safety training” center in Southington. The class was a two-day home-defense course taught by a special forces veteran named Larry Vickers. Participants would learn how to use firearms to defend their homes and businesses from attack. Topics to be covered included “weapons manipulation, movement and approaches, room entry and domination, family member rescues, safe room set-up and defense, low light encounters, surgical shooting exercises, etc.” The course cost six hundred dollars. There would be actual shooting.

The King 33 facility is located off Highway 84 in a complex of former warehouses. King 33’s door is tiny, unremarkable relative to the enormous warehouse behind it. At least fifty cars sprawl across the parking lot, bearing license plates from Pennsylvania, New York, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Delaware.

I step inside a small foyer with a television, a few chairs, and a desk with a nearly emptied box of Dunkin’ Donuts doughnut holes. A man and woman who look to be in their 70s stand up from the desk. They are Pat and John Michaels, friends of King 33’s owner Chris Fields, a special operations veteran. The couple greets me with expressions first of concern, because the door is opening twenty minutes late, and then confusion. I don’t look like their typical client. After I explain that I’d like to meet participants in the course, John leaves through a door across the room to search for someone to ask about my request, leaving Pat and me to chat. A television is set to Fox News. On screen, a boat is being pummeled by violent waves somewhere in the Atlantic, waiting for rescue.

Pat tells me about the courses King 33 offers: pistol safety, marksmanship, self-defense, women-only self-defense, and a slew of courses designed for law enforcement personnel. The self-defense classes don’t require participants to use firearms, she says. “You should take it. Especially living in New Haven.”

After a few minutes, John Michaels returns and leads me through the other door into a much larger space—so large a car is parked inside. John explains that students use the car to practice defending themselves from an attacker waiting for shoppers incapacitated by their bounteous purchases.

A higher-up comes in and apologizes: the course isn’t run by King 33 but by Larry Vickers, so they can’t give me permission to go inside the training facility or meet participants.

“They’re good people, but they’re private people,” Michaels says.

Besides, it’s a live-fire course with bullets that can draw blood, and I don’t have proper protective gear. It’s important that participants feel a real sense of danger and potential pain, because otherwise the experience won’t mimic real life, when the man trying to hold you hostage in your own home won’t be shooting rubber bullets.

I say goodbye to John and Pat and walk back out into the snow, past the dozens of cars, empty storage units and a rusting water tower. I start walking down the road, trudging away from King 33. I’ve only gone a few hundred feet before a car pulls up beside me and the driver rolls down her window. She smiles at me and asks if I need a ride. I tell her no, thank you.

“Are you sure?” she nods her head at the toddler in the back seat. “We’re just headed up the road to Stop and Shop. It’s no trouble.”

That’s all right, I say.

“Oh, are you staying at the park?” she gestures behind her. I turn and look down the long, empty road, which must stretch onward to a place where young people camp even in the winter. It strikes me that she is probably not aware that close by, dozens of people are running around a warehouse in bulletproof vests, shooting at each other, diligently preparing to protect their families. She does not realize the risk she takes in driving through the snow without an emergency supply of food and medicine. She’s not thinking about how vulnerable she makes herself simply by living in America today—talking to strangers, paying for her groceries with a credit card, trusting that it will all be O.K.

I think about Frank, who seems as typical as the woman now offering me a ride. He told me, at the end of the medical disaster class, “You just never know what’s going to happen.”

He’s right, of course. The woman and her child drive away to the Stop and Shop, where the fluorescent lights are always bright, the number of cereal brands dazzles, and the imported vegetables shine. I keep walking through the snow.