The day her son Brent died, Karine Heard had a migraine. She was at a drive-through bank teller when he called, asking whether she had a piece of his mail at home. “Probably. I’ll have to look,” she whispered into her phone, trying to be discreet. She thought about asking him to lunch but decided against it because of her headache. Brent told her he needed a document that matched the name on his ID so he could check into a methadone clinic—another attempt at getting clean.

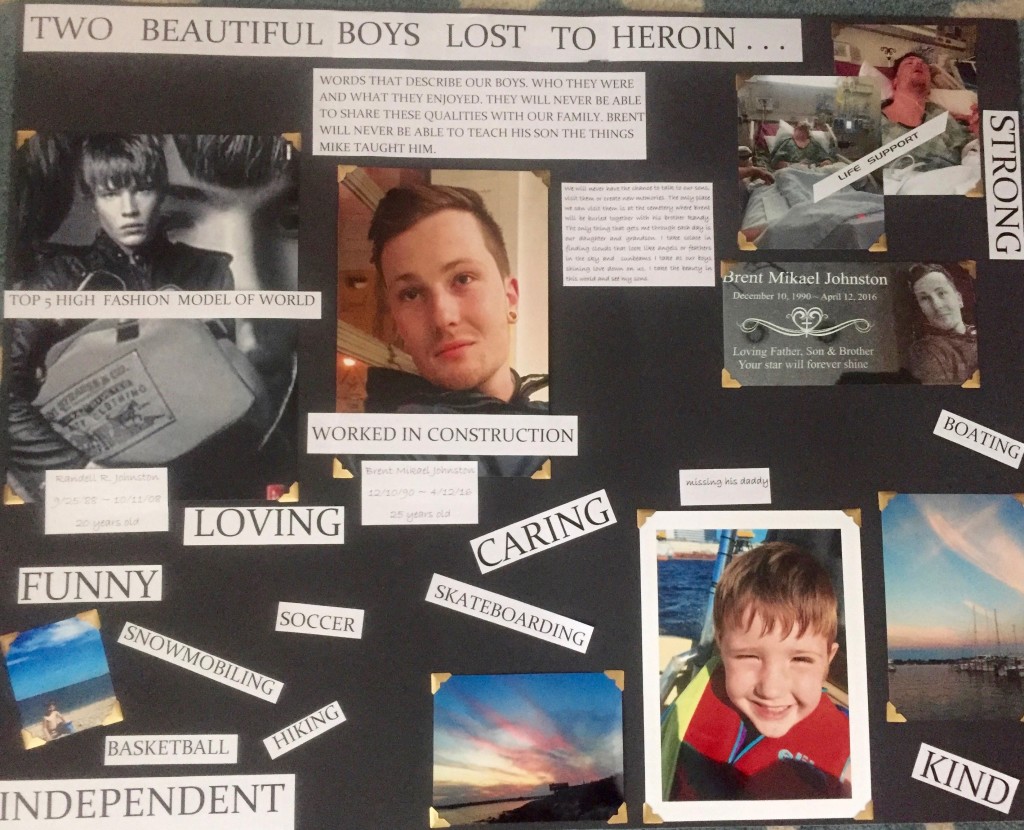

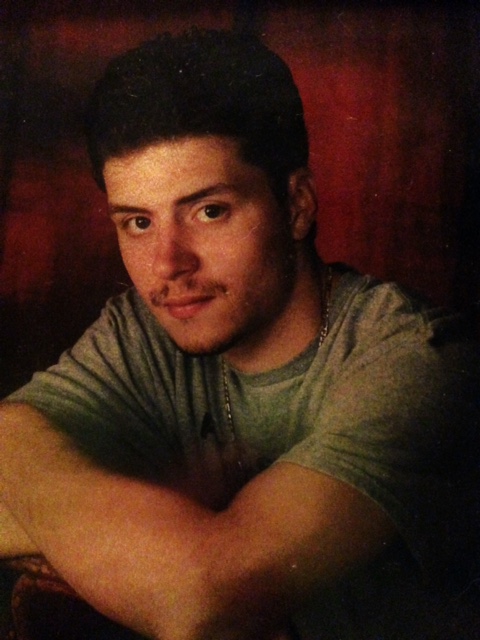

Heard, who lives in Waterford, was used to juggling her son’s addiction treatment. Brent had begun taking synthetic heroin when he was just 14, crushing it up and snorting it. Soon he started injecting it through an IV. At that time, Brent’s older brother Randy, a model with the Ford Models agency, was living in New York and also using heroin. The brothers had been in the same social circles at Waterford High School but never took the drug together. “They had that respect for each other,” Heard says. Most of their old cohort is gone now; since they graduated high school, about two of their friends have fatally overdosed each year.

The Connecticut Medical Examiner’s Office predicts 1,078 drug overdose deaths in the state this year, an eighteen percent increase from 2016.

Drug overdose is the leading cause of death for Americans under the age of 50. Last year alone, there were sixty thousand fatal drug overdoses, the majority of which involved opioids. It’s an epidemic that has ravaged communities across the country, from towns nestled in the Appalachian Mountains to cities along the Connecticut coast: Waterford, Bridgeport, New Haven. Although Connecticut ranks twenty-ninth in terms of state population, it has the eleventh highest opioid-related death rate in the country. And it’s only getting worse. The Connecticut Medical Examiner’s Office predicts 1,078 drug overdose deaths in the state this year, an eighteen percent increase from 2016.

Young adults between the ages of 18 and 25, who tend to be both emotionally and financially dependent on their parents, are the hardest-hit population in the opioid epidemic. In recognition of young peoples’ vulnerability to addiction, Connecticut has begun to shift its priorities. The state has poured $335 million into its substance abuse services, funneling state funding into in-home treatment, including “family therapy teams” that work with young people and their relatives on substance abuse issues. Doctors are now allowed to prescribe Narcan, an opioid antidote, more easily, and teens’ friends have legal immunity if they administer Narcan while themselves high or in possession of drugs.

But no amount of funding can fully alleviate the weight of suffering that the families of addicted people shoulder. In Heard’s court statement to the man sentenced for dealing the drugs that killed her son, she prayed that he change his life and offered forgiveness. “You are someone’s son,” she told him. “You have a mother.”

For families, addiction treatment isn’t just a one-time effort, but a circuitous process of decision-making and waiting. Many find the landscape of treatment options overwhelming to navigate, especially when programs are overcrowded or have prohibitively high costs. Some parents first reach out to those who have already struggled through a child’s addiction, relying on social networks like the one created by Community Speaks Out, an organization based in New London. Sometimes families can afford to send their child to a comprehensive, expensive long-term program like Turnbridge, a rehabilitation center on Orange Street in New Haven. But other families are largely absent from their children’s recovery processes, and those struggling with addiction find surrogate communities in places like Teen Challenge, a Christian recovery center located near New Haven Union Station.

—

No matter the route, addiction treatment is a complex process: doctors first recommend detox, then a thirty- or forty-five-day rehabilitation program, followed by a stay in a sober house or a safe, monitored environment. But families face difficulties at each stage. Health insurance doesn’t always cover addiction treatment and the dearth of regulated, affordable options creates a cycle of relapse for people recovering from addiction. If a person does complete a rehabilitation program—despite steep dropout rates—they are still far from recovery. Sober houses have high risks of relapse, as they are unregulated and generally have no security, bed checks, or visitor restrictions.

Three New London County mothers have recently stepped in to guide other families through the throes of addiction and substance abuse treatment. In 2015, Tammy de la Cruz, Linda Labbe, and Lisa Cote Johns founded Community Speaks Out, an organization aimed at helping families navigate treatment options. It was a struggle that the other mothers knew all too well—each of their families, too, had been touched in some way by addiction.

The group formed when de la Cruz’s son, Joey Gingerella, started speaking at local high schools about his battle with addiction. Joey died last December, not from a needle but from a bullet. He was killed outside a Groton bar when he intervened to stop a man from beating his girlfriend. The three mothers persevered through this tragedy, continuing their mission to support affected families and increase awareness of addiction prevention programs. So far, they have reached communities all over Connecticut and have helped over two hundred people enter rehabilitation programs.

“We become family,”…It’s a bond that no one wants to have to share, but one that becomes an essential lifeline during periods of familial conflict or grief.

Their organization offers assistance with every part of their clients’ needs. In addition to working day jobs, the three women manage support groups, conventions, and legislative initiatives, and help clients navigate insurance coverage. Their work with recovering addicts is tireless—and uncompensated. “If someone wants to go to rehabilitation,” Cote Johns says, “we get them in.”

Community Speaks Out absorbs new (non-paying) clients into a network of sympathy and encouragement, and the women stay in constant contact with them. Cote Johns doesn’t hesitate to shoulder other families’ heartaches; it’s part of the job, she says. She has called one mother twice a week for the past year to check in on her children. “We become family,” Cote Johns sighed. It’s a bond that no one wants to have to share, but one that becomes an essential lifeline during periods of familial conflict or grief.

This past January, Community Speaks Out received major recognition for its work: a five thousand dollar grant from Lawrence + Memorial Hospital in New London, an affiliate of Yale-New Haven Hospital. Through the grant, Community Speaks Out will become Connecticut’s first designated certifier of sober houses. After undergoing training in March with the Massachusetts Alliance for Sober Housing, de la Cruz, Labbe, and Cote Johns called up every New London sober house, inviting each to register with the organization. So far, six have registered. Their regulation requires consistent safeguards like curfew check-ins, visitor regulations, Narcan availability, and training. The group is starting in New London, but hopes to expand across Connecticut to cities like New Haven.

The need to regulate sober houses is a personal one for Cote Johns. The year her son Christopher died, he was 33, hoping to get back on his feet after a thirteen-year battle with addiction and six months in jail for violating probation. He had become hooked on drugs after taking prescription pain medications for routine surgeries in high school. On the day Christopher was released from jail, he had been sober for almost eight months. One of Cote Johns’s friends picked him up and took him to a rehabilitation center, but all the beds were full.

For recovering addicts, finding an available spot in a rehab center after a detox program can be extremely challenging. Cote Johns estimates that nine out of the ten times she calls a center, all the beds are full. In theory, New Haven has fifteen “Substance Abuse Care Facilities,” but that number includes only a couple of dedicated rehab centers.

Since Christopher had already detoxed on his own and had to wait on rehabilitation, he and Cote Johns’ friend drove directly to a sober house in New London. There are thirty sober houses in New London; New Haven has thirty-three. None are registered and few have any regulations. Though they are supposed to be safe places for people to recover from addiction, in reality, anyone can walk in and hand drugs to the residents. Christopher had stayed at many sober houses, and at every one of them, people were taking drugs.

The first few months of sobriety, when recovering addicts transition from detox to rehabilitation, are a critical window in the recovery process. In this period, they experience the physical effects of opioid withdrawal—anxiety, nausea, and vomiting—while learning to cope with stress without drugs. Many are tempted to start using again when cravings are intense and supervision is not. Those first few months are also when most fatal overdoses occur. People fresh out of detox may not realize their tolerance has dropped, so a once-routine dose can kill them.

Christopher knew detox programs didn’t work. He told Cote Johns, “We need to fix ourselves from the inside. I have to change this, Mom.”

But Christopher wasn’t able to save himself, and Cote Johns couldn’t save him, either. He died while living in a sober house and waiting for a spot in a rehabilitation program. One of his friends had walked in and given him the drugs that would kill him. One of Cote Johns’ friends found Christopher’s body the next day, after kicking down the door of his room.

Two years ago, Karine Heard, Brent’s mother, met Cote Johns at a forum for parents of children with addiction at Montville High School in Oakdale, Connecticut. The two women immediately bonded over their experiences with their sons. Brent was still alive at the time, but Cote Johns’s son Christopher had died in 2014 and Heard had already lost Randy. In the years since, the two have remained close, sharing memories and moments of solace: Cote Johns will call up Heard and say, “Let’s go light lanterns.” They’ll spend the evening on the deck of Cote Johns’s house in Groton, talking about their sons. For Cote Johns, losing a child to addiction is “a different kind of pain, because you feel like you failed as a parent, as a mom.”

Last January, sipping tea in a Panera Bread in Waterford, Heard recounts what happened to her sons in a soft voice. It’s not an easy story to tell. She shifts uncomfortably in her navy sweatshirt and rests a well-manicured hand nervously on her neck. When Brent was almost 18, 20-year-old Randy overdosed and died, she says. “Brent—he just couldn’t live with the fact that his brother was gone,” Heard says. “It was too much for him.” Brent’s drug use grew worse, he dropped out of high school, and that year he cycled through thirty-day rehabilitation programs in New Haven. Heard tried to give him the support and resources he needed, but it wasn’t enough.

—

For a client with private health insurance, Community Speaks Out could make a call to Turnbridge, a long-term rehabilitation center in New Haven, located on Orange Street near the New Haven Green. Turnbridge does not accept Connecticut’s public insurance, Husky, and it is out of network for most private insurance plans, meaning that copays are high. Turnbridge would not confirm its fees, but most thirty-day programs like it are forty thousand dollars. It’s a price tag that some, like Cote Johns, believe is far too high.

But at Turnbridge (formerly called ‘Turning Point’) clients aren’t pushed out after any set period of time. Lauren Springer, the center’s Family Liaison, believes the open timeline ensures that each participant heals completely and leaves only when he or she is ready. No one can say for sure how long a broken bone will take to heal, and some say the same is true for addiction. While the detox phase is usually six weeks, according to Springer, some clients stay for over nine months.

At Turnbridge, the clients live in a large, classically New England stone house, surrounded by well-tended bushes and a lush green lawn. The website boasts a basketball court, gym, and art room. In Springer’s office on Orange Street, where the students come during the day for meetings and treatment, Oriental rugs pattern the gray wood floors and candy is displayed on the desk.

A stay at Turnbridge has three phases, the first of which usually lasts six weeks and helps clients detox and come back to a healthy baseline. Exercise, healthy eating, and family meetings are all part of the process. In addition to his or her own family’s support, each client has a case manager, a therapist, a sponsor, a psychiatric APRN licensed to prescribe, a program director, a family liaison, and a family therapist. By the third phase, clients have much more freedom: they can take the bus to jobs in downtown New Haven and have less frequent appointments at the Turnbridge offices on Orange Street.

Like Cote Johns, Springer entered the world of addiction treatment support as a mother suffering through her son’s addiction. When she first started attending Narcotics Anonymous and Alcoholics Anonymous support groups, she was terrified. “My son’s not like those people,” she thought. But when she found that the groups helped her heal, she started a group just for parents, for which she still commutes to New Jersey to run. Later, she joined Turnbridge, where she helps families become “part of the team,” as she likes to say.

Turnbridge, which accepts clients between the ages of 18 and 26, needs the support of parents. Springer tries to help each family come to terms with its child’s illness. Sometimes parents are the first ones to call for help, but they need Springer to give them the confidence to tell their children that coming to New Haven for treatment is the only option. Other times, parents will deny that a problem exists, insisting, for example, “When I was in college, I smoked a lot of weed, and I did fine,” Springer says. But the most common issue is parents enabling their children’s continued drug use.

“No one wants to make a change until it’s just too uncomfortable where they are,” Springer says. She knows firsthand how hard it is, as a parent, to give your child unconditional love and support while not facilitating their addictive behaviors. Her son, who was once at Turnbridge but left in the middle of the program, is still using drugs. She admits that she doesn’t know where he is right now. “I will pay for treatment, I will visit him when he’s in treatment, I will do whatever I can while staying on my side of the fence,” she says. The current situation “breaks her heart,” but she knows she can only do so much to guide and protect him.

—

Manny Barreto decided to change his life when he woke up from life support, his face wet with his aunt’s tears. It was the first time he had ever overdosed. At the time, Barreto was a 28-year-old manufacturing marketer in Brooklyn, New York. He had started doing molly, which contains the drug MDMA, years before. But when his drug dealer ran into trouble in the neighborhood, he switched to pure MDMA, and then to Ecstasy.

The evening he overdosed, he drank alcohol, smoked weed, and took five different kinds of Ecstasy pills. The high hit all at once, and he stumbled downstairs to a friend’s apartment to ask for help before passing out. Though he faded in and out of consciousness in the ambulance, he remembers lying on the cot, wearing a wife beater in January, thinking, “This is the totality of my existence on the planet? I’m gonna die a drug addict in the back of an ambulance?”

Now a big-boned man with a dark mess of curls, glasses, and a black beard that widens with his grin, Barreto jokes that back then, he looked shriveled up, like a “turtle without its shell.”

Barreto’s life was changed by Teen Challenge, a global Christian ministry that has a recovery house in New Haven, among other branches across the world. The New Haven outpost is located in a group of run-down wooden houses clustered on Spring Street, near New Haven-Union Station and just a mile away from Turnbridge. Strictly speaking, it’s neither a rehabilitation center nor a homeless shelter, but there are beds, a shared kitchen, and sitting areas where the men discuss Bible passages. The organization opens its doors to anyone who wants to get closer to God, but most of the participants struggle with addiction, too. The New Haven location is only for men over the ages of 18, but Teen Challenge New England has three women’s homes, and there are branches on almost every continent of the world. “We run out of beds, we’ll get a sleeping bag for you,” Barreto says.

After Barreto’s mother became abusive, he was adopted by his aunt and uncle, both of whom are ministers. Growing up, he knew about Teen Challenge’s ministry work, and the organization visited their church from time to time. So, when his aunt pulled back the curtain in the emergency room and said, “Are you ready to go to Teen Challenge?” Barreto was too tired to refuse. Leaving everything behind in Brooklyn, he enrolled at the New Haven location in 2012 and has been there ever since, first as a client and now as a staff member.

In many ways, the fifteen-month program is similar to other long-term rehabilitation programs like Turnbridge. It has four phases, each one emphasizing personal discipline, healing from the inside, and making plans for a healthy future. There are chores, mentors, and, in the last phase, job opportunities.

But the programs differ in terms of how they approach family involvement. At Teen Challenge, men are cut off from their families and friends in order to avoid the temptation to return to their old lives. Barreto is no longer in touch with anyone he used to use drugs with; almost all of those people have already died. At Turnbridge, parents and families are integral parts of the healing process and receive training in how to support loved ones with addictions. Unlike the widespread support network at Turnbridge, Teen Challenge’s clients meet with a single mentor. Teen Challenge is unafraid to discipline men who relapse or disrespect authority, whereas Turnbridge treats relapse or behavioral issues with therapy and more time in the program. If someone smokes or talks back to a staff member at Teen Challenge, he will be set back in the program’s phases and given more chores. At Turnbridge last month, young men were vaping on the sidewalk.

The two programs also differ in the demographics of their clientele. While the opioid epidemic more broadly skews white—80 percent of drug overdose deaths in Connecticut this year have involved white people—in New Haven, where there are significant Black and Hispanic populations, the epidemic crosses racial lines. Every client I saw in the hallways or outside at Turnbridge was white. At Teen Challenge, a car of Black men pulled out of the driveway and waved to me as they headed to their jobs in town. Turnbridge, which takes only private insurance for medical fees, also has residential fees that are around nine thousand dollars a month. At Teen Challenge, participants are asked to give what they can, but it’s unusual that they can pay the fees in full: $750 per month, plus a $750 intake fee. Many men come for free. And there are no medical bills, as no doctors work in the Teen Challenge house.

Comparing the success of the two programs is difficult. In 2017, Turnbridge published an outcome study reporting that 70 percent of all of its clients reach one year of sobriety and 80 percent of that group complete another year. These numbers are striking compared to the national average; the National Center on Addiction and Substance estimates that only 30 percent of all people who complete a rehab program are successful. But addiction is a life-long struggle, and Turnbridge clients could easily relapse after two years. The most recent numbers on Teen Challenge are from a 1999 dissertation at Northwestern, in which a political science graduate student found that 86 percent of clients were drug-free after three years, and, perhaps most strikingly, 91 percent were employed.

In the first part of the program at Teen Challenge, men detox without drugs to wean them off heroin. Barreto says that opioid-based detox clinics that use drugs like methadone, a synthetic opioid, don’t solve addiction; they just substitute one form of it for another. After all, he asks, what’s the point of getting clean? To “experience life.” He’s seen men come to the program because, even after ten years, they couldn’t kick their methadone addiction. The first thing Barreto tells incoming men is to accept the fact that, whatever their addiction, it will tempt them to leave. When their cravings start to push them toward the door, they have Barreto’s phone number and are told to call if he is not in his office. At private-pay rehabilitation centers, Barreto says, the staff clocks out at 5 p.m. They call it “boundaries,” he scoffs.

Barreto knows how hard it can be to resist the temptation of leaving. But he was sustained by the other men in the program, like his now-colleague Steve Stokes, the program supervisor, who was six months into the program when Barreto first arrived. Unlike Barreto, when Stokes came to the program, he had already been in and out of rehabilitation for more than ten years. In a thick Boston accent, he describes how it started when he began drinking to the point of blacking out at the age of 13. He started self-medicating to deal with his Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD). To add to his stress, his mother was abusive and cheated on her Stokes’s father with his uncle, at which point Stokes’s father left. Stokes’s OCD resulted in powerful hallucinations that he experienced throughout his youth. When he was ten, he says, he was taking a test when a voice in his head warned him, “If you don’t get up and walk over to the chalkboard and break that piece of chalk right now, your dad’s gonna get into a car accident.” He got up, broke the chalk, and was kicked out of the classroom.

Stokes’s OCD was treated by doctors at McClean Hospital OCD Institute in Boston, where he was prescribed Klonopin. But he began abusing the medication and using it alongside heroin. Klonopin makes a heroin overdose more likely. In addition to his drug use, Stokes’s anger problems, which he thinks developed as a result of his abusive household, led him to crime and gangs. By the time he was 22, he had overdosed ten times. When he wasn’t in the hospital or a thirty-day program, he was washing his clothes in puddles and living in his car. Stokes’s dad tried to stay in his life, but after Stokes overdosed twice, he kicked him out of the house. “I can’t have you dying here on this couch,” his dad told him.

Stokes’s hands, wrapped in tattoos, start to fidget as he goes through his story. As he recounts his last overdose, he pauses to wipe tears from his eyes. He had been on a sleepless four-day binge on speed and heroin, he says. His friend, a woman who has since died from an overdose, lured him into her car with drugs. She took him to the hospital where he protested for three hours in the parking lot, tearing her car apart and threatening to kill her if she made him go inside. She finally convinced him and, after doctors strapped him down, he woke up to his dad pleading with him to go to Teen Challenge. “I’ll try,” he said, knowing that he had nothing to lose.

Like Springer, Barreto insists that addiction cannot be isolated to a single source. “We understand that it’s no longer just biological, just psychological, just sociological,” he says. He acknowledges that not everyone who tries drugs becomes addicted. Teen Challenge does not wish to punish people addicted to drugs for their “injury,” as Barreto calls it, but the approach does “use biblical principles to correct some of their character flaws.” A person with an addiction is a slave to his own desires, contradicting the Apostle Paul, who taught, “I will be a slave to nothing except Christ,” explains Barreto.

Hoping to one day operate out of a safer location than the current outpost on Spring Street, the Connecticut branch of Teen Challenge is raising money by renovating condominiums it was gifted. The men in the house, alongside local church groups, provide the labor, and the leases or sales of the condos will provide funds for the organization. Barreto envisions a large house in the countryside, akin to something like the Turnbridge mansion.

—

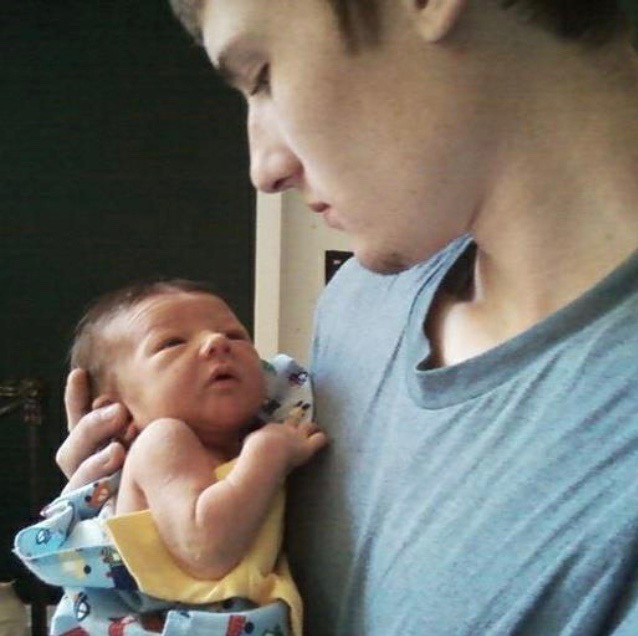

When Karine Heard talks about her younger son, Brent, she still slips into present tense: “My son tells me,” or, “Brent likes…” She struggled with him constantly throughout his adolescence—from the age of 14, she says, he seemed stuck in a revolving door of addiction treatment, homelessness, jail, even life support. His parents tried tough love, enabling, and everything inbetween. She left food for him in the outside fridge or drove him where he needed to go just to avoid giving him cash.

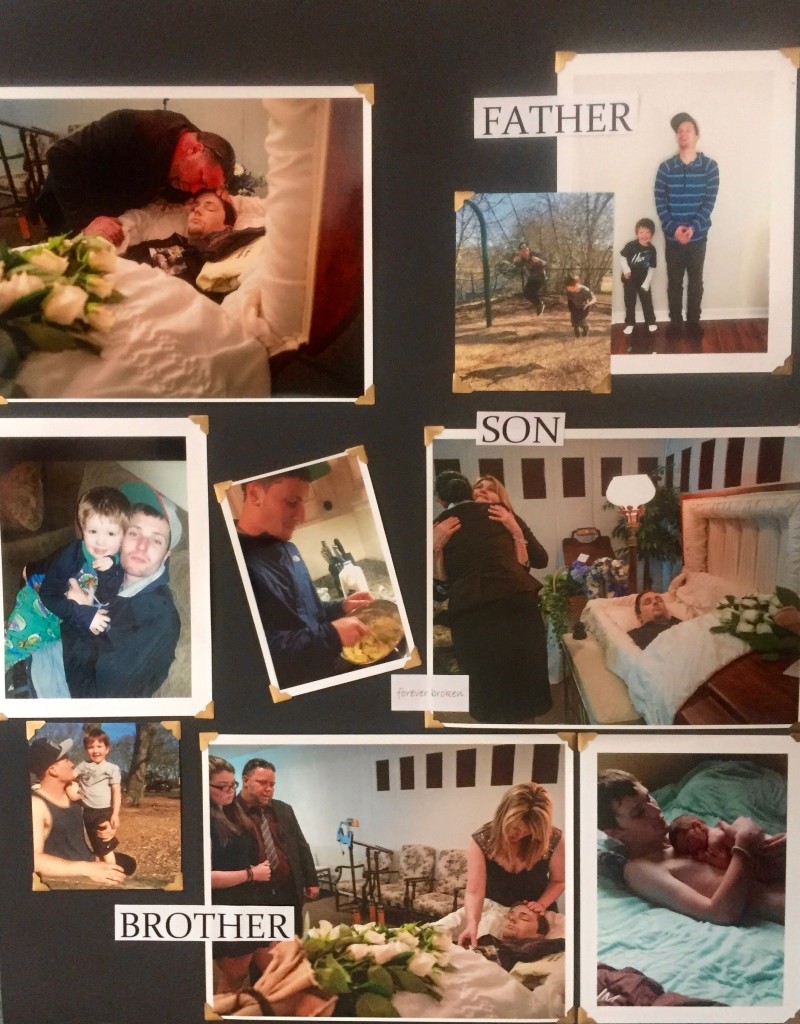

But there was only so much of Brent’s life that she could control. On April 12, 2016, shortly after he called his mother to ask for a piece of mail, he made another call, to his acquaintance Timothy Paprocki, to ask him for drugs. Later that day, Brent overdosed on fentanyl-laced heroin in Paprocki’s car in Groton. Paprocki didn’t call for help. Emergency Medical Services found Brent some time later and transported him to the hospital, where he was pronounced dead upon arrival.

Heard got the call from the Lawrence + Memorial emergency room at 8:30 that night. She knew the number by heart. When the nurse on the phone asked Heard to come meet the doctor, Heard started screaming, “No! No! No!” The woman replied, “Please drive safely,” and Heard threw the phone across the floor.

Heard was sure that Brent was dead. “Karine, you don’t know that,” her husband reassured her. Maybe he’d had a heart attack, he said. Maybe he was okay. As they pulled up to the hospital, they passed an ambulance leaving. Then a police car and another ambulance and another police car. EMTs watched the parents walk in. The doctor looked at them in the hallway and said, “I’m so sorry.” She told them the story, but Heard already knew it.