In late September, Yale’s clerical and technical workers won a new labor contract. But Yale continues to subcontract much of its library work to non-union workers.

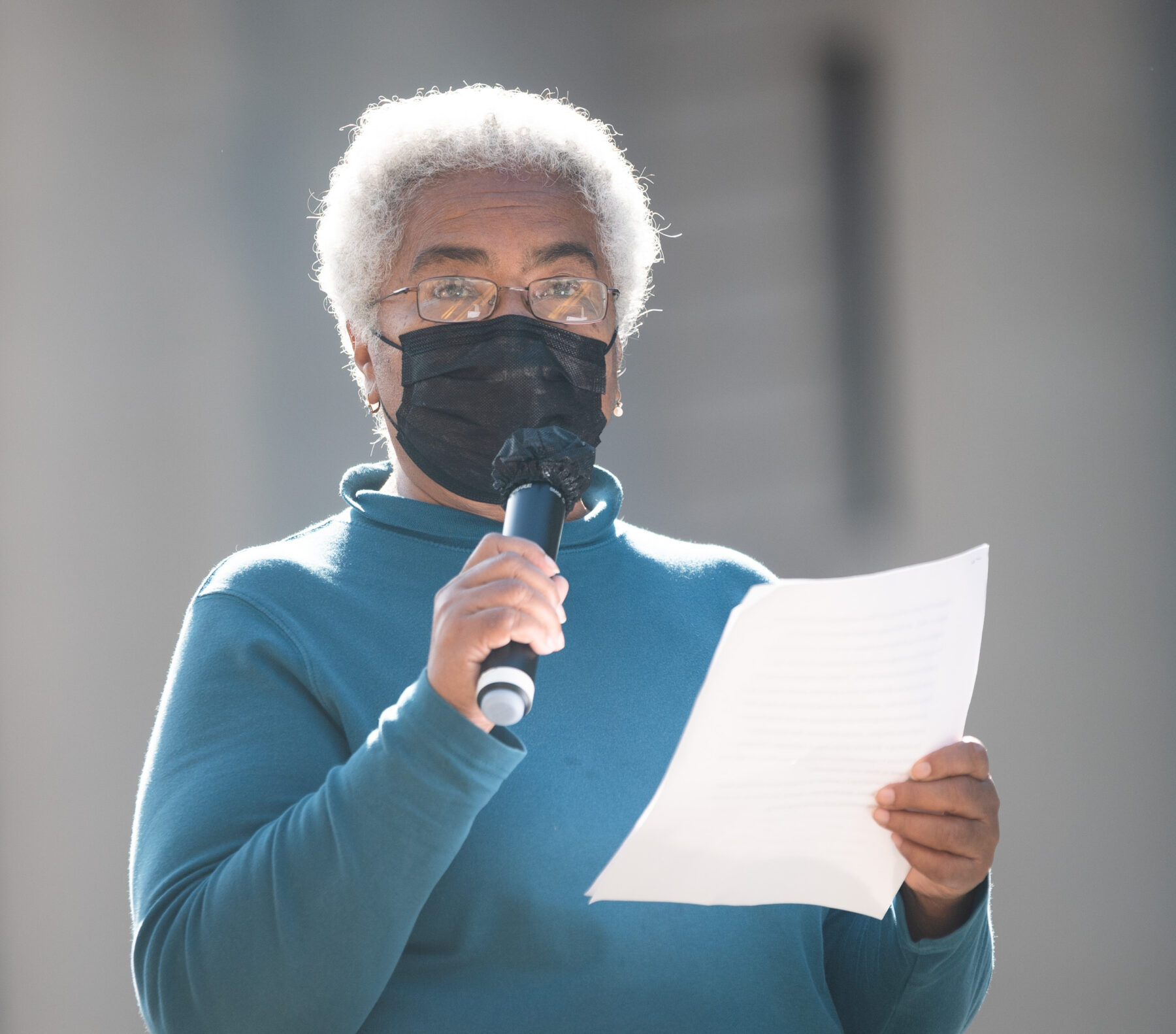

“I hope they hear me,” shouted former New Haven alderwoman and longtime Beinecke Library employee Dolores Colon ’91. She gestured behind her to the colonnaded façade of the newly-renamed Schwarzman Center, where Yale President Peter Salovey was busy emceeing the kickoff of Yale’s seven billion dollar “For Humanity” capital campaign, the largest in its history. Colon’s voice, amplified by microphone, echoed across the intersection of Prospect and Grove: “It’s time for the leaders of Yale to respect their workers, and to respect their community.” The crowd—a two hundred-strong mix of Yale workers, students, community organizers and local politicians—whooped and hollered.

Colon was the penultimate speaker at the October 2nd event, a rally held by New Haven Rising, a community organization formed in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis to combat state budget austerity and the evaporation of good jobs. That the event overlapped with Yale’s capital campaign kickoff was no coincidence. At the rally, attendees brandished signs with the question “What should Yale be for?”—a direct response to the administration’s email announcing the fundraising bonanza, which had asked its recipients, “What are you for?”

At the October 2nd rally, attendees brandished signs asking “What should Yale be for?”, a response to the University’s recently announced $7 billion capital campaign, titled “What are you for?” PHOTOGRAPHY BY LUKAS FLIPPO.

The mood on Prospect Street, where upbeat music and dancing alternated with remonstrative chanting and searing jeremiads, was by turns euphoric and indignant. For Locals 34 and 35 UNITE HERE, the unions representing the university clerical and technical (C&T) workers and service workers, respectively, there was much to celebrate. Earlier that week, Yale and the unions announced that they had reached a tentative agreement for five-year contracts that included unprecedented job security provisions and created a pipeline that would give New Haven residents an additional forty jobs per year, half of which would be full-time positions with union wages and benefits.

The contracts, which were ratified by both unions on October 20th, capped an acrimonious sixteen months of negotiations. At a New Haven Rising rally at the same intersection in early May, Local 35 Chief Steward and New Haven Board of Alders President Tyisha Walker-Myers had given the University a stern ultimatum: “Either [Yale] deliver[s] fair contracts, or we’re gonna shut this city down.” Given the unions’ power on the Board of Alders—since 2011, pro-labor candidates have dominated the city’s legislative body—this was no empty threat.

Yet many of the speakers that October afternoon painted a darker portrait of the state of the city, still reeling from the effects of the pandemic, where a quarter of residents live below the poverty line and one in three adults in its lowest income neighborhoods routinely goes hungry. Nearly every speech connected New Haven’s chronically underfunded schools and threadbare social services to the $157 million tax break New Haven bestows upon the University and Yale New Haven Hospital. Many also castigated Yale for failing to fulfill its 2015 agreement to hire a thousand New Haven residents into full-time, permanent jobs, with half of those hired coming from “neighborhoods of need.” The deadline for that hiring commitment—which Yale agreed to only after city organizers held its feet to the fire—came and went in April 2019. While Yale says that it fulfilled its promises, New Haven Rising organizers argue that the university intentionally inflated its job numbers by including temporary postdoctoral associates and journeyman construction workers. “We need better hiring opportunities right now,” Remidy Shareef, an organizer with Ice the Beef, a local youth organization working to stop gun violence, told the crowd. “If Yale treats the community with this little regard, how do donors believe that a donation to Yale is a donation to humanity?” Shareef said, referencing the title of Yale’s capital campaign. Yale, speaker after speaker insisted, needed to step up.

Colon echoed these arguments at the October rally, but she had also come to Prospect and Grove to raise a more specific issue. In 2019, Beinecke administrators had initiated a plan to start subcontracting some of the library’s cataloguing and processing work instead of hiring union employees to do it, she told the crowd. “Our collections are being loaded onto trucks and being shipped to Pennsylvania, where they are being processed by workers hired for as little as thirteen dollars and fifty cents,” Colon said, her last few words drowned out by boos and jeers. “I can’t believe it either,” she pressed on, shaking her head. “It’s a lot less than what Amazon warehouse workers make per hour. It’s just shameful.”

In its recent history, Yale has been no stranger to subcontracting, a labor practice in which a company hires an outside firm instead of directly employing workers itself. Yale’s insistence on its right to subcontract was the central issue of the 1996 contract negotiations, which culminated in two bitter monthlong strikes. In the midst of those negotiations, American historian Robin D.G. Kelley wrote that university subcontracting “has been part of a larger corporate strategy to reduce wages and benefits and to bring in casualized, temporary nonunion labor”—a strategy, he argued, which let “the administration off the hook by rendering even more invisible the exploitation of labor at the university.” A quarter-century later, Colon was there to make sure no one would look away.

“People in New Haven neighborhoods know that if they do get a job here and get a foot in the door, they can have good benefits for their children and themselves,” she said. As a single mother with two young children, Colon was speaking from personal experience; she couldn’t make ends meet until she began working at Yale. “Instead of shipping jobs out of state, Yale should be honoring their commitments to hire from neighborhoods of need into good jobs,” she said. “Will they continue to spend millions on out-of-state firms? Or will they invest money in their own community, here in New Haven?”

Former New Haven alderwoman and longtime Beinecke employee Dolores Colon ’91 speaks to a crowd of two hundred at an October 2nd rally on Prospect Street. PHOTOGRAPHY BY LUKAS FLIPPO.

—

The morning after the rally, I drove twenty minutes south of Yale to Ocean Avenue, a winding street that snakes along the beaches of West Haven’s coastline, between the mouths of Cove River to the north and Oyster River to the south. The houses on Ocean Avenue are two-story, single-family dwellings with modest front yards and spectacular views of the Long Island Sound. I knew immediately which house I was looking for when I saw a flash of red on the door: a “Yale: Respect New Haven” sign, just like the ones that have dotted the campus and city for years. After knocking on the door, careful to avoid disturbing the sign, I was ushered inside by my host.

Even if you had no idea what she does for a living, you could tell pretty quickly that Amelia Prostano is a librarian, and an extremely fastidious one at that. Open on her kitchen table in anticipation of my arrival was a photo album, dozens of pages long and meticulously organized, covering Prostano’s nearly forty years as a member of Local 34 and an employee at the Beinecke, where she currently works as an acquisitions assistant. While she fixed me a coffee, I flipped through page after page filled with photographs of picket lines, marches, rallies, and the odd busload of cops dispatched to intimidate striking workers. In her four decades at Yale, Prostano’s personal archive of Yale’s labor activity certainly hasn’t lacked material. “Unionbusting,” the New York University historian Kim Philips-Fein once wrote in The Nation, “is as much a Yale tradition as Lux et Veritas.”

Prostano came to Yale in 1983, during the crucible of one of the fiercest anti-union campaigns in Yale’s history—and one of the most consequential moments of labor struggle in late twentieth century U.S. history. In the decades before the nineteen eighties, national labor organizers had tried and failed multiple times to unionize Yale’s clerical and technical employees, a workforce largely made up of female secretaries, librarians, and laboratory technicians. In May 1983, following a three-year organizing drive spearheaded by the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees International Union (HERE), a slim majority of Yale’s 2,600 C&T employees voted to unionize as Local 34. After a year of trying and failing to negotiate a contract with a hostile administration, the fledgling union went on strike in late September 1984.

At a moment when the archetypal union worker in the American imagination was a white, male factory worker, Local 34’s campaign was notable for being avowedly feminist in both its makeup and its demands. Prostano, who earned just $9600 during her first year at the library, remembers a casual conversation just a few weeks into her job in which her supervisor commented on how nice it was that she had the chance to make “pin money.” An expression dating back to the seventeenth century, “pin money” denoted the allowance a man would give a woman to purchase clothing and other incidentals. “I thought to myself, I’m working a full-time job, and you’re telling me it’s nice to have pin money?” Prostano told me. “But that’s where we were in 1983.”

Prostano was there in early October 1984, when nearly 200 C&T workers were arrested during a silent protest in front of then-Yale President Bartlett Giamatti’s house. And she was there three weeks later, when civil rights leader Ralph Abernathy blessed the striking workers in a packed United Methodist Church on the New Haven Green before they went out to a protest in front of Woodbridge Hall. “Yale is a great institution. Yale is a wealthy institution. But Yale is treating certain segments of its population unjustly and Yale University ought to be ashamed,” Abernathy, one of the late Martin Luther King Jr.’s closest friends and advisors, told the crowd. “You have the opportunity to witness for justice and equality. . . for a grand and noble cause.”

“There was no way you could have stopped us in 1984,” Prostano told me. “It’s a feeling I can’t even explain. It was life-changing. It changed my life in so many ways.”

The union emerged victorious from the strike, winning a contract that went a significant way toward eliminating the gender pay gap at Yale and provided benefits tailored to the needs of women workers. When Prostano lost her husband in 1995, it was only because of her union job and the raises she knew were coming that she was able to keep her house on Ocean Avenue, where, a quarter century later, she weathered the pandemic with her two young grandchildren.

The 1984 strike wasn’t just life-changing for Prostano. For many labor historians, it holds a special place in recent U.S. labor history. Local 34’s ability to win substantial concessions from the university was a rare bright spot for the U.S. labor movement in the nineteen eighties, which faced a presidential administration hell-bent on union-busting and an economy hemorrhaging industrial jobs. (In New Haven, the vaunted Winchester Arms factory, once the largest employer in the city, shuttered its doors in 1977.)

The strikers also pioneered a social-movement style, democratic approach to labor organizing that has become a model for successful campaigns in recent years. Instead of centering their campaign around wages and benefits, the 1984 strikers focused more on dignity and social justice, a strategy which gave them a broader base of support. Their aim was to expose the Yale administration’s hypocrisy and harm the University’s brand, its most important asset. In that sense, the strikers were acting with oracular foresight. “What Local 34 figured out in 1984 presaged our current moment in the economy, when attacking a companies’ brand is what you do to build power,” Jacob Remes ’02, a labor historian at NYU working on a book about the 1984 strike, told me. Throughout the fall of 1984, union members carried signs claiming that they were “On Strike for Respect,” a rhetorical flourish that echoes across four decades of New Haven labor history and reappears in the New Haven Rising slogan, “Yale: Respect New Haven.”

The strike and its most memorable slogan even inspired its own book, On Strike for Respect, published by three labor historians and one lawyer in 1995. While the book’s sales only reached a couple thousand, Prostano, true to her profession, has a good-as-new copy, which she kindly offered me later that afternoon on my way out the door.

—

But I hadn’t come to Prostano’s house just to talk history. And I wasn’t her only guest. A few minutes after I arrived, Jennifer Garcia and Cecillia Chu walked through the door—Prostano’s colleagues at the Beinecke and fellow members of Local 34, where Garcia serves on the executive board. I was there to learn more about the library’s use of subcontracted rather than union labor, a problem which goes back years, as all three of them explained.

Garcia was hired by the Beinecke as an archives assistant in May 2013. At the time, the library was in the midst of what it called the “Baseline Processing Project.” The initiative was a response to the growing mismatch between the library’s steadily-growing mass of acquired materials—a product of its robust budget—and the amount of people it employed to do the cataloguing and archiving work necessary to make those materials accessible to teachers and researchers. As part of the project, two temporary employees had been hired to help Garcia and the other two archives assistants in the manuscript unit. Within two years, however, the two other permanent archives assistants had left the unit, and when the temporary positions expired, the library didn’t extend their duration or hire the workers into either of the two permanent positions that had opened up.

“For the next two years, I was the only person providing support on the processing end of the department, which was a lot, and very difficult,” Garcia said, especially as the collections kept growing and the backlog problem remained unsolved. “Beinecke is really wonderful, and has robust budgets for developing its collections. But in many ways it’s been frustrating to see that the same emphasis they have on enhancing what we have in-house doesn’t seem to apply to the employees that work there.”

In late March 2019, Prostano and Garcia, who serve as union stewards in the department, were called into a meeting with the then-head of Beinecke Technical Services and one of Yale’s financial analysts, who matter-of-factly explained that the library—at the behest of the Provost—was planning on hiring subcontractors to help deal with the ongoing backlog problem. Both Prostano and Garcia were completely blind-sided by the news. Later, they discovered that the Beinecke had signed multi-year contracts with two companies: Backstage Library Works and the Winthrop Corporation, based in Utah and New York, respectively (Backstage operates the Bethlehem, PA warehouse that Colon mentioned in her October 2nd speech). The contracts were each worth millions of dollars. “I was shocked,” Prostano said. When union members dug through Backstage’s website, they discovered that it was advertising processing positions for half of what a Local 34 worker would normally make.

Once Prostano and Garcia learned about the subcontracting project, they sprang into action, holding a series of employee participation meetings to inform the other union members at the Beinecke about the project and to start pushing back. “Bad management decisions often become a really good organizing impetus for us,” Garcia said. “It was a really unifying thing to watch the union members, first in technical services at the Beinecke and then at the Beinecke as a whole, rally together to push on management to respect our work and the library.” After months of pressure, the library offered a partial concession and created four new temporary positions to help with the backlog. But the multimillion dollar contracts—and the potential local jobs they represented—remained.

What made the 2019 subcontracting issue particularly troubling for the union was that its announcement came just months after the deadline for Yale’s hiring agreement had passed. It seemed like a pointed refusal to hire local residents for union jobs, even though Yale needed the workers. That anger grew during the pandemic, when many New Haven residents who lacked stable employment struggled to pay rent and put food on the table.

“The beautiful thing about belonging to a labor movement is that your interest is not just in making life better for people who are part of the union, but also to make that ripple outward to the communities that are negatively impacted by a large employer,” Garcia told me. “If Yale, instead of shipping our jobs out, really wants to make a positive impact on its community, then hire us. Hire people from New Haven. Be a better neighbor. There’s a real opportunity here, not just to push for respect for people who are already Yale employees, but for the entire community as well.”

Throughout the past sixteen months of contract negotiations, “Secure Jobs, Stable Retirement, Strong Community” has been Local 34’s main slogan.

—

Toward the end of their generally glowing appraisal of the 1984 strike, the authors of On Strike for Respect offered a single reservation: the strikers, they argued, hadn’t generally made a major issue of “Yale’s dominant position in the city of New Haven—and the contrast between the University’s wealth and the city’s poverty.” They warned that failing to do so in the future courted the possibility “that unions within universities can become as insular as the institutions in which they organize.”

Yale’s dominance over New Haven was a central theme of the October 2nd rally, but at no point was it more poignantly rendered than in the afternoon’s final speech. After Colon finished speaking, she handed the microphone to Davarian Baldwin, a cultural critic and professor at Trinity College whose most recent book, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities Are Plundering Our Cities, had exposed what labor economist Gordon Lafer once called the “tension between the enlightened promise and self-interested practice of urban universities.” Sporting a black tracksuit, black sneakers, and tinted Ray Bans, Baldwin paced back and forth across Prospect Street, his thundering voice rising above early-fall gusts of wind. “When I want to make people understand higher education’s growing control over the economic development and the urban governance of our cities and towns,” Baldwin boomed, “there’s no better place to talk about than Yale and New Haven. This is ground zero.”

Professor Davarian Baldwin, an academic at Trinity College and the author of In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities are Plundering Our Cities, caps off the rally. “Whether you know it or not, this campaign, this struggle, these conditions, place New Haven at the dynamic epicenter of a nation-wide battle being waged between profit and the people,” Baldwin said. PHOTOGRAPHY BY LUKAS FLIPPO.

But Baldwin considers Yale and New Haven “ground zero” not only because of the problems it so acutely represents, but also because of the forms of resistance that have emerged in response to them. From the 2001 founding of the Connecticut Center for a New Economy (which became New Haven Rising in 2012), to the unions’ 2011 takeover of the Board of Alders, to the recent pushes for local hiring and for Yale to pay local taxes, the movements that have developed over the past several decades show how “intimately connected” the relationship between labor and the community has become in New Haven, Baldwin told me a week after his speech. Looking back over the past four decades, the fears of the authors of On Strike for Respect never materialized; indeed, the opposite has largely been true. That library workers demanding an end to subcontracting are making common cause with grassroots social movements pushing the university to fundamentally transform its relationship with the city is evidence of how far things have come.

Three-and-a-half weeks after the rally, at noon on a rainy Tuesday, a group of several dozen Local 34 members marched into the cavernous lobby of the Provost’s office at 2 Whitney Avenue. They were there to present the Provost —who had initiated the subcontracting project in early 2019—with a book filled with nearly 150 photographs of Local 34 members. In every photograph, a worker held a sign calling on Yale to “Respect Our Work!”, with each sign including a personalized note explaining why they opposed subcontracting. “Good paying jobs with real benefits should stay in New Haven, which improves the local economy and lifts people out of poverty,” read one sign. “Everyone should have union representation. Worker rights are human rights,” read another.

In response to Local 34’s photo petition, Yale University Librarian Barbara Rockenbach said that the library is “contractually obligated to the companies doing this work, and we continue to believe this is the most effective solution for a time-sensitive, short-term need.” Rockenbach added that the library remains “committed to maintaining and supporting robust clerical and technical employment at the library and to advancing and supporting, wherever we can, Yale’s commitments to the New Haven community.”

While it is unclear how the library and university administration will ultimately respond to the petition’s demand for the library to commit to ending subcontracting, what is certainly clear is that, as in 1984, the library workers’ struggle is intimately related to deeper contestation over what the university is, and what it should become.

“Especially for people in the administration that I speak to, their first thought is that people like me and people who are activists hate the university, that we’re anti-university,” Baldwin told me. “Nothing could be further from the truth. The point is that if we take the charters of universities, their mission statements, the lofty claims of their capital campaigns, and the general presumption that universities’ job is to solve the most difficult problems that face the globe to their logical conclusion, why wouldn’t universities solve the problems in their own backyard, especially if they’re involved in creating those problems?”

Prostano offered a similar sentiment, reminding me that, engraved on the façade of Sterling Memorial Library is the phrase, “The Library is the heart of the University.” She and her colleagues want Yale to live up to that vaunted claim. They care about the university, just as they care about the city it calls home. For the Local 34 members pushing for more local hiring and an end to subcontracting, the goal isn’t to snuff out Yale’s heartbeat, but rather to make it thump to a tune that can appeal to everyone who lives and works under Yale’s ever-lengthening shadow.

Jack McCordick is a senior in Branford College.