Abigail Fields is excited. She’s not the only one.

The fifth-year PhD student in Yale’s French Department stands on the bed of a truck overlooking hundreds of protestors. It’s a chilly April evening. A sea of bright orange opens up below her, all shirts emblazoned with the words “Local 33 UNITE HERE,” the name of the union that Yale graduate student workers like Fields have been fighting to form. The crowd is with her, erupting into chants, cheers, and occasionally a smattering of boos aimed at Peter Salovey or the Yale administration.

Using a music stand as a makeshift podium, Fields begins speaking: “Without my labor and that of my colleagues in language departments, Yale’s language programs would not function.”

Her words, soon drowned out by the uproar, kick off the Union Yes Majority rally. It’s a demonstration celebrating the fact that more than 1,600 graduate student workers—a majority of the population of the School of Arts and Sciences—indicated they want a union at Yale. This level of support hasn’t been seen since early in the group’s thirty-year history, which has been obstructed by University union busting efforts.

“For too long, grad workers have been told that we should just feel lucky to be here at Yale,” genetics graduate student worker Arita Acharya GSD ’24 announces to the crowd, which has turned to face President Salovey’s red-bricked house on Hillhouse head-on. She adjusts her thin black glasses. “But the Yale name alone can’t pay my rent. It can’t heal me when I’m sick. And it can’t protect me from abuses of power.”

A grievance procedure. Better mental healthcare. Cost-of-living adjustment. A more democratic university. Across Salovey’s lawn, organizers stack huge cubes plastered with demands written by hundreds of graduate student workers.

“I want a union because if I’m going to be out here having kids, I can’t accept being treated like a kid myself,” graduate student worker Camila Marcone GSD ’27 chimes in from the truck bed. She stands tall, wearing a boldly accessorized version of the crowd’s orange uniform—with a black leather jacket, red lipstick, and cat eye sunglasses. She tells the crowd about the cost of missing healthcare benefits, a livable wage, and a contract. “And that is how Yale treats us! Not even a degree from Yale can promise a good stable job.”

Chants soar between speeches. Local 33 co-president Paul Seltzer GSD ’23 leads the crowd, calling out “When we fight!” to a resounding, “We win!” The chant—carried by Seltzer’s booming voice in spite of the wind—is a staple of labor demonstrations around Yale and New Haven, spanning many “we”s and linking the efforts of successive generations together.

Even more groundbreaking than the majority support at Yale is the long-building tsunami of unionization flooding the country, including that of graduate student workers at peer institutions like Brown, Harvard, MIT, and Columbia, who have all recently won recognition and contracts. Here in New Haven, labor activists are abuzz and mobilizing for change. This April rally includes graduate student speakers across departments, and representatives from Locals 34 and 35, the New Haven Board of Alders, MIT’s recently formed Graduate Student Union, Yale undergraduate-run Students Unite Now (SUN), the Graduate Hotel, and the local nonprofit New Haven Rising. Three months after their own Jackie Sims came to speak at the Local 33 rally, announcing the start of a union campaign, workers at the Graduate Hotel held elections and officially won their union.

“Yale better learn how to surf,” quips Bob Proto, President of Unite Here Local 35, which represents Yale’s service and maintenance workers. “Because there’s a wave coming on this campus, it’s long overdue… Without you, Yale doesn’t work.”

The public emergence of labor activism—bolstered by a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) and a presidential administration that are more sympathetic to workers’ rights than their predecessors—has helped infuse this generation of Local 33 organizers with fresh enthusiasm. Organizers with Local 33 have helped campaign with New Haven Rising—a local activist group fighting for economic, social, and racial justice in New Haven—for Yale Respect New Haven, and this summer they canvassed to improve local hiring practices. In Connecticut, Local 33 has no shortage of governmental support. Like Hurt, many representatives from the New Haven Board of Alders, including its President Tyishia Walker-Myers, attended and spoke at the rally. At the end of August, Connecticut Attorney General William Tong officially endorsed Local 33 and urged Yale to “commit to respecting [Local 33’s] rights to organize and unionize without interference or employer opposition,” marking one of the most significant endorsements in the group’s history.

These connections are also part of what makes Local 33 so unique. Its affiliation with UNITE HERE ties it to a broader network of hotel, food service, manufacturing, and laundry workers across the country—a connection unlike those of the independent union efforts at other universities. And the support it has found in New Haven reflects the broader pro-labor sentiments of a city that champions workers’ rights and autonomy, as well as harbors frustrations with Yale as an employer.

“When I come waltzing into your office and say, ‘hey, join the union,’ what I’m asking you to do is to think of yourself as having more in common with the person who cleans your office than with your advisor,” said Gabe Winant GRD ’18, a former Local 33 organizer and current Assistant Professor of History at the University of Chicago. He spoke passionately and eagerly with me on the phone, the sounds of cars rushing through the background. “That’s one of the most amazing things about the organization: it actually asks you to think about what place you want to have in [New Haven], in this community, and the kind of complex and unequal social relationships that make it up.”

Yale is no stranger to unions. The University already hosts five, two of which are affiliated with UNITE HERE—the group behind the latest graduate student effort at Yale. However, the University has never acknowledged Local 33—doing so would mean acknowledging Yale’s graduate student workers as actual workers, who work in labs, teach classes, and write grants. It’s a step that the administration has historically been unwilling to take.

“I want to welcome you to the most unionized university in the country!” Proto announces to the crowd of protesters, gesturing to the splendor of Schwarzman and Sheffield-Sterling-Strathcona Hall behind him. “What’s wrong with this picture? How come the custodians that clean the classrooms have the terms of their working conditions in writing, and the graduate teachers that teach in those same classrooms are ignored by the university?”

A history of denial

Yale has long rejected the notion that graduate student workers can be anything more than students. “University leaders firmly believe that graduate students are… here to learn to be scholars and teachers,” Dean of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Lynn Cooley wrote in an email to me in July, using words to the same effect of all the University’s public-facing comments on graduate student workers’ status for the past decade. “[T]heir curriculum includes opportunities to learn through instructing others.”

Graduate students, who are often required to work well over forty hours per week in order to teach classes and perform research, earn a stipend of $38,300 at Yale. There is little to no time for a second job, leaving these students overworked and underpaid—which Yale justifies by asserting that they are students, first and foremost, and students aren’t full-time employees. To emphasize the labor they perform on campus, members of Local 33 refer to themselves as “graduate student workers,” or even just “graduate workers” and “graduate researchers.”

At the end of August, Connecticut Attorney General William Tong officially endorsed Local 33 and urged Yale to “commit to respecting [Local 33’s] rights to organize and unionize without interference or employer opposition,” marking one of the most significant endorsements in the group’s history.

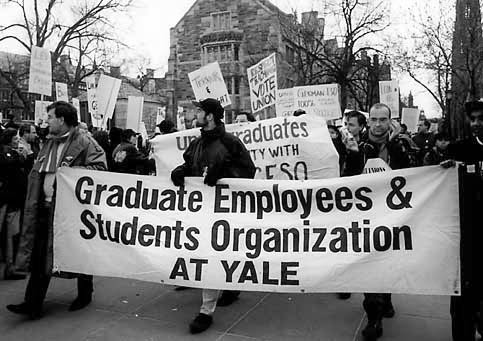

Graduate worker organizing at Yale has a rich history of action and pushback, as outlined in the Minnesota Review’s “On Strike at Yale,” written by GESO organizer Cynthia Young GRD ’99. In 1971, teaching assistants in the Philosophy department withheld fall semester grades to protest their wages—$400 per semester—and prompted the administration to double TA wages. In 1986, seven teaching assistants formed the “TA Solidarity Group” to protest the poor working conditions at the University, which denied student workers health care or livable wages, with some workers not paid at all. Advised by a member of Local 34 who sat in on meetings, the group slowly grew and changed its name to the Graduate Employees and Students Organization (GESO) in 1990, when it began seeking official union status. GESO organized a majority of graduate student workers—1,400 out of 2,200—in a series of strikes in the 1991-1992 and 1995-1996 academic years. The University came down hard on organizers, threatening expulsion and holding disciplinary hearings that resulted in one teaching assistant losing her spring semester teaching job. Without federal worker status and protection, graduate student workers were left relatively defenseless against the University’s will despite widespread student support.

Insufficient labor laws and the precarity of relying on federal decision-making has placed graduate student employees in a delicate position for much of their history. From the nineteen-thirties to the nineteen-seventies, Congress frequently updated legislation to clarify the definition of workers. This trend ended with the 1974 amendment of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) to protect hospital and nursing home healthcare workers as worker rights were becoming increasingly politicized. The original NLRA law, passed in 1935, provided private-sector workers the rights to organize, seek better working conditions, and represent themselves without fear of retaliation. After the 1974 amendment, matters of worker status, the rights to organize, and collective bargaining fell into the hands of the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB)—a federal agency governed by five President-appointed board members, which primarily acts as a judicial body to decide private sector cases. These cases allow the Board to establish or curtail worker rights, the most controversial of which could then be reversed by subsequent board members.

In 2000, the Clinton-led NLRB ruled to grant worker status, and thus protection of the NLRA, to graduate student workers at private universities. Because the NLRA protections do not apply to government employees, graduate student workers at public universities are exempt altogether, leaving individual states with the ability to determine workers’ right to organize. But even graduate student workers at private universities soon lost their protections, as the decision was overturned and reversed by the Bush-appointed board in 2004.

In August of 2016, the Obama-appointed NLRB re-affirmed that student employees at private universities held the right to unionize. On the day of the decision, President Salovey sent a letter to the Yale community expressing his disagreement: unionizing, he said, would tarnish teacher-student relationships with a “formal collective bargaining regime.” Yale has continued to deny its student workers employee status.

“Their opposition to the union was economic. They didn’t want to pay us more money, I’m sure,” Winant said. “But more than that, it was ideological. And that was why they fought so hard.”

Winant helped spearhead the last major push for a union during his final years at Yale, in 2016 and 2017. After the 2016 NLRB ruling, Local 33 quickly filed with the NLRB for a vote of legitimacy, pursuing departmental voting (a “micro-unit” strategy) as opposed to a simple majority. This strategy meant only a handful of departments—all of which had strong Local 33 support—would proceed with official elections, with the hope of winning a union that would represent each individual department rather than the entire graduate student body. The decision was controversial, and the University publicly accused Local 33 of voter suppression as well as aggressive recruiting tactics.

Insufficient labor laws and the precarity of relying on federal decision-making has placed graduate student employees in a delicate position for much of their history.

“When you organize workers or a group of people, the goal is to build power… you want to build enough power to protect the membership, to protect the workers,” Viet Trinh GRD ’18, a former Local 33 organizer, said after pausing for a moment. “In order to build power, you need to win.”

That power was tested when the University took Local 33—then GESO—to court in the fall of 2016. Yale asserted that graduate students were not workers—an ideological position in direct violation of the NLRB ruling — and that departmental elections should not be allowed. The University hired Proskauer Rose LLP, a New York City-based law firm notorious for union-busting that has fought against workers at Volkswagen, players in the NFL, NBA and NHL, and, most recently, technology and product staffers at The New York Times.

What should have been a routine hearing, culminating in the dismissal of Yale’s case, ended up lasting around two months. Winant attributed this delay largely to the University slowing down proceedings by deliberately submitting paperwork incorrectly or requesting additional hearings on trivial matters, a tactic “universal to union busting” to demoralize and frustrate union organizers.

Ultimately, the judge ruled in favor of Local 33. The group held elections in nine of the Graduate School departments in February of 2017, winning in eight of them. Yale appealed the hearing’s results, forcing a second legal battle. Between the initial hearings and the election, Trump was elected president, forcing Local 33 organizers to prepare for an anti-labor administration that could reverse the 2016 NLRB decision granting graduate student workers the right to unionize.

In hopes of forcing Yale to negotiate, and calling attention to the University’s strategic stalling of deliberations so that they would carry over into Trump’s term, Local 33 members turned to demonstration. They held rallies during a weeks-long hunger strike, with several demonstrators requiring wheelchairs due to complete exhaustion, and occupied Beinecke Plaza with an encampment—dubbed 33 Wall Street—sporting picnic tables, electrical lighting, and bookcases full of board games, history textbooks, and political nonfiction.

Ultimately, the fight for formal recognition was unsuccessful. In the summer of 2017, Yale’s Local 33 organizers made the painful decision to withdraw their petitions from the NLRB, alongside other graduate student workers at Boston College and the University of Chicago. The organizers feared a hostile Trump-appointed NLRB could use any one of their cases as an excuse to overturn the 2016 decision and revoke graduate student workers’ right to unionize across the country. They hoped for their right to organize to continue existing, to get through the next four years, and to eventually restart the formal recognition process, post-Trump.

Finding agency

“I think one of the things that’s pretty remarkable is just how constant some of the things are,” Ridge Liu, Co-President of Local 33 and fifth-year PhD student in the physics department, told me. Liu explained that, throughout his entire time at Yale, people have talked about the same issues—lack of a third party grievance procedure, good mental healthcare, support for international students. Without a union, he believes these problems will continue to haunt future generations of graduate workers.

Liu began his time at Yale in 2018, during the Trump administration, on the heels of Local 33’s defeat in gaining union status. He recalls the end of his first year culminating in “A Failure to Commit,” a report holding the University accountable for its failure to deliver on promises of hiring more New Haven residents, as well as recruiting more faculty of color. The report underscored that without formal accountability methods—like a unionized staff—Yale would continue to violate its espoused values of diversity, equity, and inclusion behind closed doors.

Today, organizers with Local 33, Locals 34 and 35, and other New Haven organizations like New Haven Rising have continued to press Yale to expand their local hiring practices and contributions to New Haven. Many hope Local 33 could push Yale to increase its financial support of New Haven, provide a higher baseline support for all of its workers, and truly commit to diversity in hiring goals.

“A union would also give us the power to hold Yale accountable and make this a university that doesn’t just talk about lofty goals of bettering the world but makes real, material commitments to the New Haven community that supports and surrounds it,” Micah English GSD ’26, a PhD student in the Political Science Department, said at the rally, peering out at the crowd in front of her from beneath her brown knitted bucket hat. She highlighted research demonstrating that unions help foster racial solidarity and increase feelings of belonging. “As members of the Yale community, we should do all we can to ensure Yale is living up to its stated value of justice and fair opportunities for all.”

A union, English said, could help formally enact protections for graduate student workers by establishing a grievance procedure. Currently, issues that arise in the workplace have to be taken up with supervisors—including grievances caused by their own supervisors. An independent third party could receive those complaints and handle them without bias. Local 33 members tout neutral third party arbitration, along with increased inclusion and diversity, as possibilities enabled by a union contract.

“Autonomy in the workplace is one good, important issue, but broader welfare practices and safety nets are important for any sort of worker, including graduate students who are teaching and doing research,” Mustafa Yavas GRD ’20, a Local 33 alum and postdoctoral associate in the NYU Abu Dhabi sociology department, told me in a voice memo in April.

These demands are not abstractions for the Local 33 organizers, but everyday realities born from lived experience. Liu came to Yale to study theoretical particle physics, a branch of physics that examines the components of the universe in their most basic forms. But at the beginning of the pandemic, funding uncertainties and the difficulty of working online forced Liu out of his research group. He now studies subatomic particles called neutrinos with an experimental particle physics group, expressing that even though he enjoys this group, he’s frustrated that Yale pulled back on his original group’s funding in a year where their endowment grew by billions of dollars.

“We need a contract. We don’t have a document that lays out: here’s the conditions of our work; here’s what you get for doing this work. If things go wrong, here is a process that you can trust that will…get a resolution for you,” Liu explains. “None of those things are codified in a way that is binding and that we as graduate workers really have a way to be at the table.”

Liu’s co-president, Seltzer, who works in the history department, shared his experience with lack of agency at the April rally: “We’ve taught in crowded, poorly ventilated rooms with no guarantee of high quality masks and no consistent policies for what happens if we or our students get Covid. I need a union because I need a say in the basic conditions of the work that I do.”

An unhealthy relationship

The pandemic forced another of Yale’s shortcomings into the spotlight: healthcare. From big picture issues like mental health coverage, expensive dental and visual premiums, to the day-to-day safety conditions of the labs they work in, graduate student workers are finding themselves left unattended by the institution they work for.

Expensive healthcare premiums exist on top of substantial out-of-pocket costs. Buğra Şahin, an international student and third year in the Chemical and Environmental Engineering department, recounted paying $3,000—about 8 percent of his yearly salary—out of pocket for a medically necessary dental procedure last year, leaving him living paycheck to paycheck.

When he spoke at the rally, Şahin’s voice was full of passion, reaching a firm, forceful crescendo at his conclusion: “To be able to flourish and excel in our work that we do for Yale, mind you, we have to have our basic healthcare needs met,” Şahin said.

Local 33 alum Yavas remembered the lack of dental and vision coverage from his time at Yale, adding, “It’s obscene that dental care and eye care is still not included in the graduate student healthcare package, as if our eyes and our teeth are not part of our bodies or health.” No changes to the current healthcare plan have been reported as of the start of the 2022 academic year.

Graduate worker unions at Harvard and Columbia have pushed their schools to cover 75 percent of dental premiums, with Columbia even establishing a support fund with more than two million dollars available to cover out-of-pocket medical, dental, and vision costs. Here in New Haven, Locals 34 and 35 have negotiated with Yale to cover 100 percent of routine dental work and 80 percent of emergency operations.

Other alumni also spoke about negative experiences with accessing healthcare at Yale. Trinh found himself unable to get a medicine he’d been taking for six years twice throughout his first three years at Yale. After several attempts to make an appointment, Trinh gave up trying. “I think I was one of those folks who kind of fell through the cracks of Yale Health.”

If there are cracks in Yale’s general health system, then its Mental Health & Counseling department has chasms. Alumni and current graduate student workers alike recounted experiences with long wait times, short treatment windows, and poorly matched therapists.

“It’s an incredibly opaque system that requires an absurd amount of work on the part of people who need help,” Trinh said. “It seems set up to aggravate the very kind of conditions that healthcare is supposed to treat…. I think we see the failures of that system reflected in—if I can be frank—the poor mental health outcomes of Yale students, both graduate and undergraduate.”

Others, like Winant, voiced their experiences of feeling misunderstood by healthcare professionals who had mainly been trained to deal with 18- and 19-year-old college students. “I felt like we were just getting processed and pushed through,” Winant said.

In a mental health system known for relegating all it serves to long wait times and dissatisfactory treatment services, graduate student workers bear the brunt of the obstacles. Some progress may happen soon—Dean Cooley wrote to me that, in response to a push by the Graduate School Assembly, she anticipates a “GSAS-specific embedded mental health counselor” will be in place by Fall 2022—but, for many graduate student workers whose mental health needs have been long ignored, this comes too little, too late.

Paying the price

In addition to pointing out the need for safer working environments, Local 33’s requests for contracts and better healthcare reveal the deeper economic precarity facing many graduate student workers. This starts, quite simply, with the salary Yale pays its student workers.

“The salary that Yale pays its graduate students is no longer competitive in the way that it would’ve been, for instance, a decade ago,” Trinh told me over Zoom in April. The impact of this discrepancy, he noted, is much bigger than graduate students—it hurts the University, graduate student workers, and undergraduates alike when they “have to be taught by people who are worried about where their next paycheck is going to come from.”

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimated the average wage for a “postsecondary teaching assistant”—the best fit category for a graduate student worker—was $41,170 in May 2021. Stipends in Yale’s Graduate School were recently raised and now range from $38,300 to $40,000—well below the national average, despite coming from one of the wealthiest universities in the world. While students can request additional family subsidies if they plan on expanding their families, or medical leave funds and conference fellowship funds, all of these require extra criteria and are not a baseline need met by the university. Graduate worker pay at peer unionized universities like Columbia, Harvard, and Brown is significantly higher—with minimum PhD pay at Brown resting at $42,411 per year, 10 percent more than Yale’s $38,300 despite Brown’s endowment being $35.4 billion less.

“I think the big dirty secret of academia is that graduate student instructors—including at Yale—do a significant plurality of the teaching, if not the majority of the teaching,” Trinh said. “And the truth is that part of the way that these universities balance their books and make a profit is by underpaying us. That’s part of the calculus they make.”

This calculus is being felt, hard, by graduate student workers, particularly amid the current period of inflation and rising rent prices.

“Rent has gone up,” Liu said over the summer. “People are really feeling the stakes of what’s going on and of our lack of power in the university.”

The New Haven Register reported that rent has climbed by about 25 percent in New Haven in the past year. The average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in New Haven is $1,895 per month. Annually, this would cost graduate student workers around $22,000—about 60 percent of their salaries from Yale. Average rent is 32 percent of the typical Americans’ pay, according to Business Insider, and financial experts recommend keeping monthly housing costs at less than 30 percent of income. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Expenditure Data from 2020, adding up the spending of an average American on only a few necessities—rent, transportation, and food—totals to $39,142, more than a thousand more than a base graduate worker salary.

Anti-union pundits often portray graduate student workers as ungrateful ivory tower elites, but many students are pushing back against this narrative.

“I come from a working class family,” Madison Rackear, a fourth-year PhD student in the genetics department, told me over the summer. “I was the first in my family to go to college. I do have student debt…. moving to New Haven was a really big jump for me. I came straight from undergrad, and it required a lot of money and time and resources that were, I think, very stressful to me at that time. And I kind of came into New Haven feeling already as if Yale was not doing its due diligence to support graduate workers that it was recruiting to the area.”

Rackear went on to explain how they first worked in a lab at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill in order to make money to stay on campus over the summer. After that, Rackear applied to graduate school knowing that a PhD in genetics would secure them more financial security, even if they weren’t planning on staying in academia.

“It really just allows certain doors to be open that are otherwise not in this field,” Rackear said. “So I went under the guise of some sort of financial security, and then unfortunately I think I quickly realized that that comes at the cost of a shorter period of financial instability for a lot of graduate workers, myself included.”

Local 33 alumnus Winant describes his own version of this “bargain”—trading long-term financial security for short-term financial insecurity—which broke down when he arrived on campus in the fall of 2010.

“The academic job market was in really bad shape,” Winant said, adding that the “rough, impoverished seven years” of PhD work no longer translated to getting a high-paying job. “So it seemed to me like more power for people at the bottom end of the system seemed important if we’re gonna figure out how to renegotiate that bargain in some kind of way.”

The decline of stable, well-paying job opportunities for PhD students is not merely a historical phenomenon; it is very much a challenge of today. In 1995, roughly half of those teaching at colleges were tenured or on track to get it, as reported by The New York Times. Twenty-five years later, in 2020, a study by the American Association of University Professors found that only 31 percent of American college faculty members were tenured or eligible for tenure. These numbers indicate the rise of contingent faculty—a class of faculty with lower pay, less job security, and less academic clout—who allow universities to balance their books and maintain large enrollment numbers. Since the majority of academic workers will end up in these precarious jobs, more graduate student workers than ever before are fighting for a smaller pool of stable, tenure-track spots.

In 2014, after months of protests, open letters, and articles by Local 33 organizers, the University rolled out an automatic, six-year funding plan in the humanities and social sciences. But Winant noted that the University framed it as an independently-driven, internal decision.

“They don’t want to convey to people that they’re participating in a kind of negotiating process,” Winant explained. “They want to have monopolized decision making.”

According to Winant, the role of graduate student workers was to generate pressure through petitions, open letters, demonstrations, and faculty conversations, which would then be passed up to the administration. The University would never negotiate openly with Local 33 because doing so would confer recognition, allowing graduate workers collective bargaining power, increased autonomy, and the potential for even bigger change—supported by legal protections.

Yale’s existential crisis

Yale is part corporation, part school. Navigating graduate student workers’ search for worker recognition exacerbates its identity crisis. The question of Local 33’s status brings Yale’s dualism to an unsettling head—forcing the University to admit that even its own students feel the tension between Yale as educator and employer. If graduate student workers unionize, the University might become overtly corporate, forfeiting its carefully crafted educational landscape.

“I think universities, writ large, need to have a serious, serious reckoning with what their priorities are. Because tuitions are going up and that’s bad for the students. But that money isn’t going to the people doing the actual teaching. It’s just not. So where is the money going? And if it’s not going to the people doing the teaching, then what’s the mission of the university?” Trinh explained, talking faster and faster as he went. “And we’re starting to realize that these universities, even though they do do a lot of teaching and that is one of their missions, it doesn’t seem to be the primary mission anymore.”

Others have been even more explicit in likening Yale to major companies.

“I think in some ways [Yale] act[s] just like any other corporation,” Winant tells me. “No corporation wants its workers unionized, anywhere, basically, ever. And we’re seeing that now, like at Starbucks, for example.”

“I’ll be the first to admit that we are fortunate to be able to teach. But, that doesn’t negate the

fact that what we are doing is labor.”

Winant detailed for me the union busting techniques used during his time at Yale—from the anti-union lawyers in the NLRB hearings, to the attitudes of many professors. He emphasized how subtle these acts of deterrence could be, recounting how a faculty advisor had once stared and then scoffed at a colleague’s union button, which discouraged them from wearing it to their lab again. Since many graduate student workers rely on their professors and advisors for securing careers outside of Yale, even the slightest tension can feel disastrous. Ultimately, he noted that Yale’s aggressive legal pushback to union efforts established a firm precedent on how hard they would fight a union.

“I think at some level the whole industry, or at least important pockets of the industry, are just really ideologically dug in,” Winant said.

Another dual identity

Yale isn’t the only one who struggles to identify graduate student workers as workers—the student workers themselves sometimes find it difficult to characterize their own identities. Many enter graduate school conceiving of themselves as students alone, passionate about their academic interests and seeking a role in expanding their areas of research. When they get here and realize the reality of their status, they have to broaden their self-understanding as workers, too.

“When [graduate students are] thinking about unionizing, they’re making a decision about how to define themselves. Because they’re both employees and these kind of apprentice professionals at the same time,” Winant said.

Organizers at the rally were conscious of this dynamic. The narrative of who a graduate student worker is and what they do has been re-imagined—in large part thanks to decades of organizing—and is reaching fruition right now, at Yale and across the country.

“Some of you may be uncomfortable with the phrase ‘student worker,’” English began during her speech at the rally. “I’ll be the first to admit that we are fortunate to be able to teach. But, that doesn’t negate the fact that what we are doing is labor.”

Countless graduate student workers spoke about their experience working in labs, teaching in classrooms, and writing grants.

“And we’re starting to realize that these universities, even

though they do do a lot of teaching and that is one of their

missions, it doesn’t seem to be the primary mission anymore.”

Out of this new working identity comes a unique, built-in community. Many alumni and current graduate student workers point to this community as their favorite part of Local 33. “The part of the job that I enjoyed the most actually was just, it became kind of an excuse to regularly check in with my peers and to kind of shoot the shit with them,” Trinh said with the hint of a smile. “It became a way for me to discuss what was going on in their lives and what resources they needed.”

Now, that community is more vibrant than ever.

“I think the conversations have been easy. They have felt as if people are able to share their stories to folks who they have not ever had a chance to connect with,” Rackear said. “Yale does not necessarily do a lot to make grad workers feel as if they’re in community with both Yale and New Haven, and I think that that is something that Local 33 is providing. I think that that combined with people’s desire for things to be different here has been really motivating.”

Perhaps this fresh wave of organizing can be best explained by the word that kept cropping up in my conversations with members of Local 33: excitement. When we talked on the phone over the summer, Liu said with a laugh, “We’re going to win.”

“It’s that excitement and that energy. That’s where that comes from, from the organizing, from the work of talking to everyone,” Liu said, his words spilling out quickly as he shared just how special the current feeling is. “But when we’re going on visits and talking to scientists and labs and going to talk with humanists in libraries and stuff, I see it there all the time. And that’s something that is really moving… an experience of real solidarity.”

The mountain ahead

The process of change is frustrating—especially when Yale often refuses to allow organizers agency or credit for the changes that their hard work has actualized. Despite it all, many of the organizers express optimism.

“I have a lot of hope that the University can this time choose to do the right thing and acknowledge that we are workers and that we have the right to unionize and that we have the right to do that unimpeded,” Liu said, pausing to choose his words carefully. “I hope that they can choose not to run an anti-union campaign, is what I guess I’m saying. Because we’ve seen examples of employers do this, even in New Haven, at the Graduate Hotel downtown.”

The Graduate Hotel chose to voluntarily recognize and negotiate with its union instead of fighting through the legal system. UNITE HERE organizers and allies gathered in July to celebrate the win, praising the Graduate for not union busting and elevating them as a model for local employers.

“Graduate Hotel workers changed their workplace for the better, and we can do the same thing right here at Yale,” Seltzer said, as quoted by the New Haven Independent. “The Graduate Hotel did things right by recognizing the union and settling a fair contract quickly. It’s a shame that other employers don’t follow their lead.”

Seltzer’s call on Yale pointedly invokes decades of union hostility between graduate student workers and the University. And with this fresh example of an employer remaining neutral and quickly settling a contract, Yale’s obstinance becomes even more pronounced.

“Yale has a lot of organized power,” Trinh told me. “The goal of the union is to out-organize the university. And that is a very difficult task to do when the university has [forty] something billion dollars, and the graduate students are making, what, thirty thousand dollars a year. We are fighting a Goliath with more resources and more power and an absurd amount of money that none of us can really fathom.”

Trinh asserts that the lack of graduate student worker success is not for lack of trying, competency, or strategy. It’s the direct result of Yale’s deep-set resistance—fortified by its deep pockets—to worker power. Organizing at Yale requires vast amounts of patience, effort, and generational knowledge—all things that are incredibly difficult to build across workers who only have a six-to-eight year term at the University.

“That’s the hill that we’re climbing,” Trinh said. “And we’re working on it. But we are climbing a very, very, very steep mountain.”

Continuing its decades-long journey to build power, Local 33 has begun its newest venture: signing union cards, which could lead to another formal NLRB vote or—in an unprecedented reversal—voluntary University acknowledgement. On the first day of September, Fields stands outside the Humanities Quadrangle, wearing an orange Local 33 shirt tucked into blue jeans. In front of her rests a small plastic table—one of many across campus—filled with pens and paper and plastered with “Union Yes!” posters. She can’t help but smile as she tells me how she and her colleagues will be there the rest of the day, and the day after. However long it takes.

— Abbey Kim is a sophomore in Branford College and an Associate Editor of The New Journal.