The first thing I noticed was the smell. Cedar pitch, freshly sawn pine, and a trace of coffee from the manager Mark’s travel mug, steaming on a countertop. The characteristic smells of a woodshop – to be precise, the Berkeley woodshop. That fall in 2019, I spent many Saturday mornings working on a small table, trimming and planing elm boards for the surface, cutting mahogany legs with a jigsaw and sanding them smooth. It took months to finish, and I was proud of it. For a while the table lived in my suite, but eventually I moved it to the Silliman art room, giving the still-sharp smell of finish time to air out.

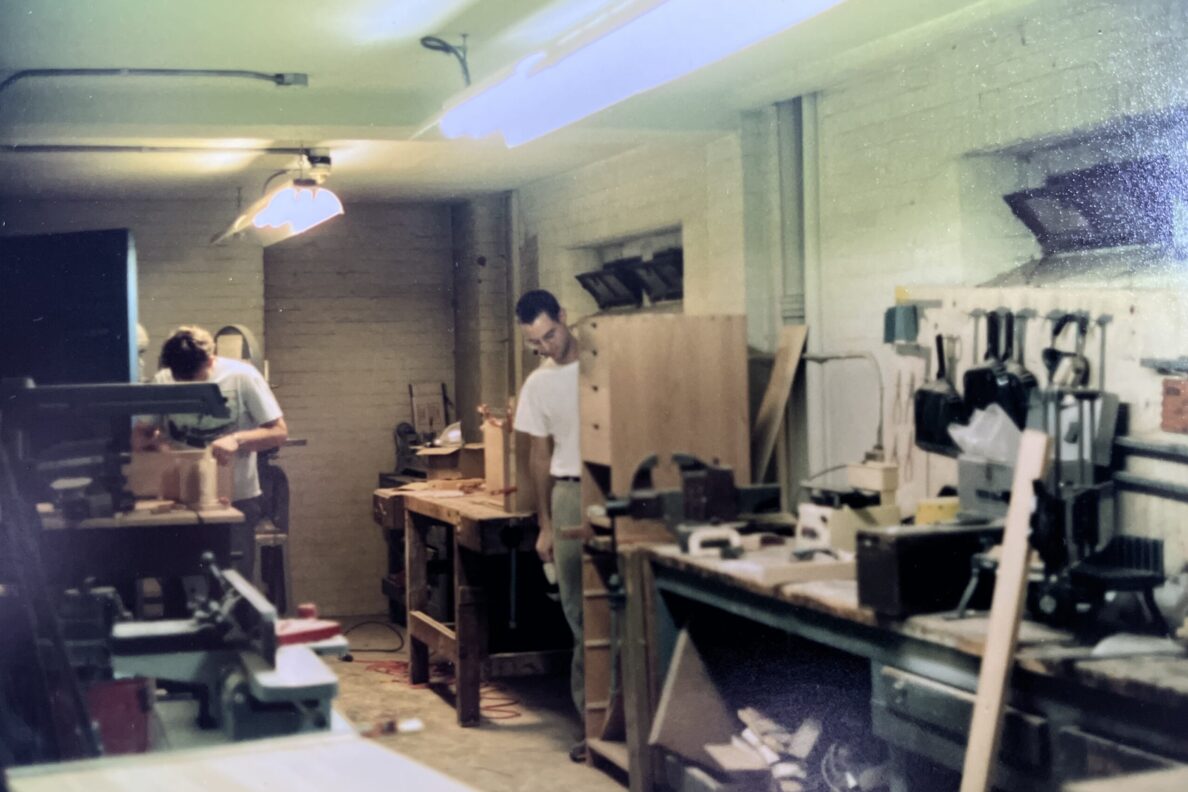

For thirty years the woodshop was open to anyone who would wake up at 9 a.m. on a Saturday—and many did. It was a small space, but efficiently laid out. The large table saw, the dark green joiner, the lathe corner and the stacks of various boards and plywood—somehow none of it really got in your way. One woodshop alum, Kate, told me that the woodshop was one of her favorite places on campus. Another said he “treasured the time spent in community with other students who were making things.” For almost everyone I spoke with, the workshop was their escape from academic pressure. Over the years and with Mark’s tutelage, this hidden community created blanket chests, sparring dummies, conductors’ batons, coffee tables with inlaid chess boards, salad bowls, hand-turned pens,—all of a quality one would have trouble attributing to the untrained hands of undergraduates.

“The place used to be humming,” Mark told me, “people coming in, having fun, ideas on the table.” Today, the room that once housed the woodshop sits nearly empty, with only a couple computers and a couch. Maybe if you’re lucky you can spot a bit of sawdust still nestled beneath the baseboards.

One evening last summer, while working in Berlin, I gave Mark a call. Ever since the start of the pandemic, we’ve chatted and caught up every now and then. We spoke for a few hours—with one brief interruption as Mark greeted a prospective blueberry picker and directed them to the patch behind his house—and we discussed his retirement, the projects he’s still working on despite retirement, Berlin, and finally, the woodshop.

“Do you think it’ll ever make a comeback?”

“No,” he said, flippant. “I’ll put it this way. How many darkrooms are left on campus?”

The answer is not many, and access to those remaining is limited. Woodworking has gone the same direction. While there are workshops for wood sculpture and some facilities in the Center for Engineering Innovation and Design (CEID), these are spaces restricted to students in the relevant classes, offer little to no guidance, or require an obstructive amount of training. And anyway, cutting plywood sheets on a CNC machine feels different than watching wood curl away underneath a sharp plane.

When I ask directly why Mark thinks the woodshop closed, his voice is solemn but his answer’s tongue-in-cheek: “It was Youtube.” Students can put on a woodworking video and get the satisfaction of watching someone make something without the trouble of actually doing it themselves. Maybe so.

But it’d be impossible to pin down exactly why the woodshop closed; there are so many plausible reasons. Saws are dangerous, students are busy, and instant gratification really is nice! By and large the digital age has set traditional woodworking on uncertain footing, not to mention that Saturday Morning Woodshop Hobbyist is hardly prime resumé material. And this story isn’t new: the woodshop’s popularity had been waning for years before covid—some Saturday mornings in 2019 it was just Mark, my friend and I. Teru, who was in the shop during the late 90s, was just amazed the Berkeley woodshop lasted as long as it did.

The story of the Berkeley woodshop now resembles many of the projects that began there. A half-turned wooden cup, a chess set missing everything but pawns, two table legs abandoned on a shelf. We set down our tools and things remain incomplete, leaving behind ghostly traces. Or specks of sawdust.

Yet it doesn’t all disappear: people got more from the shop than simply the satisfaction of making something with their hands. One woodshop alum, now a plastic surgeon, left Yale with both a rock maple trestle-style coffee table and one of Mark’s adages: If you don’t have time to do it right, you don’t have time to do it twice. Another told me that whenever he sees a ginkgo tree or tries to touch his toes, he thinks of Mark and the woodshop. He and his wife still use a mahogany salad bowl that Mark turned for them as a wedding gift nearly every day.

The woodshop was an imperfect space. It was loud, the students often inefficient, and when Mark describes himself he often favors “grumpy old man.” But something special wove all of this together, something that now lives in the past. This isn’t meant in a let’s-try-to-revive-it way. Some things can’t be brought back and that’s okay. Instead, I’m remembering a phrase my ceramics teacher said sometimes when she sold or accidentally broke her pottery: hold on tightly, let go lightly.

I imagine Mark driving south down I-91, as the 8 a.m. sun peeks through autumn foliage, or wintry snow-laden branches, or the fresh leaves in spring; this, nearly every Saturday of every semester for 30 years. I imagine a student finally turning a bowl that doesn’t crack, someone laughing from the adrenaline of cutting a board on the table-saw, a student taking the first seat on a lacquered chair they’ve been working on all semester. I imagine Mark smiling with them.

On the phone, Mark told me that on every job—whether building a kitchen or restoring a dresser—you always end up bleeding a little. For most of his career he’d wipe this inevitable bit of blood off. These days, he leaves it on, sealing it over with a layer of Shellac. “It’s like saying I was there.”

When I returned to campus in 2021, the table I’d made in the woodshop was gone. Maybe it’s my fault for leaving it in the Silliman art room, but in any case, it’s gone, and it’s alright. Sometimes I show people pictures, saying maybe one day it’ll show up. And sometimes, I call Mark and remember the woodshop.

— Austin Todd is a senior in Pierson College.