On March 31, self-taught artist and high-fashion lover Gordon Skinner hosted his 35th birthday party in the basement of Gilt Bar. Guests–including Shante Skinner, his half-sister and confidante, Bob Albert, his friend and agent, and Coco and Breezy Dotson, twin sisters and designers of a celebrity-approved accessories line who posed with Skinner’s art in Dekit Magazine–yelled into each other’s ears as a DJ played hip hop at jack hammer decibels. Skinner drank directly from a bottle of Moet & Chandon.

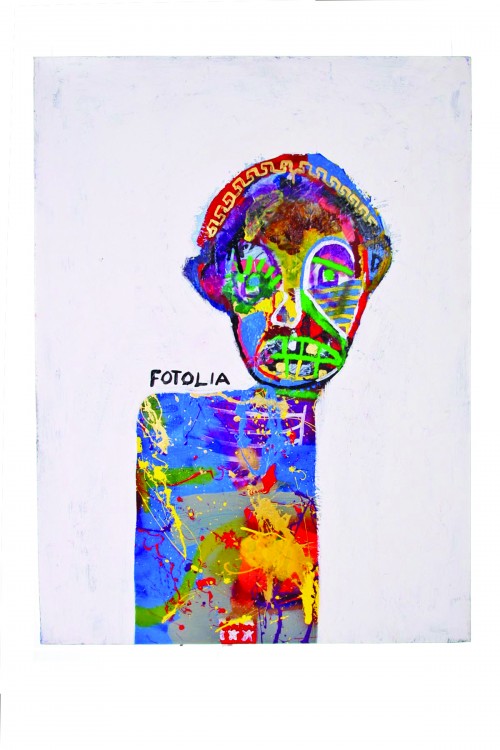

He had reason to celebrate: In January, only three years after he began painting, his first solo show opened at the New Haven Public Library. He was then profiled in the New Haven Independent and interviewed on local TV station WTNH. While the stories featured Skinner’s colorful, figural, and mask-like paintings, they also examined his background. Skinner grew up in New Haven’s South Church Street housing project. His absent father was a heroin addict who subsequently died from AIDS when Skinner was 15. When he was 10, his mother and stepfather moved to suburban Hamden, where Skinner felt isolated as one of the few black kids in school. His paintings are an attempt to give voice to the community in which he grew up, which, he says, is not often represented in popular contemporary art. “I want to be a voice for the people,” he said.

If the party also seemed like a prequel, it was because Skinner did not yet feel like he had been able to share that voice. He wanted more recognition from what he called the “elitist” and “pretentious” art world. He wanted to start selling his paintings so that he could quit his jobs and paint full time. He wanted, someday, to move from New Haven to New York, where there are more artists and arts-related events.

A week later, I sat with Skinner outside the Brooklyn Museum, talking about an exhibit we had just seen by famed visual artist Keith Haring. Skinner told me that he hoped to someday have his work displayed in a museum. Before that, though, he just wanted to be able to paint on his own terms. “I’ve worked for people all my life,” he said. “This is my time.”

When I met Skinner last spring, I knew nothing about the process of becoming a professional artist. The art world was more of a mystery to me than it was to him. Even after speaking to artists, collectors, gallery owners, and a Yale History of Art professor, I did not understand what qualities distinguished art shown in expensive Chelsea galleries from art that was never seen.

In the process of exploring these questions, I found two different spaces in New Haven that try to break down these barriers in the art world. Artspace, a New Haven nonprofit, gives artists strategies to get their work seen within a traditional gallery framework, as well as exhibition opportunities in both conventional and unconventional spaces. People’s Arts Collective, a newly founded organization trying to break down the art world’s economic and racial boundaries, aims not to operate within traditional frameworks at all. I realized that while access to more resources might make it easier for an artist to reach a broad audience, some artists choose to define their own success instead of allowing it to be dictated by a standard measure of popularity.

Artspace was founded in 1984 by a group of local artists seeking more opportunities to share their work with the public. It regularly hosts exhibitions in its gallery space on Orange Street and also helps artists get seen in other venues. This October, Artspace kicked off the fifteenth annual iteration of City-Wide Open Studios, which allows nearly three hundred artists in the area to share their work with the public–far more than could be featured in New Haven’s galleries in a year. The non-profit’s Executive Director Helen Kauder said CWOS “is a very democratic, inclusive event.”

Anyone who defined him or herself as a visual artist was invited to participate, just as anyone can become an Artspace member. Over the course of the first three weekends of this October, CWOS will be bringing visitors to artists’ private studios in New Haven, North Haven, and Hamden, to the group of studios in a former factory in Erector Square, and to site-specific art installations in the New Haven Register building.

Because there are only four commercial galleries, three co-op galleries and three non-profit galleries in New Haven and only a handful more in the surrounding region, according to Cynthia Clair, the Executive Director of the Arts Council of New Haven, getting art into them often proves difficult. Skinner spent two years driving to galleries in New Haven, Bridgeport, Westport, and Stamford, a painting or two sitting in his trunk, hoping to convince them to display his work. For years, he had little success.

On the last Sunday in September, twenty-three curators, gallery directors, and art scholars– the kind of professionals Skinner needs to impress to get his work seen–gathered at Artspace for “Speed/Networking/Live!” Artists had three minutes to explain their work to the professionals, who responded with two minutes of feedback. “There are many occasions when an artist might meet a collector, a curator, or someone who works at a museum, and the artist doesn’t have his or her work there, but has an opportunity to say something,” Kauder said. “The question is, how does an artist put his or her best foot forward?” The event was an opportunity for artists to try up to twenty-three ways of talking about their work in the most compelling way. Daniel Belasco, a New York-based freelance curator who participated in the networking event both this year and last year, said, “[Artists] could practice their pitch in the shower. What’s most important is to get feedback.”

As Kauder prepped the professionals inside, JP Culligan, an artist and an Artspace employee, stood outside and asked the arriving artists to wait on the street until the event’s one p.m. start time. Culligan grew up in New Haven and graduated from the Hartford Art School with a degree in printmaking. He told me that because a lot of art internships, jobs, and exhibitions require resumes and artist statements, he values the opportunity to meet these professionals face-to-face. “I tend to do better with these things when I actually get to talk to people,” he said. Bryant Davis brought printouts of his digital art, which he calls “homoceptual blending” and which involves breaking down JPEG files. He agreed with Culligan. “It’s nice to actually get to meet somebody and talk to them,” he said. Like Culligan, Davis formally studied art, graduating from The New School’s Parsons School of Design.

Skinner, on the other hand, did not go to art school or college, and he didn’t know that Artspace hosted networking events in addition to being a gallery space. On September 20th, when his second solo show, “Hard Works,” opened at the DaSilva Gallery in New Haven’s Westville neighborhood, the reception was primarily attended by his friends, family, and previous supporters. He is frustrated by the difficulties in getting the other people he wants to see his paintings– including those who run art foundations, contemporary art museums, and large commercial galleries–to attend a show at a small gallery in Westville.

“The biggest problem,” he said, “is the disconnect between myself and the movers and shakers in the art world.” His agent Albert agrees that getting art into galleries is difficult, “especially if you don’t have a resume already, if you haven’t shown at such and such galleries or graduated from such and such schools.” Albert, a cinematographer and self-described “marketing consultant,” met Skinner at the Fernando Luis Alvarez Gallery in Stamford while Albert was filming a reception. The two men became friends, and Albert subsequently made a short documentary about Skinner. Like Skinner, Albert is an outsider in the art world, despite having some experience in the film industry.

While Skinner may resent his separation from the more traditional art world, his position as an outsider also shapes his art. The poster for “Hard Works” was designed to mimic a timesheet, a reference to Skinner’s working class background and the eighty hours a week he works as an aide to developmentally disabled adults. Some of his paintings, like “Crack Baby” and “Jesus Piece” explicitly reference the poverty, drugs, and diseases he encountered during his childhood.

Sometimes Skinner worries that gallery owners “want to see me in a cardboard box, living under my paintings or some shit,” so that they can swoop in and save him, and that his art isn’t as appealing to them once they find out that his personal narrative isn’t quite that dramatic. Trying to gain their approval, and crafting a compelling story to draw them in, frustrates Skinner on principle, but he believes that it is necessary. Seeking validation “can go against everything you stand for in your work, but you kind of need that,” he said.

Not everyone agrees that validation from the traditional art world is necessary for success. Kenneth Reveiz ’12, one of the founders of the People’s Arts Collective, said that “a lot of art spaces can be really alienating, whether it’s because people don’t have the money or because it’s not part of their culture or habit to go to galleries.” According to its website, PAC is a “group of artists and activists collaborating to address social, racial, economic, environmental and human injustices in New Haven.” Reveiz and his cofounders, Diana Ofosu ’12 and Gabriel DeLeon ’14, want to use art-based interventions to address these injustices.

PAC rents two formerly dilapidated storefronts on College Street for $250 a month. All of their events and services, which include a take-what-you-like pile of clothing and books and classes taught by members of the New Haven community, are free. During PAC’s weekday open hours, anyone is welcome to come in and create art–or just hang out.

When I visited PAC to speak with its founders, I did not understand their specific goals; I knew nothing beyond the mission statement. They told me that art-based interventions are highly aesthetic, mostly performative actions that create some change in the world. One tactile example of a solvable problem, Ofosu said, is bathroom signs. The way the signs graphically represent men and women is alienating to those who may not identify with those representations. Ofosu, Reveiz, and DeLeon are searching for gender-fluid graphics–one café in Santa Cruz has a robot graphic on one of its bathroom doors and an alien on the other. The point is to illustrate that choosing of a bathroom should primarily be based on personal preference, Reveiz said. After two brainstorming and planning sessions, they plan to gather a group to replace bathroom signs around New Haven on October 26. “It’s an intervention because it actually exists as a change in urban space,” Ofosu said.

Ofosu and Reveiz both graduated from Yale last May, and DeLeon is a member of the class of 2014, currently taking a semester off to focus on PAC. They have all studied art since coming to New Haven. DeLeon is an actor and Theater Studies major. Reveiz is a poet and playwright. Ofosu majored in History of Art and started creating art of her own during junior year, inspired by Guy Debord’s Society of the Spectacle and its interpretation of ethical representations and how images function under capitalism. The three share a progressive political worldview; Reveiz is a community organizer, and he, Ofosu, and DeLeon became close with members of the Occupy New Haven movement.

They started PAC, Reveiz said, because they wanted to have an independent voice that was not dictated by “some bullshit art world standards, expectations, or definitions of success.” They said they are presenting an alternative way of living, one that “provides resources for people outside dominant modes of capitalism.” By creating a space where anyone can create art, they are empowering members of the New Haven community.

Their Yale education may seem at odds with their radical language. By applying to and attending an Ivy League university, they have already sought out a very traditional measure of success. But they said they all still feel that they are outside the structures of privilege that govern the art world.

“What we look like and who we are is very much not the norm in the art world or who runs any organization,” they said. Ofosu came to Yale intending to major in classics. She found it difficult that her coursework was dominated by the traditional white male canon, and that her perspective as a black woman was not represented. Coming up against what she described as Yale’s “traditional, old boys’ club” taught her that she does not align with that aspect of Yale’s identity and reputation. At the same time, she says she wouldn’t be where she is now without her experience at the university. In fact, it seems unlikely that PAC would exist if the founders had not had access to Yale’s intellectual and institutional resources. Their place in New Haven’s art world is defined on some level by this privilege, and they hope to use it to create an alternative space for creation and expression.

At an event called “Stew and Stencies” in October, the group of attendees was diverse: Yalies, curious passersby on the street, New Haven activists, homeless New Havenites, people who just wanted stew, and people who just wanted to make stencils. PAC passes out flyers in Fair Haven as well as downtown, and hopes to engage and empower members of multiple communities by giving them a space to make art and, ideally, change.

On October 13, “Hard Works” transferred from the DaSilva Gallery to the Afro-American Cultural Center at Yale. Before it closes on November 12, Skinner hopes that some of the art world insiders who did not make it to the DaSilva gallery will come to the show, perhaps drawn in by the Yale-centric location. “I’m really looking forward to being in institutions,” he said. But it is unclear what will come of the exhibition, and whether it will draw the members of the Yale community that Skinner thinks it will. Over the summer, he sold his first three paintings to a private collector, and another during the “Hard Works” reception. But the income generated by those sales is not significant enough to allow him to leave his jobs, and he is still striving for wider recognition.

According to Skinner, it is especially difficult to be an artist in New Haven. The city is much less cosmopolitan than New York and has fewer galleries and art institutions. But when I brought up this idea at Artspace, Culligan disagreed. “In some ways it seems like it’s easier to be an artist in New York, but there’s so much more competition,” he said. “You’re just a drop in the bucket, and New York’s a much bigger bucket.” Kauder said that New Haven’s location between Boston and New York makes it easier for Artspace to tap into the art networks in those cities and bring curators to events like Speed Networking, for which twelve of the art professionals came from other cities.

After the “Speed/Networking/Live!” event, I looked up many of the artists who participated. Some of them had been showing in galleries and even small museums across the country for decades. They have fruitful careers, and yet most are unlikely to become household names.” The more I learned about Artspace and PAC, and about the different interpretations of recognition and success in the art world, the more I wondered whether Skinner was placing too much stock in a big break or the transformative powers of fame.

Shortly after his birthday, Skinner told me, “I’m thirty five years old, and I can’t be a famous artist when I’m dead. I need that recognition now.” As thrilled as he is to be showing at Yale, he still says that he does not know what is going to happen next in his career. “I don’t know how to connect the dots. I don’t know where my break is going to come from.” Skinner’s background itself is not an impediment to fame, but his lack of access to important resources may be keeping him out of the inner circle. His big break may be realizing that the power of his voice need not be defined by the number of people who choose to hear him.