“Opposition? Partner? Speaker?” Matt asks as he stands before the judge, taking stock of the room before he starts his speech. His partner is seated to his right, and his opponents, Zariah Altman and Xavier Sottile, are waiting on the left. He places his cell phone timer on the conference table. “All right, I’ll begin.”

The room is quiet.

“From Russia, to China, to Iran, to Syria, to ISIS, far too long the U.S. has been proven to be weak on the international stage.”

His speech aims high, but its wording comes across as a bit clunky.

“There are numerous actions that you could use to confront aggressively,” he continues, “including but not limited to resuming aerial surveillance flyovers, excluding China from the G20 summit, quotas on treasury buyback programs, and enforcing extradition and environmental treaties as written by the U.N.”

It’s a Saturday afternoon, and we are in a classroom in Yale’s Kline Biology Tower. They’re competing in the parliamentary debate division at the Yale Invitational, an annual tournament hosted by the Yale Debate Association each September. Matt and Jack, two blond boys from a wealthy Long Island public school, are teamed up against Zariah and Xavier, seniors at New Haven public schools who are a part of the New Haven Urban Debate League (UDL).

UDL is a Yale organization that sends undergraduates to New Haven public high schools to teach competitive debate. The league has been around for a decade, but in the last few years it has grown to encompass more than thirty-six Yale student coaches and a hundred New Haven students. UDL students compete against teams from around the state, and recently, have started to hold their own against teenagers from the affluent suburban districts who have traditionally dominated the debate scene.

The stakes are high—this is the fourth round, and Zariah and Xavier think that they won their first three matches. Opponents are assigned based on a win-loss record, and Zariah and Xavier are now up against debaters who are older and more experienced than their previous opponents. If they win this round, they’ll compete in the final rounds tomorrow.

Today’s resolution: “This House would aggressively confront China.” In the world of debate, “resolutions” are the polemical but vaguely worded statements that students argue for or against. The team speaking in favor defines the terms, so the “House” could be the U.S. House of Representatives—or, if the team gets goofy, it could be defined as the ruling dynasty of Mars. These kids, however, are taking it all very seriously.

Today’s resolution: “This House would aggressively confront China.” In the world of debate, “resolutions” are the polemical but vaguely worded statements that students argue for or against. The team speaking in favor defines the terms, so the “House” could be the U.S. House of Representatives—or, if the team gets goofy, it could be defined as the ruling dynasty of Mars. These kids, however, are taking it all very seriously.

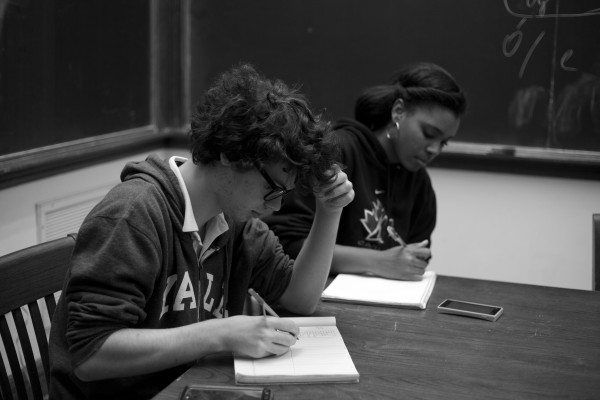

As Matt speaks, his teammate looks down at his notes, which he keeps in a leather portfolio. Zariah and Xavier bend their heads over their legal pads, outlining their opponents’ speeches next to their own hastily scribbled arguments. The sheer volume of information these two boys know—the intricacies of international politics, the minutiae of U.S. foreign policy—doesn’t intimidate Zariah or Xavier. In just a few minutes, they’ll have a chance to knock it all down.

***

Unlike the other urban debate leagues that began to pop up across the country in the 1990s, UDL is unaffiliated with the National Association of Urban Debate Leagues. Run by a team of volunteer Yale students, it operates without the endowment and permanent staff that the national association requires for membership. Instead, Yale’s UDL relies on students’ time and resources from Dwight Hall, the umbrella organization for Yale’s social justice groups.

Aaron Zelinsky ’06 LAW ’10, founder of New Haven’s UDL, got the idea from his great-uncle Seymour Simon, a justice of the Illinois Supreme Court in the 1980s who worked on Chicago’s UDL program. Simon told Zelinsky about the program at a family bar mitzvah, and Zelinsky pitched the idea to Reggie Mayo, who was then the superintendent of the New Haven public schools, in 2004.

The program had trouble getting organized, but it has grown steadily since then. “We got no money from the schools,” Zelinsky says. “The way I sold it was: This is zero cost. That was the only reason we were able to do it.” Only six high school students showed up to the first tournaments, so two Yale students had to step in and debate to even out the numbers. As late as 2011, when Becca Steinberg ’15, the current president of UDL, began coaching students, the league had to occasionally cancel tournaments because not enough kids had signed up.

Last semester, UDL expanded into three new schools, and this semester, into two more. Twelve New Haven public schools are now part of the league, and tournaments haven’t been cancelled for lack of debaters in at least a year. More than that, UDL kids have done well in the last few years at state and national tournaments. At the 2014 Osterweis Debate Tournament, a free event for Connecticut high school students financed by Yale’s Jonathan Edwards College, the top two teams were from UDL. In both 2013 and 2014, the top-ranking junior in the tournament was a UDL debater. The most recent was Zariah.

The demographics of the UDL students are very different from those of the largely white, affluent students who won—or even participated in—these competitions prior to the founding of the New Haven league. At some UDL schools, such as Wilbur Cross, over eighty percent of the students qualify for free or reduced-price lunches, and even at schools with slightly more middle-class students, such as the Sound School, nearly half qualifies. At all but one of the twelve schools in which UDL debates, minority students outnumber white students.

John Buell, a civics teacher at the Sound School who is the faculty advisor for the UDL team, says the kids on the debate team tend to be more academically inclined in the first place. UDL has had champion debaters ranging from the children of Yale professors to kids who are undocumented immigrants, but after six hours at school, they all have to sit down and listen, think hard, and argue. UDL offers students a safe space to work through these intellectual challenges together. “That feeling of insecurity that a lot of these kids can have when they’re suddenly facing wealthy white Connecticut out there in a broader venue—they don’t get that, they’re sort of just amongst themselves,” Buell says. “And the judge is being incredibly supportive in the critiques that they’re giving.”

The idea is not only to train them to debate better, but also to learn to communicate effectively outside the world of debate. Something that Zelinsky says sticks with me: “Not every kid that comes out of the UDL is going to be going to Yale College. And not everyone has to be…if it helps a kid walk into a job interview and be able to present cogent arguments, then he’s learned something useful. If it helps someone feel a little more confident when they’re speaking, that’s useful. [Maybe] you can help some kids who wouldn’t otherwise go to college, or wouldn’t otherwise get a job if they’re not going to go to college.”

In Zelinsky’s terms, “This is giving people a voice. That’s what you’re doing, you’re giving people a voice.”

***

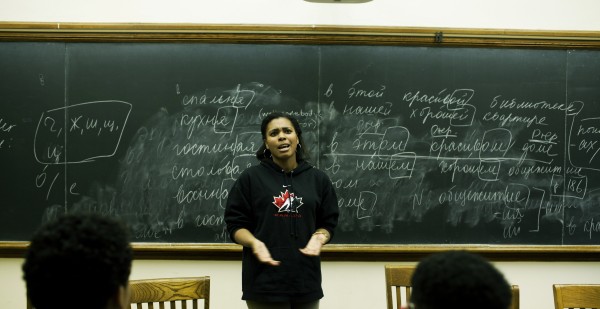

Zariah grew up in Stratford with her mother and grandmother. Her father left when she was 2, and she only occasionally visited the Native American reservation where her father’s family was from. She moved to New Haven in elementary school, and she started competing in UDL when she entered the Sound School as a freshman in 2011. In mid-September, she along with three other teammates, have come to Dwight Hall for their weekly practice. They’re working with Steinberg to prepare for the upcoming Yale Invitational tournament.

“Have you guys heard of soft power versus hard power?” Steinberg says.

“Yes,” Zariah immediately jumps in. “In California, I did.”

Zariah won a half-tuition scholarship to a debate camp at Stanford University last summer because she was the highest-ranking junior at the Osterweis Debate Tournament. She tells me that she didn’t find out till a few weeks ago that her scholarship was only half-tuition: Without telling her, Steinberg held a bake sale to come up with the other half.

She is now waiting to hear whether she will have the chance to attend an elite university, like Stanford, as an undergraduate. In September, she submitted her applications to the Questbridge program, which aims to connect underprivileged, high-achieving high school students with top-ranked schools.

Two of the other debaters, Dhaval and Vishal, have to go home early, so Steinberg has Zariah and Xavier debate alone against one another. This kind of debate is called “Ironman.” After the details are settled and the kids have time to prepare their arguments, Steinberg gets her cell phone out to time the speeches.

Before they begin, she says, strict but smiling, “Now, Zariah, you’re going to talk slowly and loudly, right?” She turns to me and explains. “Ever since Zariah got back from California she’s been talking incredibly fast, which is how they debate there.”

When Zariah begins to speak, I understand Steinberg’s concern. Zariah is authoritative and unapologetic, and she argues very, very fast. She brings indignation to whatever argument she takes up. When she finishes a claim, she says “right,” not as if it’s a question, but as if it’s an affirmation. She holds out her arm, palm outward, for the audience’s (or the judge’s) recognition, or raises her palm outward, like “stop,” to ask them to join in her rejection of the opponent’s argument. She looks the judge in the eye.

***

I’m at the Sound School one afternoon in October, waiting for UDL practice to begin. The kids have trickled in from their classes, chatting and joking with one another. “I love you, Giovanni,” one girl repeatedly calls to her schoolmate. “Love you too, girl,” he says back.

I’m at the Sound School one afternoon in October, waiting for UDL practice to begin. The kids have trickled in from their classes, chatting and joking with one another. “I love you, Giovanni,” one girl repeatedly calls to her schoolmate. “Love you too, girl,” he says back.

The resolution for the day’s trial debate is especially hard. Once the teams have paired up, Steinberg writes the resolution on the board: “THBT American search engine companies should not do business in countries that censor the web.”

“What’s THBT?” a skinny blond kid asks.

“This house believes that,” explains Zariah.

At another table, Steinberg is fielding other questions about the resolution, which the kids don’t quite understand.

“Like, you can’t go on Facebook in China,” Steinberg explains.

“On Facebook?” the girl responds, shocked. “What!”

Meanwhile, Zariah is trying to get her team’s arguments ready. Google is a massive American company, she says, and it would be hypocritical for the American government to promote free speech while allowing American companies to cooperate with censorship laws.

“Does that make sense?” she asks them.

“Yes…” her teammate says hesitantly, playing with his pencil.

“Are you just saying that?” she laughs and explains it again. It isn’t at all condescending: She’s older, and has been debating for a long time. The younger students listen to her.

Most practices go like this. The coaches also have monthly curricula, which attempt to fill in the gaps, teaching students history, philosophy, and civics that their schools haven’t covered. I even learned a new phrase at a practice I attended: “Stare decisis,” to stand by decisions, usually those by previous courts.

On the way back from practice, Steinberg tells me that when Zariah first started debating three years ago, the Sound School team had only two students. The coastal school’s popular rowing team still monopolizes many students’ after-school hours, but the debate team has grown steadily each year.

I ask what Zariah was like back then, when the only other debater was Jake Colavolpe, who is now a freshman at Yale. “She was so bad,” Steinberg laughs, sheepish. “The first time I saw the two of them debate, the topic was, should the New Haven Green have a Christmas tree? And their speeches were, like, forty-five seconds long.” Not filling the allotted time is a sign of a rookie debater, she explains.

How did Zariah get so good? I wonder. Steinberg tells me that once they got a little better, Zariah and Colavolpe would debate against Yalies. The high schoolers would often lose, but they wouldn’t give up: “Every time that happened, they worked five times harder,” Steinberg says.

I think of the sheer number of hours Steinberg has spent with the students she coaches. I meet Colavope on a bench in the center of Yale’s campus to talk. “Undoubtedly, a very big reason why I’m sitting here on this bench is because of them,” says Colavolpe, referring to Steinberg and her fellow coaches. Steinberg tutored him for the SATs, read his college essays, and baked and sold cupcakes to raise money for his trip to a debate camp at Stanford, the same one Zariah attended the following year. “Throughout high school they were just a phone call or a text away if I needed them.” It’s no wonder Zariah sounds like a younger version of Steinberg when she addresses her teammates.

***

At the Yale Invitational, the tournament the kids had been practicing for, nearly a thousand kids in ill-fitting suits are looking for coffee and breakfast. Parents are trying to find where tours of the campus start. Inside the Sloane Physics Lab, parents take awkward iPhone photos of the kids clustered in the auditorium. No New Haven public school student was on the roster until 2012, as far as Steinberg knows. This year, there are four.

It’s easy to pick Zariah out of the crowd—she’s the only black student competing in parliamentary debate. When Steinberg asks Zariah where her suit jacket is, she says, “It seemed really big. I’ll wear it tomorrow.” Her hair is straightened, kept short above her shoulders, and hoop earrings dangle from her ears. She’s talking to her debate partner, Xavier, a pale kid in a navy suit jacket with bright, fake-brass buttons. His black dress shoes remain untied all day.

Steinberg tells me that New Haven UDL tournaments, kept within the New Haven league, are normally held on Friday afternoons so that they don’t interfere with students’ part-time jobs. Today, on a Saturday, some cannot make it to the competition because of work. Still, urban teams from Detroit and New York City join the four UDL debaters present.

The tournament is late to start, so the kids chat for a while. When they start talking about Yale, Vishal says, “The funniest thing I’ve heard Yalies say has to be—this one Yalie on the Green says to the other, in the middle of the Green, ‘Are we in the ghetto yet?’”

Zariah and Xavier also run into a team from UDL’s multi-day summer program, run by Yale students, which draws students from across the state. One of the students is wearing a grey sheath dress, her smooth blond hair tied back in a bun. The girl’s fancy new nude patent leather pumps have given her a blister, and at one point she texts Steinberg, who is helping coordinate the event, to ask if she has a Band-Aid. She tells me that she attends the affluent Greenwich High School and that she’s applying early to Princeton. She has an edge up, because one of her parents went there.

This girl’s background confirms what I’ve heard about debate culture outside UDL. Zelinsky, the founder of UDL, told me, bluntly, “Debate’s a rich kids’ sport.” In some way, Yale Debate Association capitalizes on the market of kids who are willing to fly across the country to compete; the association organizes the Invitational in part to fundraise for their own collegiate competitions. However, at Steinberg’s suggestion, the YDA instituted a policy that allows some students to waive the tournament entry costs, which run $60 to $90 per team.

Xavier starts to flirt with the blonde girl. He asks her what the difference is between Connecticut Debate Association kids and UDL kids. “We’re cooler,” she says, teasing. “What! No,” Xavier replies, “We’re the home team!”

***

“Let me just explain to you what the social contract is,” says Zariah, as she faces Matt and Jack back in the Kline Biology Tower and begins to take apart their argument.

She criticizes their blinkered vision in foreign policy. “So the first point we have is diplomacy,” she begins. “Side Government would have you think that there’s no other option besides flying over China and pissing China off.” Her style is elevated where it has to be, but also to the point.

She tells me at the debate camp she’d attended, they’d taught her four ways to refute an argument. It could be wrong in itself: self-contradictory and invalid. It could be unsound: Its logic is valid, but not all of its premises are true. Or the claim could just be completely irrelevant. Finally, it could fail to be persuasive: An argument can be valid and sound, but insignificant compared to another, stronger argument. “My dream is to refute an argument in all four ways,” Zariah says, laughing. She comes close this time. She and Xavier win the debate round, but they don’t make it to finals. There’s a run-off, and they come out behind. Still, they’ve come a long way.

***

On Friday, October 10, in William L. Harkness Hall, UDL has its first tournament of the season. It’s their largest tournament yet, with seventeen teams competing from nine different schools. It’s here, with students gathered from all over New Haven, that I get a sense of the community of debaters that UDK has built in this city. The students filter into the small auditorium, most in their school clothes, though one or two have put on a suit jacket or a skirt for the occasion.

Zariah greets friends from other schools, some of whom she’s encouraged to join the league. “I pretty much just yell at them until they come,” she says, laughing. She teases a childhood friend of hers, Kyle, who wants to debate her on his first round. Coming from Metropolitan Business Academy, which only started a UDL program last semester, he has never competed before. Tatiana, another friend, jokes, “He’s begging to go against her on his first debate, when everyone else in this room is praying not to get her!”

They do end up teamed up against one another, and at the end of the debate, Zariah smiles widely at Kyle. He looks impressed, if a little shell-shocked. “It was so, so great debating with you,” Zariah says to him, pinching his cheek affectionately.

At the awards ceremony after three rounds, Zariah and Xavier place first in the varsity division, though other students take the award for best speaker. At the end of the evening, the kids eat the pizza UDL has brought for them, and they say their good-byes to the kids from other schools. They won’t see them until the next tournament, in November. It’s dark and chilly outside compared to the halogen lights and central heating of the building. Their parents have pulled up their cars over on Wall Street to pick them up and bring them back from Yale, or they walk with their plastic medals around their necks over to the Green to catch the bus home.

Caroline Durlacher is a senior in Jonathan Edwards College. She is a senior editor of the New Journal.